by Enric Granzotto Llagostera & Rilla Khaled

First published March 2023

Download full article PDF here.

Abstract

Cook Your Way is an alternative controller game about a fictional visa application system in which potential immigrants are asked to prepare typical dishes from their country of origin to show immigration judges they can contribute to their society. Players use a custom cooking station device to cook Brazilian feijoada and its usual accompaniments, answering questions about an applicant’s background. Their performance is evaluated and reported as part of a longer, opaque process.

In this paper, we discuss the creation process of Cook Your Way from the first author’s perspective, starting from the project’s beginnings in 2017. We revisit specific moments, design moves, concerns, and questions with the goal of sharing how themes of immigration, global capitalism, and culture were navigated through game making. Core to this retelling is the first author’s positionality as a white Brazilian migrant PhD candidate in Canada, and his lived experience of operations of racism and whiteness in Brazil and Canada.

The cooking station that forms the centerpiece of this game doubles as a visa application system and employs a fictional version of a variety of border technologies. It remixes aspects of language tests, charters of values, biometrics, and surveillance devices, emphasizing how these technologies work in concert to discriminate against migrants. In short, the cooking station embodies the game’s political critique.

Woven throughout this written account are sketches, photographs, sources, animations, and extracts of the game at different stages of its development. In articulating the sensemaking and reflection process invited through making while constantly circling back to discourses around immigration and global capitalism, we further extend what “a conversation with materials” might look like in the context of game design.

Keywords: immigration, whiteness, reflective game design, alternative controllers, political game design, game design practice

Introduction

Cook Your Way (Enric Granzotto Llagostera, 2018; hereafter CYW) is an alternative controller game about a fictional visa application system in which players take on the role of potential immigrants. Unlike immigration systems we are familiar with, the CYW system depicted requires applicants to prepare typical dishes from their country of origin to convince immigration judges of their capacity and willingness to contribute to their new society. In the current version of the game, players encounter one specific application and must use a custom cooking station device to cook Brazilian feijoada and its usual accompaniments, answering questions about the applicant’s background. The game evaluates their performance and reports back on it as part of a longer, opaque process.

A recurring refrain in our work is pushing the boundaries of how political arguments and reflection can be supported via alternative controller design (Granzotto Llagostera, 2019b; Khaled, 2018), noting that alternative controllers productively destabilize assumptions around power and control literacy (Marcotte, 2018). We are particularly drawn to working with anti-hegemonic strategies and games that break, in a variety of ways, with the reproduction of systems of oppression around games (Fron et al., 2007).

The game was created in an academic context in Canada, as a research-creation project by Enric Granzotto Llagostera within the Reflective Game Design (RGD) research group. It started in September 2017 and its first public showcase was at the altctrlGDC in March 2019, during the Game Developer’s conference in San Francisco, USA. Since then, it has been shown at local events, at an academic conference and as part of the AMAZE 2020 festival, where it was adapted for remote play and received the Explorer award.

In this paper, we present a reflective account of CYW’s creation process from a first-person designerly perspective. We revisit particular moments, concerns, and questions that illuminate how the first author navigated themes of immigration, global capitalism, and culture through the processes, materialities, and transformations of game making. Specifically, we discuss relationships between discourses of whiteness in Brazil and Canada, taking into account the first author’s lived experience as a white Brazilian migrant and PhD candidate in Canada. We articulate how operations of whiteness combine with capitalism to shape immigration systems and the borders they help to enforce. This conversation is interwoven with rich descriptions of the game making process, as every aspect of the final game is essentially shaped by these concerns.

In sharing a close, highly personal account of a game creation process, we contribute a precedent to be leveraged by others with regards to design process articulation (Boling, 2010). Kultima (2018, p. 3) discusses the importance of understanding game design as experienced as well as its conditions of practice. To ground this account, we use documentation materials maintained during the design and development approach, including code uploaded to version control systems, photos, and personal reflection journals, inspired by the design materialization approach proposed by Khaled et al (2018).

We narrate the process in a roughly chronological order, acknowledging that there is always an element of reconstruction at the moment of retelling. We connect reflection and design decisions, highlighting the connections to lived experience, socio-political analysis, and the materiality of building an alternative controller game. We strive to stay close to questions and tensions emerging while designing a game engaged with capitalism, immigration, and borders. The sections below are narrated from the first author’s perspective, connecting his lived experiences and reflections of the creation process along the lines presented above.

Setting my Kitchen Up: Initial Moves

Traces of Canada have infiltrated the São Paulo-based lives of myself and my partner in a profusion of ways: upbeat institutional websites, X-rays, permit application forms, reference letters, urine tests, language tests and courses, certified translations and copies, methodical planning, online friends and acquaintances, reading up on a “Brasileiros em Montréal” Facebook group, a yard sale… By the time I begin my PhD, it feels like I have been here much longer.

When I join the RGD group in September 2017, I already know that I want to make games about systems of oppression, as well as the ideologies and discourses that justify and present them as neutral. My mind swims with recent events of Brazilian politics: the judicial prosecution of Lula, the coup against Dilma Roussef and the austerity of Michel Temer’s government. In my design journal I sketch ideas for weighing scale devices that willingly and autonomously tip themselves.

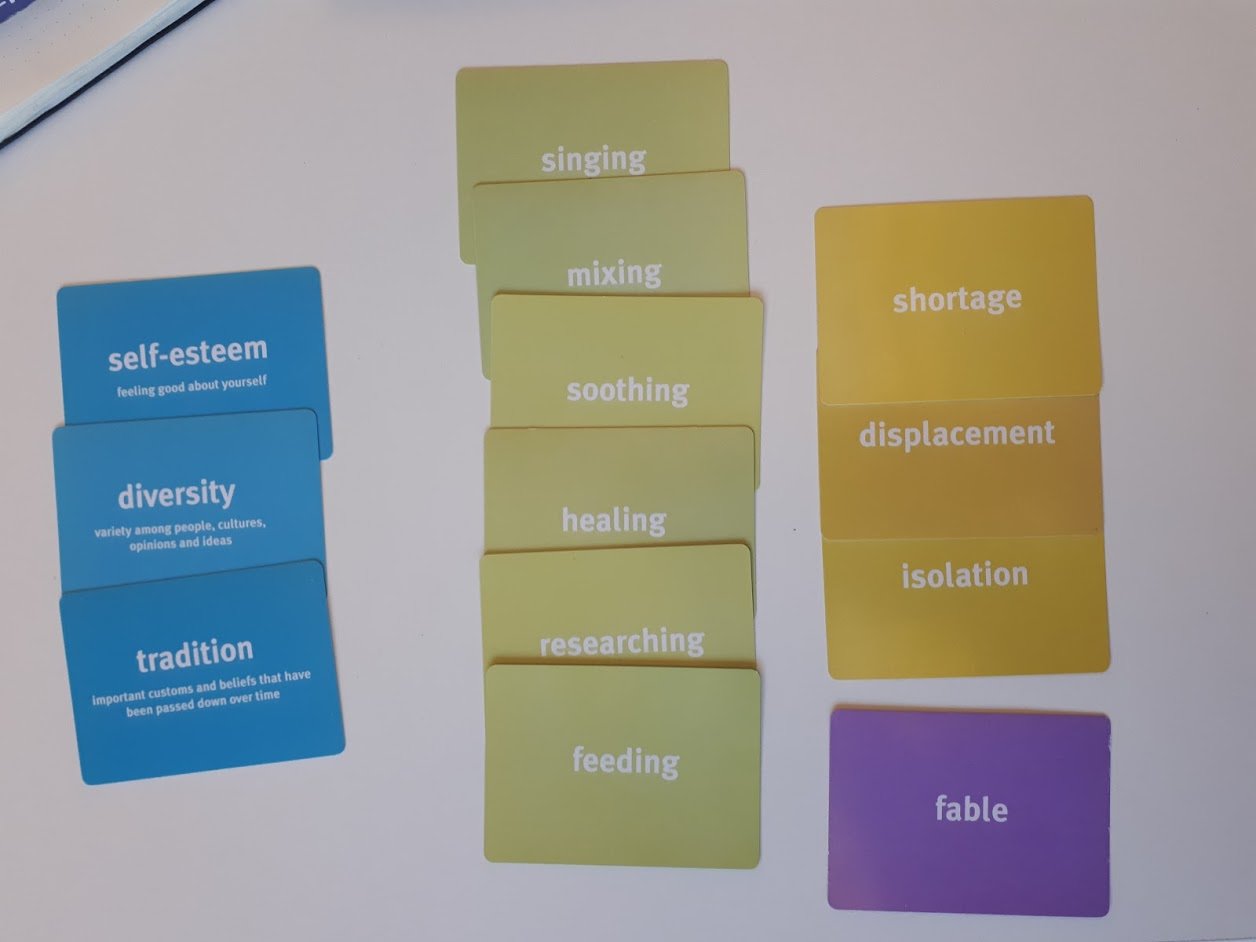

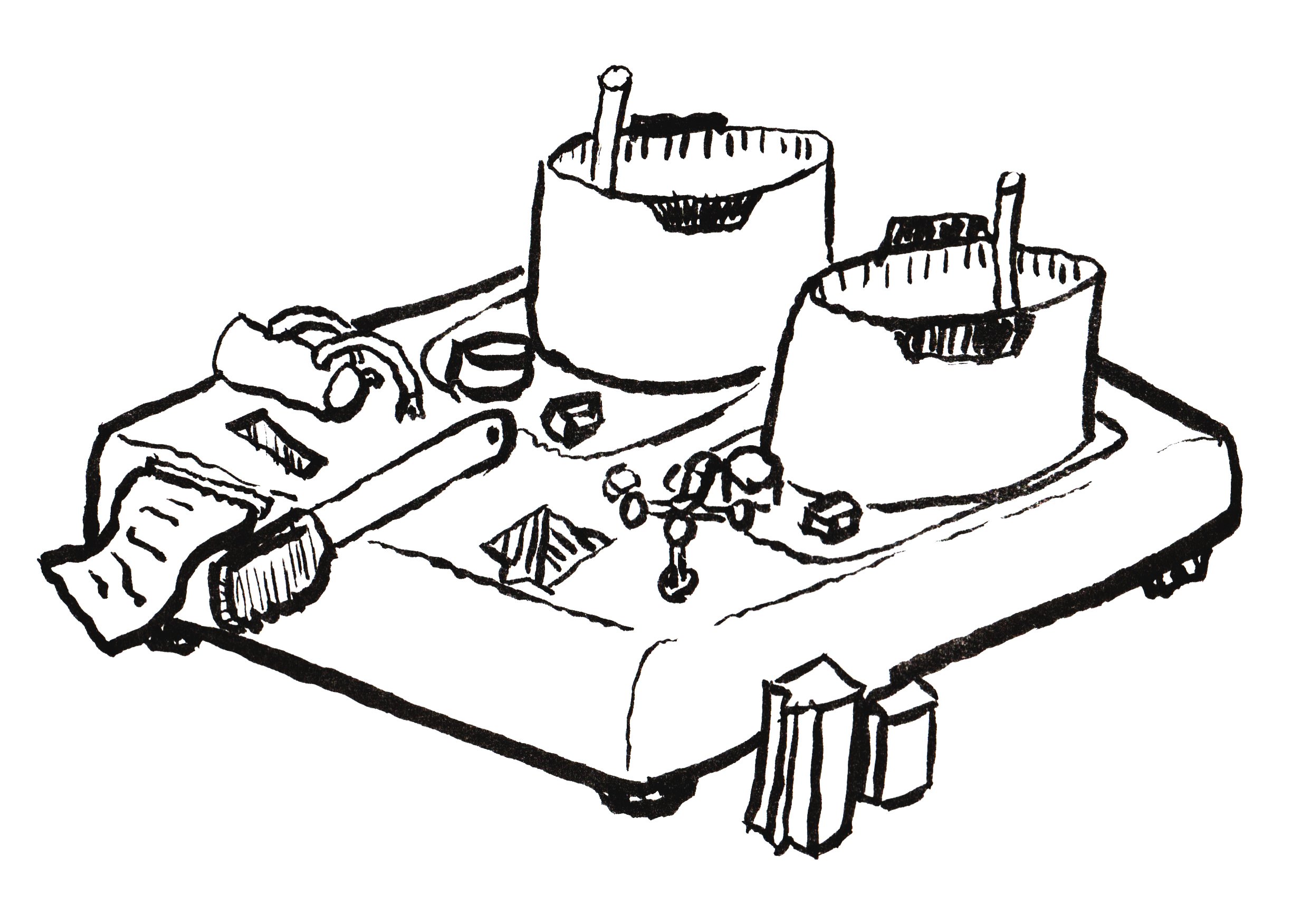

I start experimenting with my peer Dietrich Squinkifer’s copy of a Grow-A-Game deck (Belman et al., 2011), and a particular draw of prompt cards resonates with me. It looks like this:

I am reminded of previous experiences of preparing and eating Brazilian food as a migrant; how it helped me feel connected to family and friends; how it helped me navigate emigration and immigration. These experiences are from my time as an international student in Denmark, and I relive and anticipate them in Canada. Certain notions evoked by the cards stand out: displacement, isolation, mixing, and (particular forms of) diversity.

I explore other notions from the prompts. Riffing on tradition and adaptation, I consider the quixotic search for “authentic” ingredients, the new recipes that emerge from changing tastes and conditions, and the experience of learning about, preparing and sharing food within a migrant community.

I list different metaphors for the act of food preparation, and I research stories about food and immigration. I am increasingly more adept at parsing the language associated with food and immigration: “ethnic foods”, heritage, foodways. Here and there I run into writing on immigrant foods that reaffirms tropes of the exotic and the authentic, an essentialized difference of the Other.

In this period, my ways of framing cooking become more complex.

At this point it dawns on me that my views on cooking are somewhat romanticized. Whereas my initial impetus had been to focus on the caring and sustaining aspects of cooking and the role it has had in my personal history, the next set of ideas I write down present immigration-related tensions and systems as external pressures affecting game actions. For instance, learning a traditional recipe from an older relative while avoiding showing that you are adapting it to your friends’ expectations of your ethnic cuisine. These tentative ideas focus on processes like teaching and learning of recipes between generations in different contexts and with varied life stories, as well as having to negotiate adaptations based on new needs or limitations.

“The more immigrants, the better the food”

I stumble upon a 2017 magazine article titled “The Sriracha Argument for Immigration” (Sax, 2017). In it, the author aims to build a positive case for immigration in North America, against the backdrop of an increasingly anti-immigration Trumpian climate. The argument states that “the more immigrants, the better the food” and that immigrants’ foodways are as compelling a positive argument for immigration as their overall cultural, economic and innovation contributions (ibid). It also includes a short retelling of the “good immigrant” trope as successful entrepreneur, reiterating the “American dream” narrative of class mobility and achievement in capitalism.

As pro-immigration arguments go, this one rubs me the wrong way. The article centralizes the satisfaction of nationals and deems immigration to be positive when it serves their needs in terms of consumption or productivity. The article echoes the logic of points and merit-based immigration systems, but has little to say about the conditions, rights, and political struggles of immigrants beyond the moment in which their labor is enjoyed by nationals. Immigrants are only as good as their contribution.

Ahmed observes that immigrant and ethnic foods are a form of difference that can be consumed, that can be incorporated and assimilated into both the individual and the multicultural national body (Ahmed, 2000, p. 117). The difference of the Other is fixed and essentialized, while the consumer of commodified ethnicity chooses to become different, adopting a style (ibid). Sax’s (2017, n.p.) wish to defend immigration as necessary for “adventurous taste buds” to happen is exemplar of hooks’ (2006) argument concerning the role of white desire for the Other as in politics of racial domination:

The commodification of Otherness has been so successful because it is offered as a new delight, more intense, more satisfying than normal ways of doing and feeling. Within commodity culture, ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture. (p. 366)

I work my reaction to Sax’s article into a game concept. I want to criticize similar arguments about immigration that center the consumption and satisfaction of hegemonic whiteness, the dominant and normative formation that sees itself as neutral or unmarked while perpetuating racial hierarchies and their own power position (Gray, 2014, pp. 8-10). Part of engaging with this critique, as I reflect and design around it, is also navigating my own position as a white Brazilian migrant and my racial status within the overlapping racial hierarchies of both Brazil and Canada. This involves a process of understanding and questioning whiteness in its varying and shifting degrees of privilege and marginalization (ibid, p. 10) in my experience as white migrant and as Brazilian national, non-hegemonic and hegemonic whiteness in Canadian multiculturalism, and the complexity of ways in which ethnicity, race, and class are enmeshed in the Canadian context.

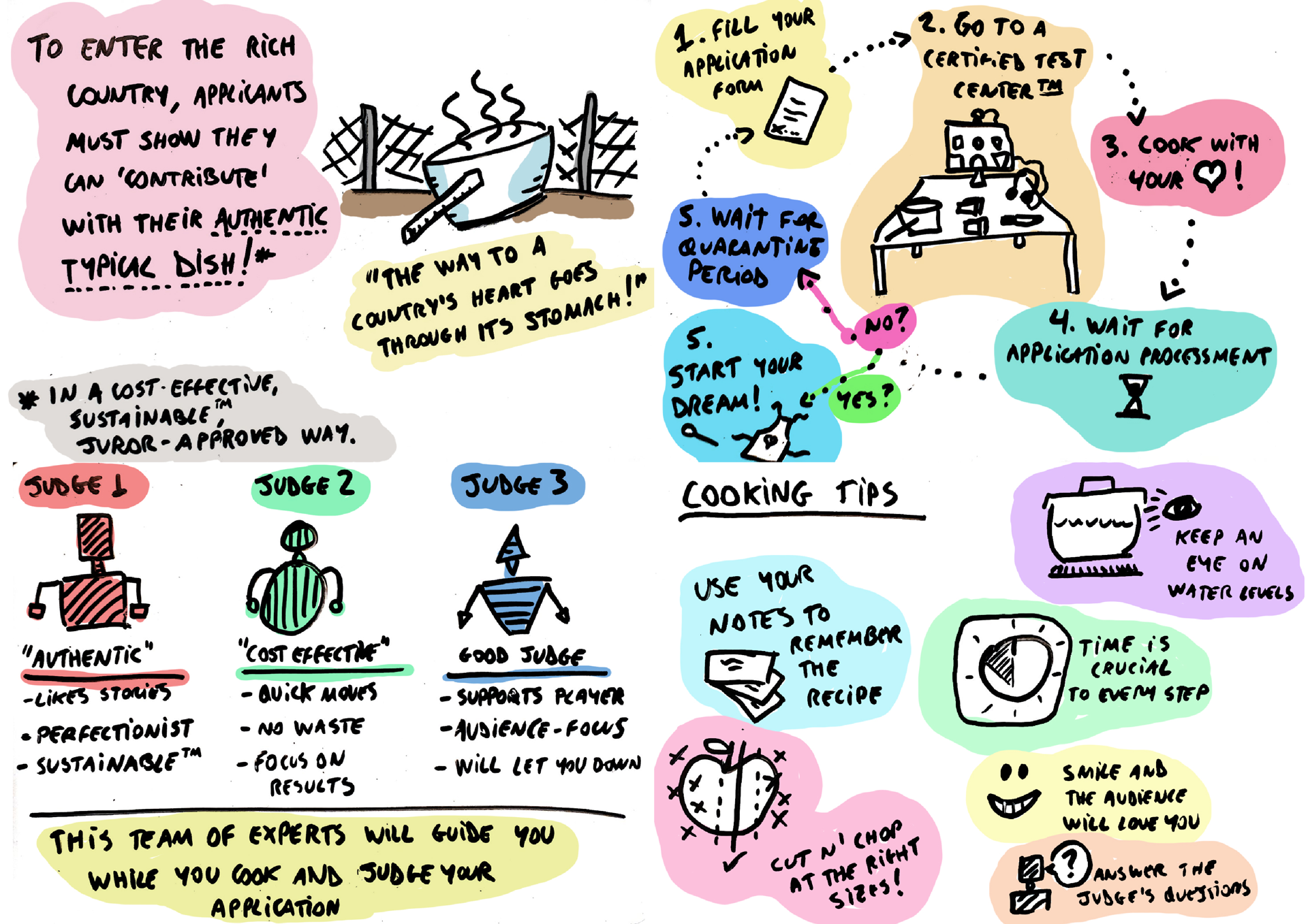

I start sketching a game around food and foodways, trying to work through a kind of enacted and embodied materialization of this critique of consumption and commodification, connecting it explicitly to immigration systems. I imagine players navigating a standardized immigration test to see if they make a compelling enough (in the eyes of the authorities) feijoada to be accepted into a country. The judges espouse meritocratic discourse while evaluating the player, acting as jurors and chefs of TV cooking shows, naturalized experts. I sketch the main aspects of this first version of the idea.

Writing a Strange Cookbook

I focus on the cooking test idea and my thoughts move to how to structure that system. I list recipe steps for the main dish and side dishes that make up a Brazilian feijoada completa to help me think about how to make recipes playable. Which steps should I reproduce faithfully, and which should I abstract? If this is indeed a standardized test interface that could be customized for dishes from a variety of countries, what elements ought to be there?

Starting from recipes seems fitting. The ways in which recipes process and disseminate knowledge about food shape how it is negotiated and contextualized, particularly in the context of immigrant and ethnic cuisines (Gvion, 2009). An issue here is how structural whiteness deploys the idea of “ethnic food” as a shorthand for an otherness ready for consumption. “Ethnic” becomes a marker of the foreign or the Other contrasted to the “national food” and recipes. The “national food”, in a similar definition-by-denial as that present in white descriptions of whiteness (Gray, 2014, p. 8), remains unmarked, a supposedly neutral and generalized mainstream. I wonder how this playable version of feijoada will negotiate this tension, if I should aim for it to feel “authentic”, or if the adaptations can be more explicit and pointing to the question of consumption. After all, the game is, similarly to a cookbook, taking a snapshot of a version of the dish and stabilizing it into a particular structure.

Recipes encode sets of actions: they are a technology for choreographing gestures, checks, and information, producing specific value (van Ryn, 2013, pp. 2–3). In breaking down a feijoada recipe within this imagined test context, the recipe as notation also becomes a set of evaluation criteria or a fitness function; a model against which the cook’s performance can be judged. The ingredients and the completion of tasks are signals that flow through a system, being transformed and likewise transforming other flows of information. This is a cybernetic approach to game design, one that is based on a particular gestural economy of timely and correct movements (ibid). Players are formatted by what the interface mediates and what the machine expects of them as users: “at the interface, not only do players take control over a game, but a game also takes control over its players.” (Pias, 2011, p. 166). Paradoxically, in seeking to make actions of players timely and correct, the felt experience of cooking becomes ever more distant and estranged.

I focus my initial prototyping on digital on-screen elements and how different recipe steps pop up in sequence. I do not have the controller yet, as I am still figuring out what it will need to include. Because I need a placeholder method to interact with my prototypes, I adopt keyboard-based controls, but soon I want to experiment with different motions and gestures. I implement a musical instrument digital interface (MIDI) system that can map game actions to MIDI controller inputs, which I will continue to use until the cooking station is functional. This temporary arrangement feels unsettling and fun to me: the musical instrument interface should let me do more expressive things than the bite-sized fixed steps of the recipe in the game system.

An Incomplete Feijoada Completa

As I develop the different scenes in the game, I narrow down my choices of recipes to include. A possible direction here would be to include recipes from different countries of origin, but I decide to focus on a Brazilian feijoada. I do so to draw on familiarity but also to speak of its complexity in ways grounded in my lived experience and cultural context. Even if CYW gestures at a wider system, I want to ground my recipe within what I know. I still include elements in the game that hint towards a wider deployment of the CYW system for applicants of different nationalities. For instance, the names of dishes of different countries flash in quick glitch-like succession in a waiting screen as the system progresses after the identification procedure. However, the dish that shapes my creation process is the Brazilian feijoada completa.

The feijoada completa is considered the Brazilian national dish, one that represents a Brazilian identity and condenses it into a typical dish (Fry, 1982; Maciel, 2004). It is indeed very popular, eaten and cherished by many Brazilians. It is strongly associated with Afro-Brazilian culture, history and political affirmation. The incorporation and deployment of feijoada completa as a national symbol of Brazil during the 20th century has a complex history (Fajans, 2012; Maciel, 2004). The mainstream deployment of feijoada completa has been held up as evidence of Brazil’s supposed “racial democracy”. This notion presents Brazilian society as tolerant and non-racist (Kamel, 2007), the result of a supposedly “milder” colonization and slavery, marked by racial mixing processes which would show its “minimal prejudice” (Freyre, 2013). This is a false perception that denies the reality of contemporary Brazil’s deeply prevalent racism, and which downplays its history of slavery, sexual violence and genocide (Jacino, 2017; Nascimento, 1978).

As I research the tensions in the process of feijoada becoming a national symbol, I observe parallels between Brazil’s racial democracy discourse and how official Canadian multiculturalism discourses operate. Both Brazil and Canada have attempted to overcome racism by displacing and perceiving it as something in the past (Aparecida Silva Bento, 2002; Thobani, 2007), thus alleviating pressure on whites to face how they benefit from racism in the present. Racism is downplayed as a matter of “backward elements” of society (Thobani, 2007) and confined to individualized actions and attitudes (Arat-Koç, 2014, p. 318). In contrast, contemporary hegemonic whiteness is presented as tolerant, allowing whites to inclusively accept racialized others but only on particular terms: a kind of commodification and consumption that serves to enrich the nation and increase cosmopolitanism (Ahmed, 2000). While I cannot know that the in-game feijoada will evoke all these arguments in the game context, I feel the significance of these resonances.

Even beyond its national symbolic value, feijoada completa is complex. It involves multiple preparation steps, a variety of ingredients, and attention to multiple actions (stirring, skimming, boiling). Its main stew of beans is accompanied by a variety of side dishes and ingredients that differ by region. It is demanding to cook, involving significant time — usually around two days — and labor. It is most often prepared in large quantities and is symbolically associated with celebrations, events, commensality, and affirmation of the continuing history of Afro-Brazilian resistance and cultural traditions (Dias de Souza, 2017; Souza, 2016). But in the context of Brazilian middle- and upper-class society, the labor behind feijoada is frequently offloaded to domestic and food service workers, often Afro-Brazilian, who are poorly compensated and denied commensality (cf. Fajans, 2012). Each feijoada, in its context of preparation and consumption, is entangled in these tensions.

In CYW, the symbolic and cultural complexity and multiplicity of feijoada completa is simplified, flattened, and lost. As the feijoada in the game is shaped into a commodified format meant for the internationalized consumption of the immigration agents, the dish changes. Feijoada is presented piecemeal to the applicant as a dish divided into discrete, simple, and quick steps. It is decontextualized, taken at surface level, smoothed over, operationalized. In that process, the tensions and complexity of Brazilian-ness present in an actual feijoada are paved over. Through abstraction, feijoada becomes homogenized, dehistoricized and processed into a potentially “authentic” dish ready to add “spice” to the hegemonic white culture (hooks, 2006, p. 373). The discrepancy between the feijoadas’ richness of gesture and knowledge and the game system’s understanding of cooking is meaningful as it traces the commodification of Otherness and labor. The cooking in CYW is a measure of individual merit and performance, distanced from any symbolic or shared meaning that a feijoada can have.

Dish Scoring and Meritocracy in Immigration Discourse

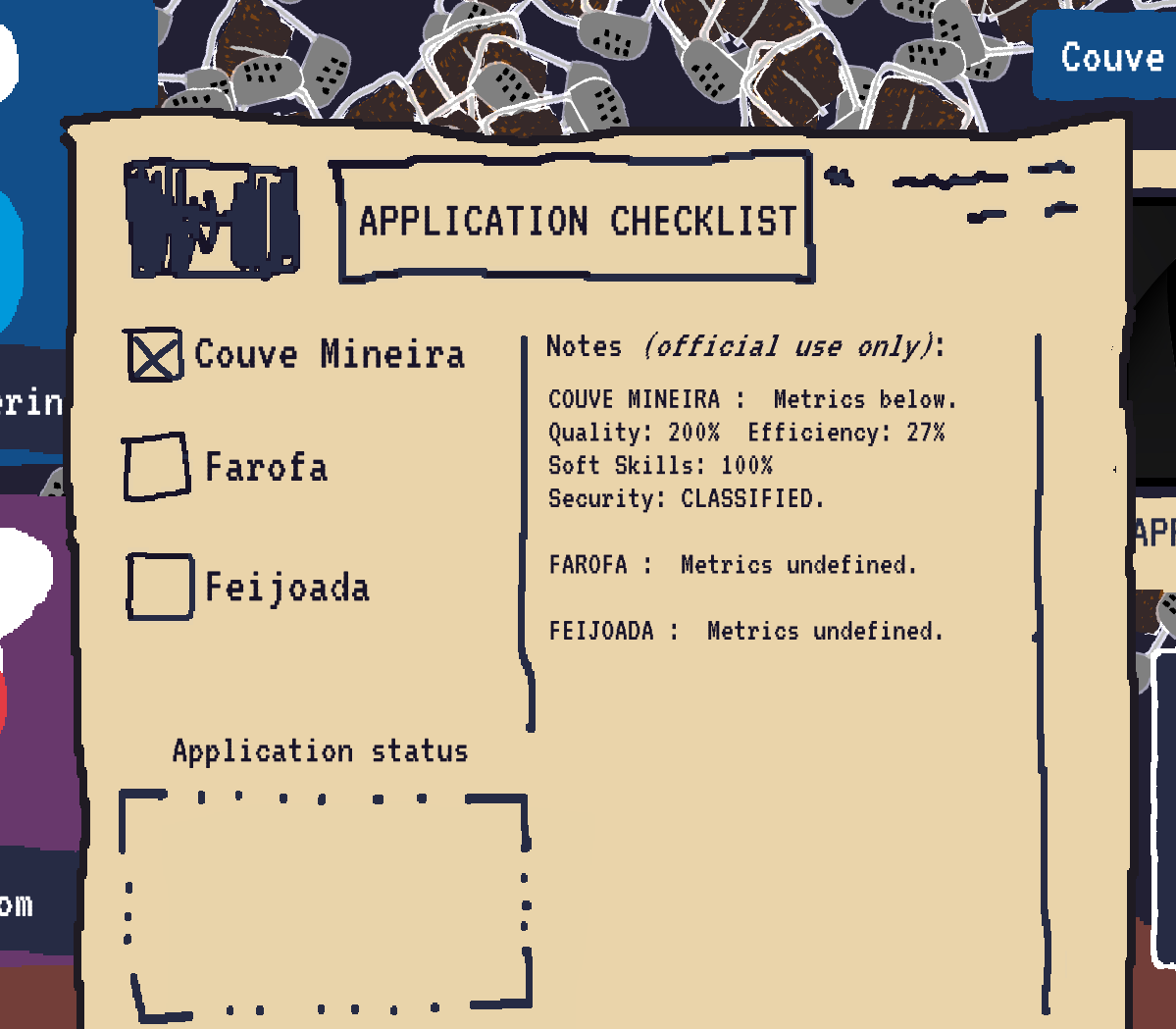

As I program and write the different cooking actions and recipe steps, I consider how to track ingredients, timing, and heat. I experiment with different variables and the ones I settle on refer to precision (whether correct amounts of ingredients have been added), quality (whether the ingredients have been sufficiently cooked), and efficiency (time taken to complete the recipe). These productivity variables, together with opaque and occasional mentions to “soft skills” and “security” criteria, constitute the timeliness and correctness of players while navigating the judges’ instructions.

At the end of a dish-form, players see a checklist of “validated” data and next steps. I consult checklists from Canadian immigration forms to inform my own layout, and it leads me to include a sketchy flag in my own design. The qualities listed have little to do with the food’s taste or texture or symbolic meanings. The record does not read like a dish’s critique, but a work performance review.

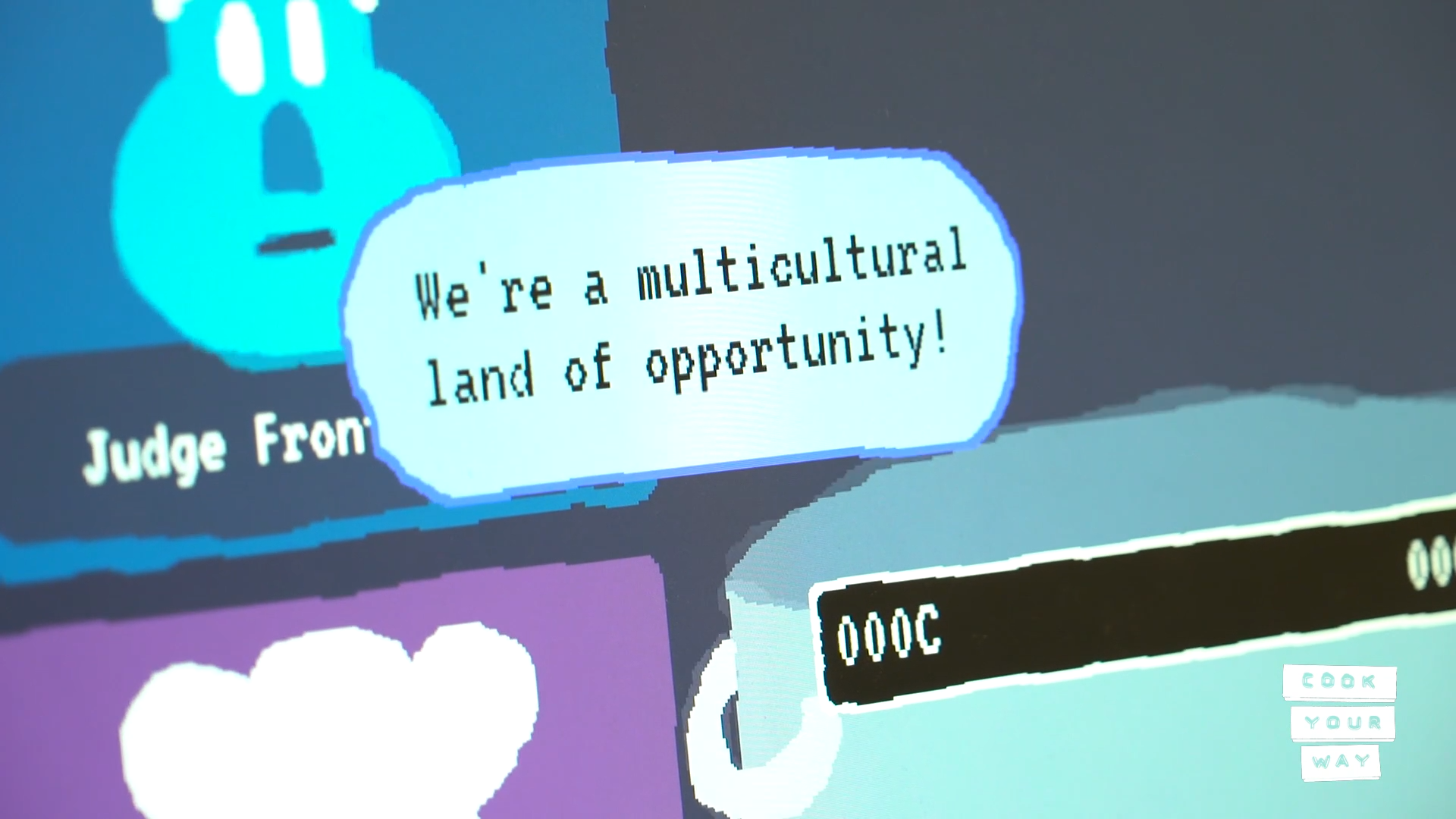

During the checklist sequence and on occasion during a dish preparation sequence, the immigration judges comment on the application progress so far. I include in their dialogue remarks on how the applicant has potential or has been or should be fast-tracked. As I research the Canadian immigration system, its history, and the enshrining of multiculturalism as state policy, I reflect in their lines the meritocratic view that immigration processes concern earning your position in the host society.

Meritocratic immigration systems are characterized by point systems and productivity-centered policy: immigrants are commodified in terms of their market fit, and specifically in terms of their labor power (Arat-Koç, 1999, p. 36). Such valuations become a basis for differential inclusion, for hierarchization and division of immigrants into desirable and undesirable, deserving and undeserving.

When the judges speak highly of the player, they do so in ways that affirm the narrative of the ‘good’ immigrant who does everything ‘the right way’, speaks the official languages, assimilates, leverages culture as cosmopolitanism, has higher wages, legal status and has the mobility and social capital to circulate in transnational markets (Arat-Koç, 2014). This narrative works to justify inequality and marginalization of migrants as fruits of personal responsibility, downplaying systemic implications. It obscures, for instance, the racialized effects of immigrant poverty (Shields et al, 2012) and how Canadian immigration policies, while non-racist in their formulation, leave intact the effects of racism in society and in the international system (Arat-Koç 1999, p. 41).

I reflect on these intersections – how they connect to my personal experiences and the concerns they reveal during the game creation process. As a middle-class white Brazilian international student, I recognize privileges of class and whiteness in my experience, while also navigating how the latter is non-hegemonic and entangled with the racialization of Latin Americans within Canada’s racial hierarchies. I connect the effects of immigration meritocracy with how meritocracy discourses in the Brazilian context justify and naturalize racial hierarchies that privilege whites. Like many other manifestations of whiteness, it does so covertly (Sovik, 2009; Aparecida Silva Bento, 2002). I see firsthand how immigrant communities can themselves reproduce such narratives of meritocratic immigration, when some middle-class Brazilian acquaintances with legal status criticize undocumented Brazilians (1). I also reflect on how meritocratic ideals baked into academic funding and institutional operations ignore the context of international students, while simultaneously limiting their access to key rights and resources on the grounds of immigration status.

As I grapple with these complex interconnections of meritocracy during my design process, I try to clearly state my specific position as well as that from which the game is made, and to trace it in that messiness. I want to convey that the experience the game foregrounds is neither universal nor encompassing; it is not an immigration simulator. The game draws on my experiences and yet it is not even about me, but the systems we find ourselves at the mercy of, the endpoints of larger structures in action.

Under the Eye of the Nation: The Applicant Identification Process and Intermissions

As I progress with digital prototyping, I add a webcam to the game’s setup. It neither records players nor does it maintain records. Its presence, however, reinforces an emergent design strategy of bringing together different processes and metaphors. At one level, it opens opportunities for playfulness and performance, with some players using it for humor and for commenting on what is going on in the application. At another level, the webcam reflects back at me the all too familiar experience of language test centers, visa interviews, and automated border stations from airports. In the game, the webcam works as a mirror usually in the corner of the screen, keeping players aware of themselves and of the implied others surveilling them as they take the test. I want players to be constantly reminded of surveillance, in fact it is one of the multiple systems that make up the in-game assessment.

The webcam takes center-screen status in key game moments. One such instance concerns breaks between dish preparation. In the RGD group, we have discussed how breaks or moments of downtime in a game can support reflection and enable the taking of distanced perspectives. I work breaks directly into the game’s narrative, using the downtime between the preparation of dishes as opportunities for interviews with judges. I find myself, however, subverting the notion of downtime. While the judges present the interview as a chance to detune, the open-ended questions — adapted from immigration forms — are stressful to answer and not enough time is given to respond to them. I also intentionally create ambiguity here. Players are told beforehand that this game is based on my experiences, and that they play as applicant #40048477, but there is not much information to guide how players should respond to the interview questions. Who exactly is the applicant? Is it me, Enric? Or is it players’ ideas of an unspecified Brazilian immigrant? Is it themselves? Or themselves in the role of immigrant? Deciding how to react in this semi confessional moment is difficult, particularly in the public settings where the game is usually shown.

The camera also takes center stage during the “identification procedure” scene at the start of the game, in which a (fictional) facial recognition and body tracking system is activated to locate the applicant’s data, no. 40048477. There is a slightly offbeat pace to the actions required for compliance, which include the raised hands choreography of airport security. In the game, the system always achieves its goal, retrieving information, and the game continues. Facial recognition systems have been designed and deployed as part of a longer history of racist surveillance, encompassing photography, cinema (Dyer, 2006) and other forms of technical imaging, reproducing racist policy and structural systems of racist discrimination (Benjamin, 2019). The fictional functioning in the game, however, does not account for or suggests more explicit reflection about the ways a hyper-visibility to power is deployed along racialized lines and its connections to, for instance, anti-Black policing and carceral regimes (ibid, p.185). The in-game scene focuses on the specific visibility to power produced by such recognition systems in instances of borders and immigration systems, but I believe it should also engage more deeply with their racist dimension.

[Self-testing an early version of the identification procedure scene and its instructions. 2017-12-12.]

As stated previously, though the game does not actually record or track data, the fictional biometrics system activates a code of discipline and serves as an image of state power. Discourses around biometrics and immigration at the state level are deeply ideological and racist; an ominous muddle of justifications based in technical and security arguments (Benjamin, 2019; Nakamura, 2009). In the game, just like rhetoric related to unsuccessful assimilation of immigrants (Arat-Koc, 1999; Thobani, 2007; Walia et al., 2021), security and productivity are aligned, and later questions asked by the immigration judges reinforce this association.

The Test Kitchen and Dropped Experiments

Throughout the process I experiment with different design ideas, not all of which make it to the finished game. I discuss certain abandoned ideas here, as the reasoning process leading to their abandonment is illustrative of how CYW embodies particular arguments.

Role of the Game’s Audience Between Social Media and Choir

In November 2017, I list ideas of quiz moments where the audience interacts directly with the game, assuming a function like the choir in a Brechtian play or a more participative forum-theater-like process (Boal, 2008; Brecht, 2005; Pötzsch, 2017). Another possibility I consider is a reaction system that appears during interview moments, where onscreen emoji convey audience reactions to the applicant’s answers, hinting at the connection between social media feeds and the performativity of social roles.

I drop both ideas because I decide to focus on the experience of one individual as they encounter the in-game immigration system. Such a system focuses on an individual, and the collectives that potentially surround them are not of interest as long as they pose no threat. The application is individual and confidential, after all, as my Canadian immigration forms often remind me.

Thus, the role of the audience becomes an indirect one. The game neither senses nor reacts to audience actions. Any audience is extra-diegetic, serving to hyperrealize the player with their situation of play, making the requests of speaking during interview moments more difficult to perform.

Debug Panel and In-Game Pushback

I consider including a semi-hidden feature in the cooking station: a “debug” panel that exposes management functionality. If a player discovers this back panel during play, they can see on-screen information about the ongoing evaluation of their actions. This report includes classified security-related information, as well as a reboot button. Neither the panel nor the extra information enable the possibility of changing the game’s narrative or end states, but they offer a different frame and perspective of the system.

My idea here is not to present a mode of in-game resistance: I do not wish to design a predetermined, diegetic valve for political subversion. Forms of player opposition to the in-game immigration system do remain available: these include transgressive play, which “occurs when players deliberately violate the structures framing play” (Back et al., 2017, p. 11) as well as the post-play debrief conversation (explained in more detail below) or commenting with others as they play. While the debug panel might on first appearances seem like a backdoor hacking opportunity, its ineffectiveness would be a reminder of the limit of individual resistance when decoupled from larger organizing.

But the debug panel does partly open the black box of the device. Within the game world, what other actors would be able to act or engage with the presented immigration system, beyond the applicant and the judges? And how would these actors translate to real-world systems of borders?

In the end, I drop this feature. I suspect this extra layer of system depth adds little to the game’s message. Finding a potential backdoor into the system only for it to be ineffective might be distracting. It also creates the impression of game design as totalizing; as if the game creator’s role was to anticipate all forms of exploration by players. I think it might communicate a misleadingly over-simplified and cathartic idea of individualized resistance, as if a pre-described loophole would let a person bypass this system, disregarding its collective and structural scale. I keep the debug panel in the physical build as a vestigial feature: the reboot button turns out to be useful when exhibiting the game.

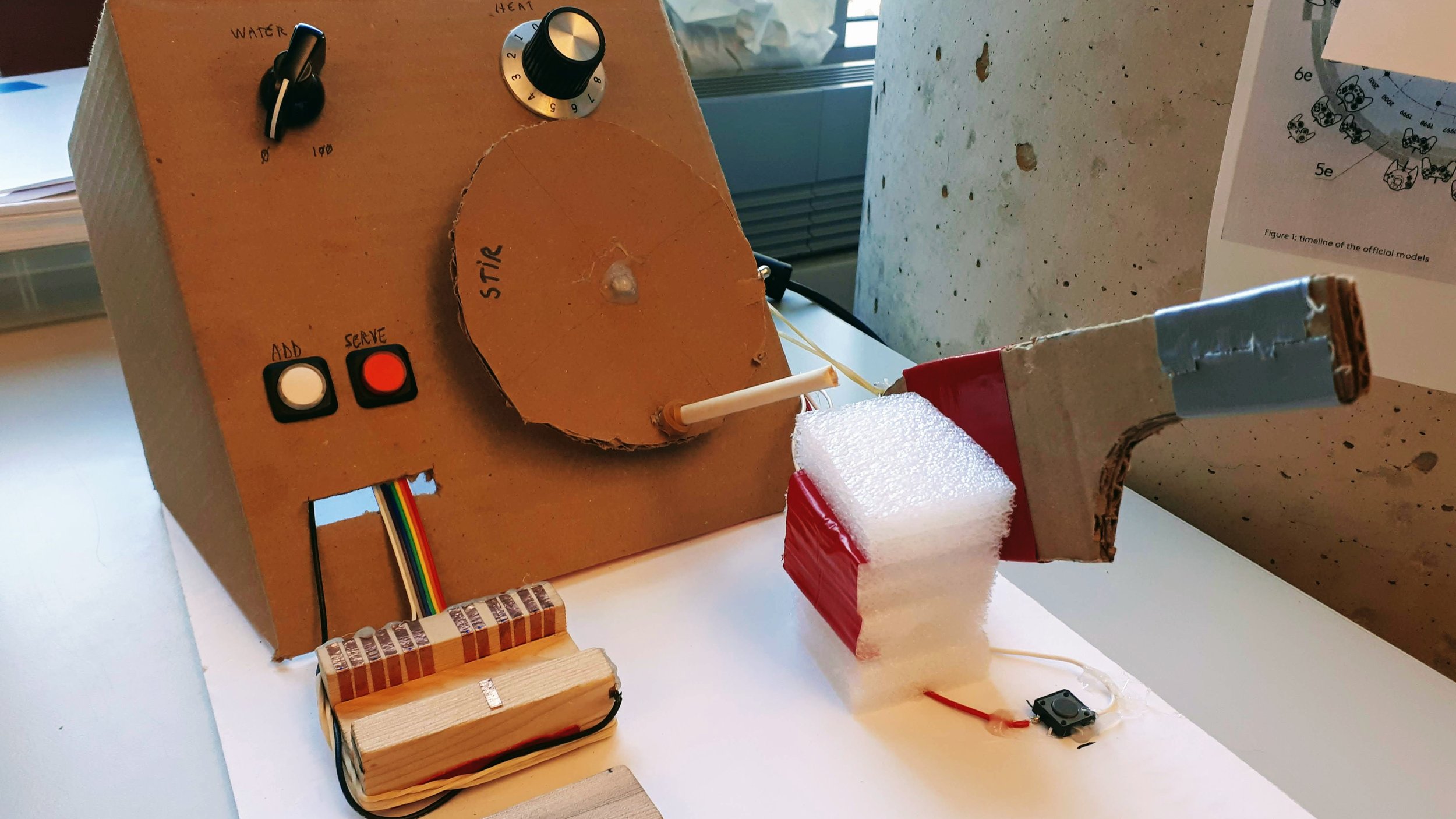

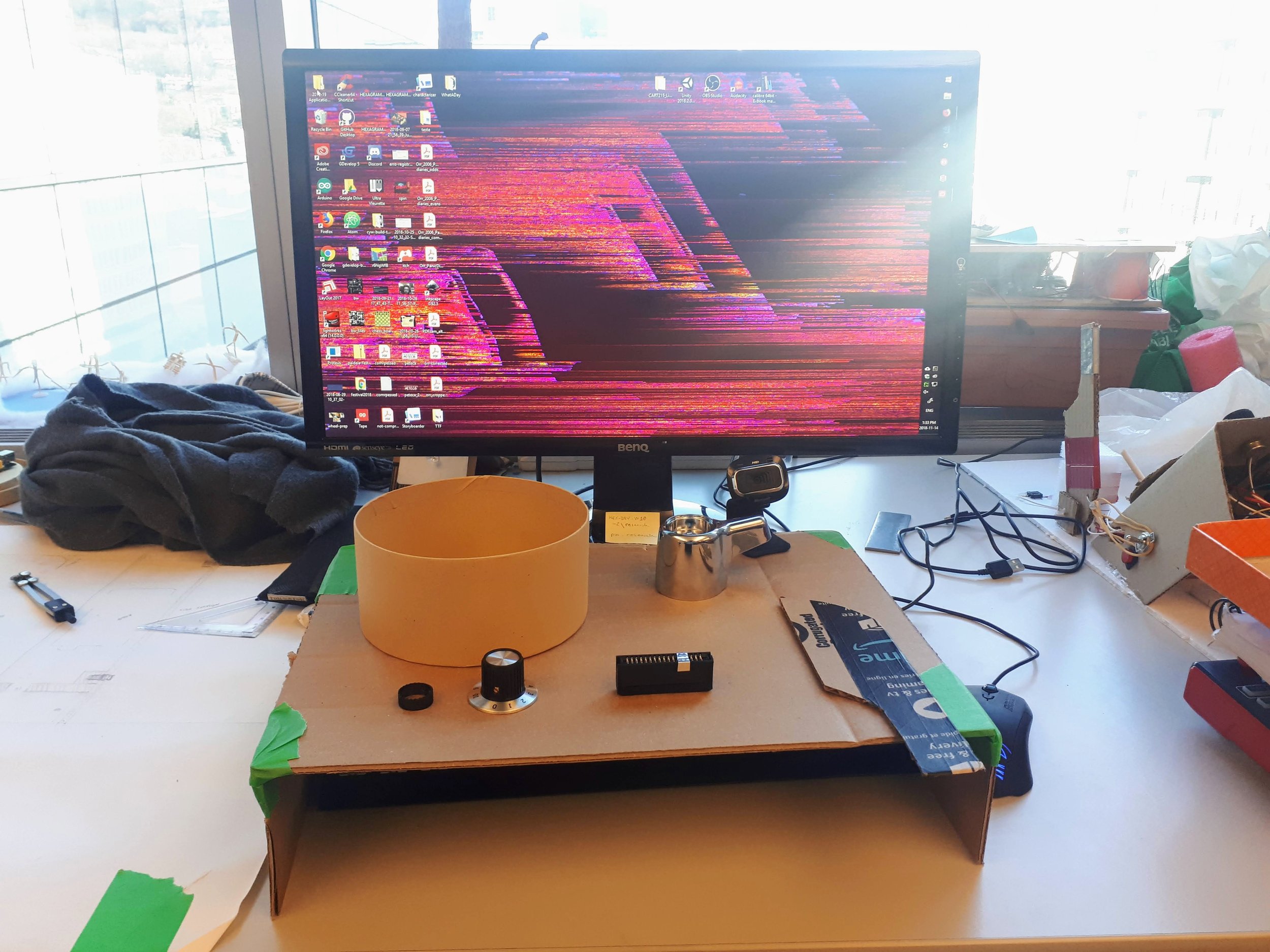

Constructing the Cooking Station

As the work on the digital prototype advances and I am able to play a whole dish, I define the game setup and custom controller in more detail, with the goal of setting a particular stage for play. I start from the notion that game interfaces are less a specific device or thing, but processes of translation and mediation (Galloway, 2012), effects of specific environments made of objects and the relationships between them (Ash, 2015). As players engage with them, there is a coming together which makes play possible (Keogh, 2018). In this process, I stay close to my first sketch of the game idea: an everyday office-like space, a desk, a monitor, headphones, a webcam, wires interconnecting them. Even as I am designing an alternative controller game, it remains close to a conventional videogame (and desk work) arrangement, a “standard loop” of interaction of computing, rendering and input devices neatly divided (Vilela dos Santos, 2018), with the cooking station at its center.

The presentation of the arrangement evokes a variety of activities and settings: language test centers, cooking equipment or toys, office work, even sci-fi computers (more on this later). I plan for these multiple references to evoke tension in their juxtapositions: collisions of dullness and shine, metallic and organic, serious and playful. I want to make the encounter with the cooking station both familiar and strange, and to raise questions about how control and work are presented.

Part of the rationale for blending references to everyday life (office-like materiality), standardization (abstraction and uniformity), and surveillance is to point to how the system in the game is larger than the one instance presented at this cooking station and this individual visa application. The application itself is one node, and the cooking station is one terminal of a system. This multiplicity is an intentional connection to the multiple sites, techniques and devices of immigration systems and borders, how they establish points of control and processes of hierarchization and stratification (Mezzadra & Neilson, 2013).

I design the controller to be based around discrete gestures and serve specific recipes. As mentioned earlier, these must be timely and correct, in exact accordance with the judge’s wishes. As Thobani (2007) notes, Canadian multiculturalism requires migrants to constitute themselves through what is expected of them by nationals, to see themselves through the eyes of the nation, and to preserve particular forms of difference based on such expectations. I experiment with mirroring some of this attention through in-game action: ingredients, cooking, culture, work, all of these are emphasized through the ways that the in-game system notices the applicant and exercises a loop of control, putting players ‘on the spot and on duty’ (Pias, 2011).

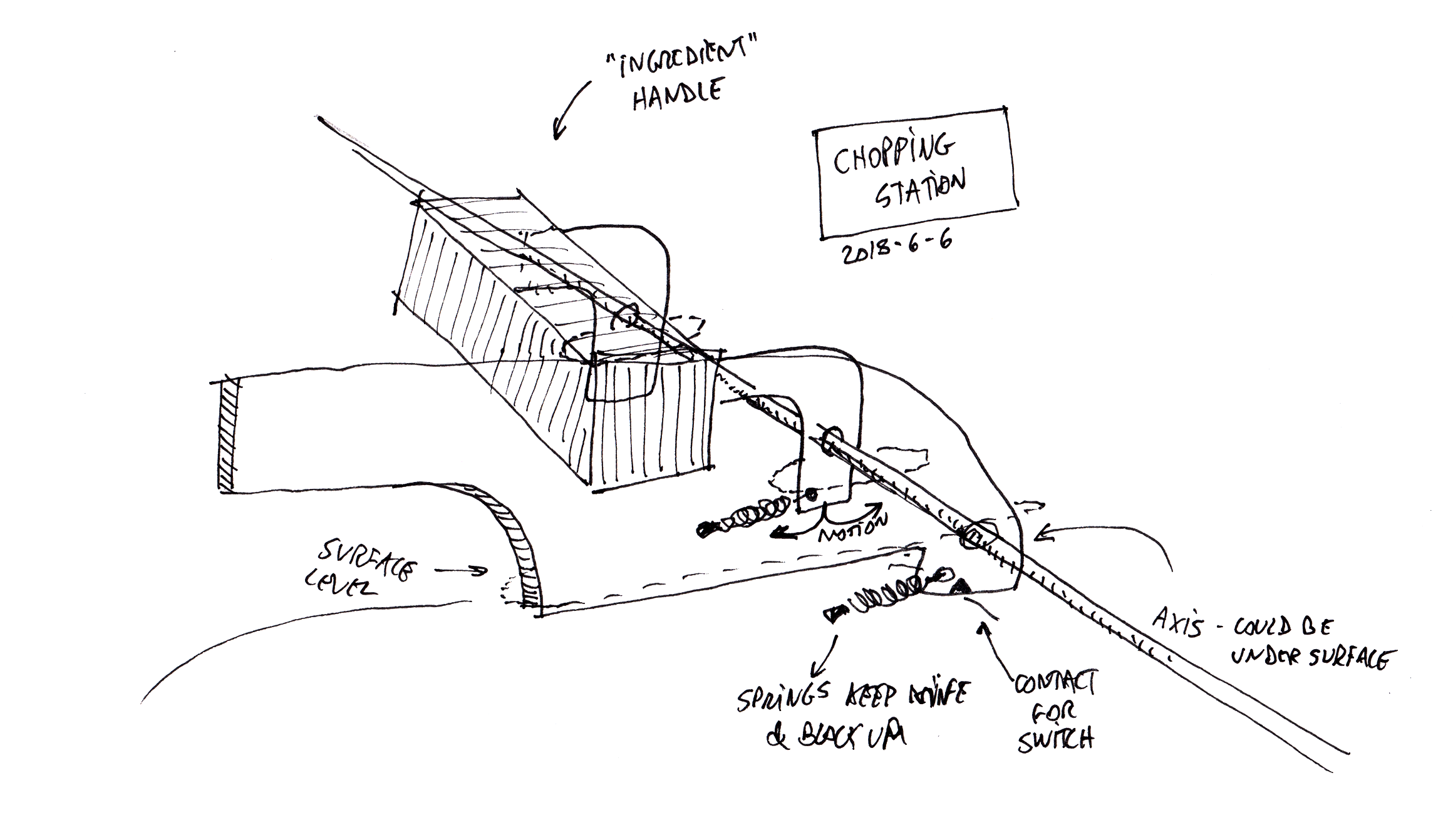

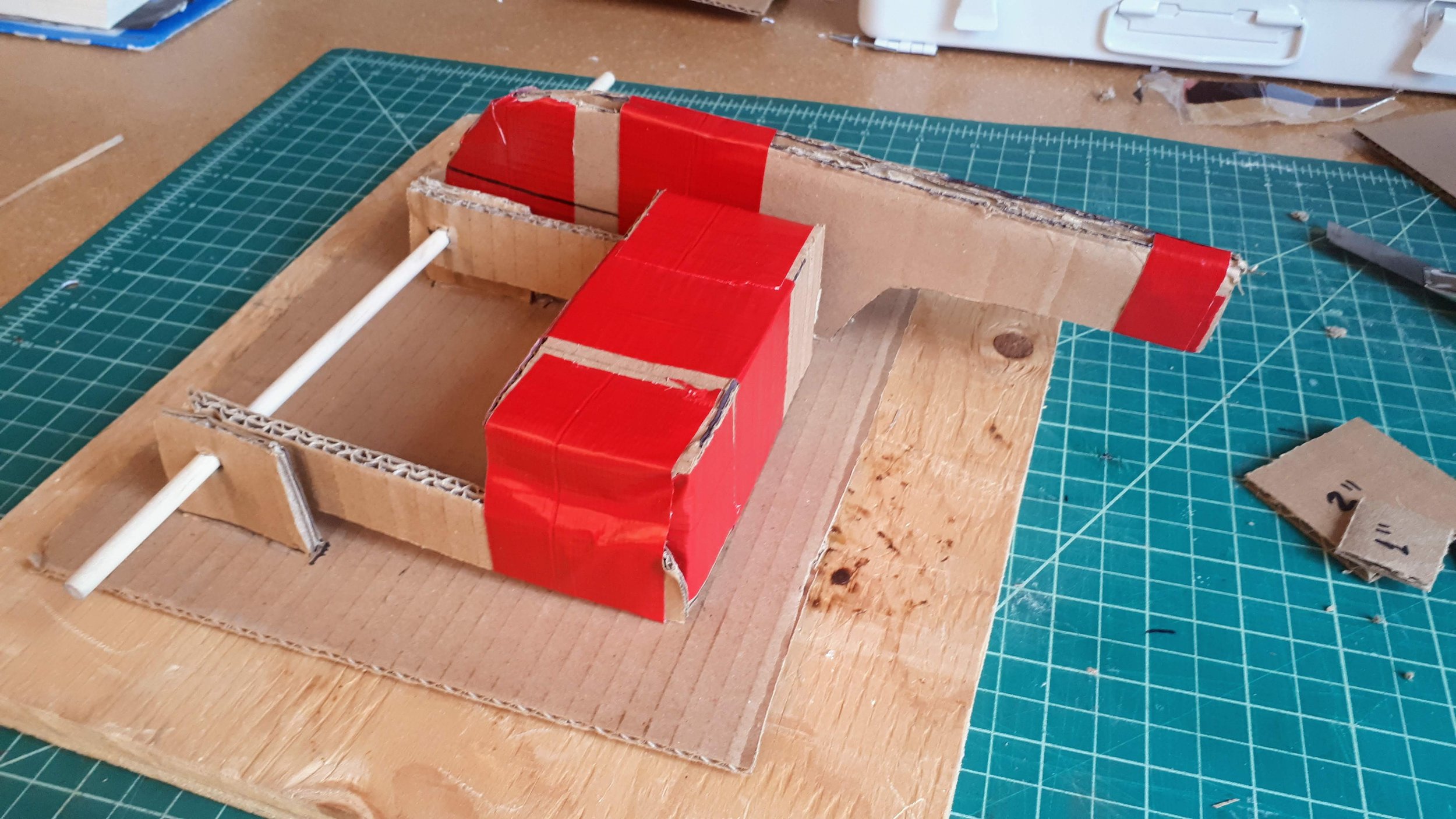

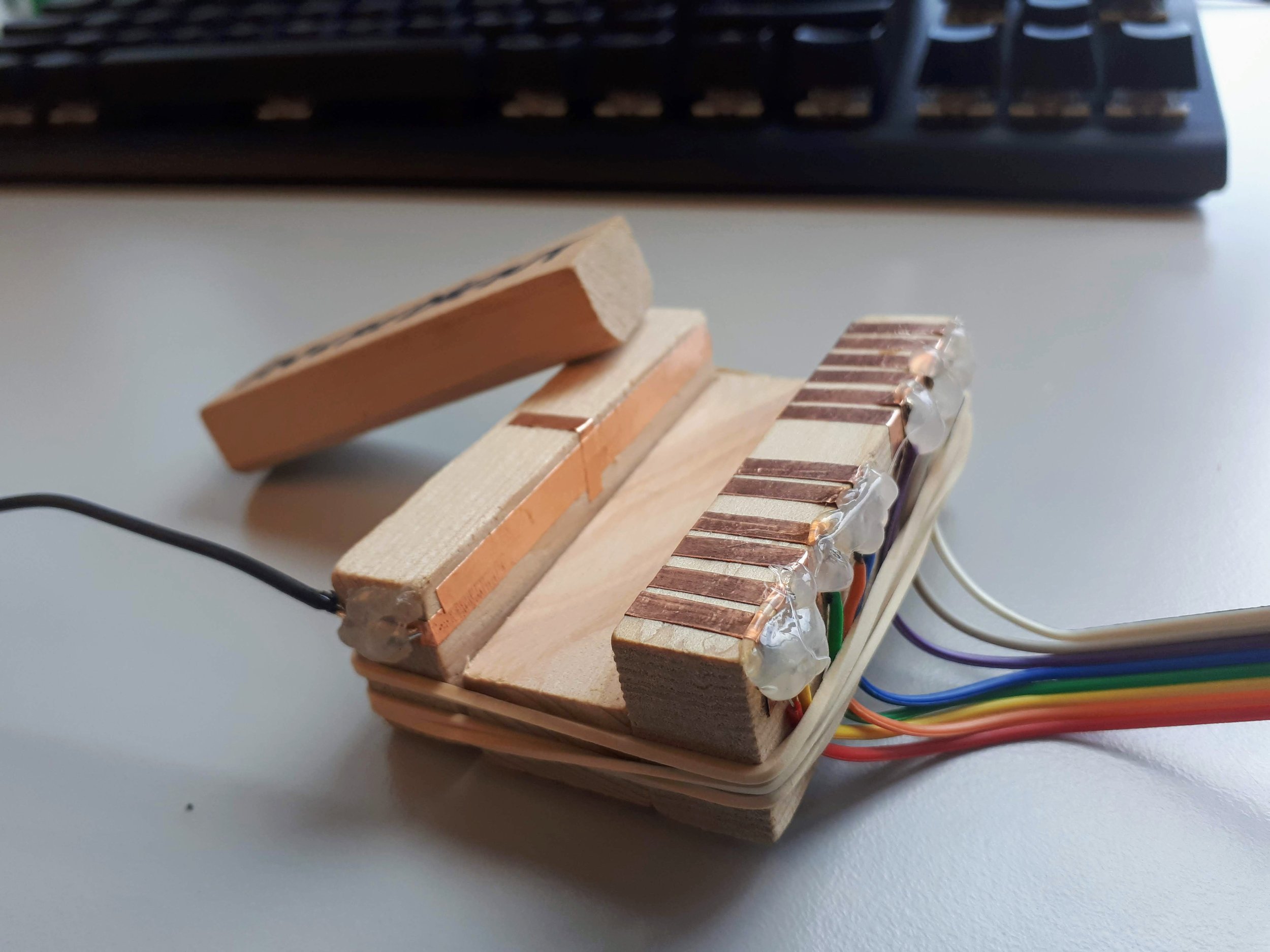

I use what I learned from the digital prototyping process to take the cooking station from sketch to working device. The process happens in iterations. I map specific cooking actions to different combinations of sensors and components: a stirring disk with a rotary encoder, potentiometers for water tap and heat, buttons for adding ingredients and serving dishes. I take note of their sizes and shapes to lay them out and test volumes.

In the game, as foodways are decontextualized and commodified, the control the judges exert is not only about their satisfaction of consuming the Other’s difference, but also about managing work. In terms of moment-to-moment play, this happens with regards to how the player handles instructions, tasks, and gestures through the cooking station device. Meanwhile, in terms of game world narrative, the in-game immigration system mirrors the real-life effect of regulating the flow of people and enforcing capitalist global organization of labor (Mezzadra & Neilson, 2013; Walia et al., 2021).

I wire the components to an Arduino board and start researching their documentation and programming. I then combine them in a playful control deck first and then in another shoebox prototype in which the different components are wired and functional, but not in a final arrangement. As I repeatedly enact the gestures of each component while programming and testing, the details of the final arrangement and layout take form. By November, I move on to more rigid materials for the prototypes. With my dimensions established, I design a 3D model of the controller, and use it to create a guide for laser-cutting an acrylic top surface, chopping knife and ingredient chips. This creates shiny, industrial looking objects for the cooking station. I combine these parts with a wooden case with rounded corners and a pot sculpted out of thermoplastic and a carton box.

Sourcing the Ingredients

Each recipe step is a combination of ingredients plus an action that players must perform. I consider materializing ingredients as an endless dial constantly being re-tuned. While this is a practical idea that I keep for the keyboard version of the game, I also want the ingredients to be tangible, separate pieces for handling. I consider repurposing plastic toys that imitate the different ingredients. I give up on this idea when it occurs to me how difficult these toy versions will be to source, maybe even harder than it is to find the meat cuts needed for an actual feijoada in Canada.

I reflect more on how the station will sense the ingredients and what their effects should be in the visa application system. They are distinct signals to qualify changes of state: bacon + chop, correct; kale + chop, incorrect. They refer to foodstuffs but functionally serve as control signals. In a way, the YES and NO ingredients used to answer survey-like questions while cooking are the most concrete ones in the game. I start to think of ingredients as standardized and immutable, as they are activated without contacting the surrounding tools (knives, pot, water tap) of the cooking station. They become lo-fi memory blocks that should be long lasting, reproducible, quickly replaced and repaired.

I start experimenting. I hot glue together contraptions made of cardboard bits and reused wooden toys. The wooden blocks come from a dollar store, which “smells of cheap” — an offhand, oblivious description by a Canadian acquaintance in the company of migrants who had just been expressing relief about being able to access affordable household goods when arriving in a new country. Is my game cheap if it uses dollar store toys?

As I balance the needs of project scope (budget, costs of parts, quantities, when/how to fabricate), I continue sketching electromechanic devices to connect the ingredients to the cooking station. I try levers, springs, wedges, but none make the cut. I wonder if I have hit a wall in this design direction.

Meanwhile, I explore materials for the cooking station case and the layout of on-screen graphics. At some point, after trying out a micro:bit board on a friend’s project, I test some edge card connectors. They fulfill the requirements needed for the ingredient-as-memory-cards concept perfectly: they are built for modular, repairable, and reliable connectivity. They are as dry as it gets. I look at my sketch and it dawns on me that I should have thought of using cartridges in my game earlier. I trek to an electronics shop to source an assortment of edge connectors. The friendly salesperson tells me that the components are “old tech” and I wonder if my ingredients are therefore also old by extension. Would my ingredients be fresher if I used a near-field communication (NFC) reader or some other wireless technology?

I test out different materials to get a consistent thickness for the memory cards. The same acrylic material of the cooking station fits them perfectly, with enough space for the bits of metal tape used as contacts. I get a transparent leftover sheet of plastic and laser cut the ingredient shapes and name each with a rotary labeler.

This transparent object changes how players use the ingredients, as their surface recedes. As in the idea of transparent gamepad or other ideally self-effacing control devices, the focus shifts beyond, to the task being performed (Kirkpatrick, 2009). The chips are backgrounded and minimized. Transparent computer components are a recurrent sci-fi trope, from 1970s Star Trek’s isolinear chips to 2010-20s The Expanse’s computer modules. The chips share a minimal footprint to human sensing and a payload understandable to machine sensing. They suggest high tech and effectiveness while working as props for the plot and actions taken, highlighting the player’s performance.

I appreciate the tension inherent in the transparent chips: they are props, but self-effacing ones. They work as “parts representing wholes designed to prompt speculation in the viewer about the world these objects belong to” (A. Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 92). The sci-fi trope anchors them as familiar in one direction. In another, the foods they refer to are estranged and abstracted away. The trope signals a fantastic level of control, and I design moments in the game that create friction with this image of the game system, with missing and mislabeled ingredients. In a way, the fantasy of efficiency is also undermined by how often these nice-looking ingredients break down, as the friction of inserting and removing ruins the electronic connection.

Sounding and Voicing a System

With the cooking station and ingredient chips ready, I dedicate a full day to sound design. While chiptune-y and synthesized sounds are my usual go-to audio aesthetics, I want to give in-game actions a richer texture, and for that I source recordings of cooking sounds. I mix them to be loud and slightly unrealistic, striving to make them distinct and recognizable. But they still closely reference the materiality of wet, organic ingredients and the felt experience of working with them, which contrasts with the dry materiality of the cooking station.

In terms of music, I investigate royalty free offerings that might fit the game. My previous experience with audio work has taught me how to undertake this process of sourcing background music tracks quickly. A specific track gets my attention, with its optimistic but repetitive structure, reminiscent of long waits endured on automated telephone services.

Because I approach all the text in the game as character dialogue, I think of the distinct lines as having particular voices. I plan for a kind of simplified and automated grammelot; one that is characterful and flexible, while also quick to create. Grammelot’s associations with satirical theater and comedy add to the general tone of the game and reinforce the notion that humor can take aim at dominant systems and discourses. Humor is key in critical game creation and reflection mocking hegemonic conventions (Harrer, 2019), and it plays an important role in queering and critical practices in human-computer interfaces (HCI), creating space for dissent through parody, inversion, and obliqueness (Light, 2011). Carolina Chmielewski Tanaka, my partner and an actor, creates and records the grammelot voices for each judge and for the application system messages.

On Repurposing Immigration Forms

As I prototype and playtest the game, I am repeatedly confronted by the dialogue of the immigration judges and the visual interfaces of the game. I rewrite and redesign these in bits and pieces, through rendering on slow boil. To perfect their tone, I track down some of my older and used up immigration forms and the information brochures I was handed when I entered Canada. The friendly tone of the brochures reproduces the state discourse of a welcoming Canada: humanitarian, tolerant, open (Sega, 2020).

I write in-game dialogue balancing the legal jargon of bureaucracy and authority with the calculated friendliness of customer service systems. I aim for the neutrality of a nice chat, a fair transaction, just the way things are. The presentation of information is utilitarian, banal, and everyday. The forms themselves are evocative objects insofar as their graphic design and text establish this everyday frame. I want to, as much as possible, connect the system in the game with the everyday character of systems of disciplinary power in capitalism, not to displace such systems into a “distant” elsewhere (see for instance Pope’s Papers, Please (3909 LLC, 2013), which explicitly evokes Soviet aesthetics).

The underlying systems called forth by these forms are not restricted to any particular country. In the RGD group, we discuss whether I want to make the game explicitly mention Canada as the country players are trying to go to. I include many references to the specifics of the Canadian system, particularly because it is often placed as an exemplar of openness (Ahmed, 2000; Walia et al., 2021) and because of my ongoing experiences with it. At the same time, I keep the connection implicit, as I want the critiqued discourse to be applicable to other countries that adopt (a variety of more or less) liberal approaches to multiculturalism such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and, to some extent, the United States of America. The decision to keep things implicit is also driven by nagging concern: might my own real-world immigration applications be affected if I explicitly critique the Canadian system? Political screening concerns are not far-fetched in the context of the USA’s requests for social media handles in visa applications (Travel.State.Gov, 2019) and Canadian border agents demanding impromptu phone searches (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2018).

The notion of the “form” and its extraction of information is present throughout the game. As I turn two feijoada side dishes into separate forms (in matters of immigration, it is rare to fill out just a single form), I am conscious of how immigration forms serve as technologies for engineering truths and facts. In the eyes of the nation, my foreignness is produced and shaped, my identity is contoured according to its senses. Forms establish a coherent regime of information to be digested by the state, across different agencies, for potential actualization in arbitrary futures.

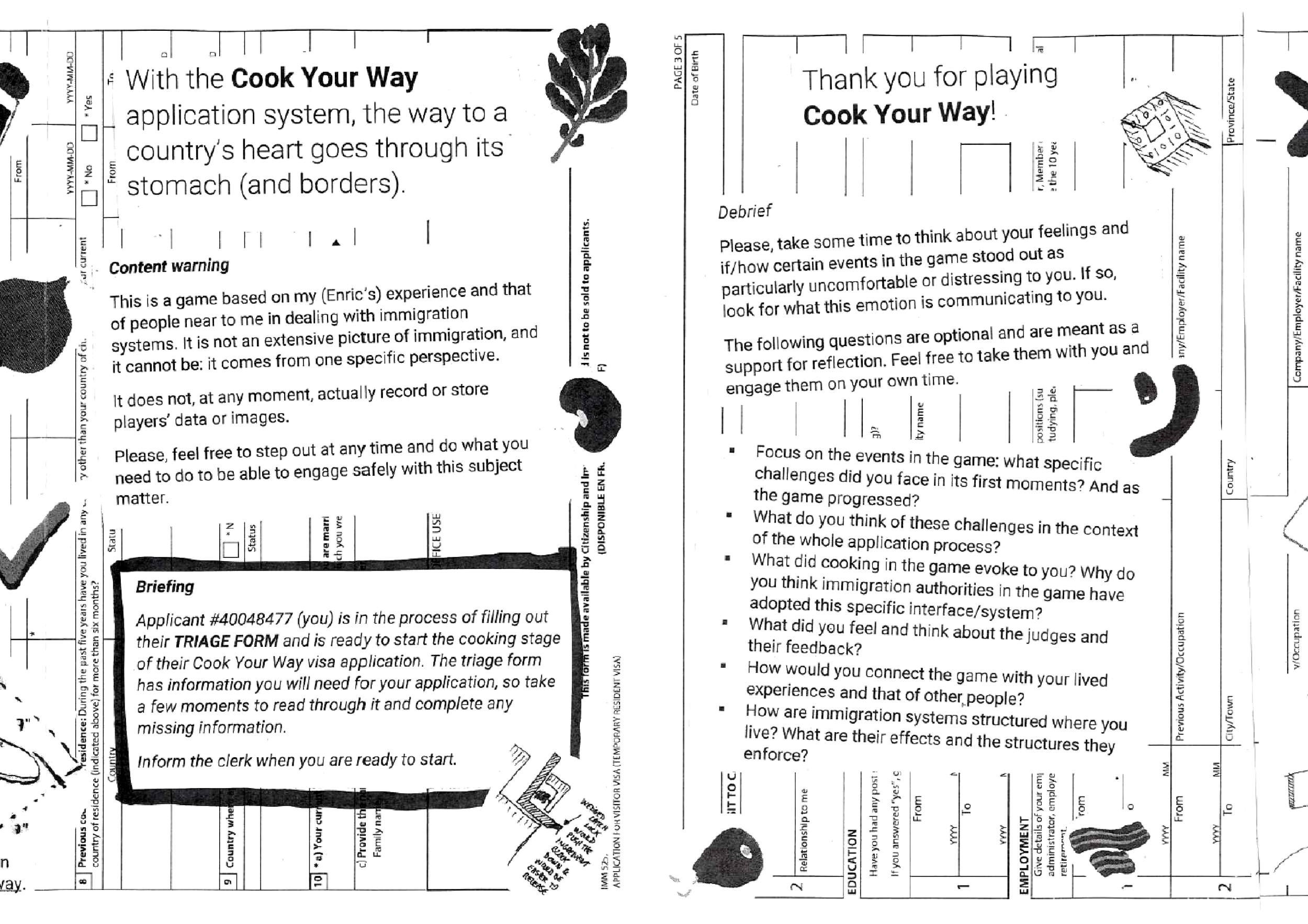

Zines as Brief and Debriefing

In an early RGD meeting, we discuss briefings and debriefings as transitions into and out of play sessions. Briefings and debriefings are part of the usual repertoire of simulation games and have been associated with supporting critical reflection (Crookall, 2014; Lederman, 1992; Stewart, 1992). I consider how to work them into the structure of CYW, because it occurs to me that supporting engagement with the questions raised by the game need not be limited to in-game moments.

I design a couple of zines to give to players before and after play sessions. The intro zine presents a content warning, disclaimers, and provides context for the game and its themes. Writing it lets me be upfront about how talking about immigration experiences also involves topics of stress and trauma, which is a concern I have with the game and how it mixes humor and critique. I cannot know the players’ histories and providing this introduction can help players better decide and prepare how they engage with the game. As I write the zine, I think that by giving space to the discomfort of the game, it also contextualizes its more chaotic and humorous aspects.

The intro explicitly favors clarity over stealth strategies (Khaled, 2018). It establishes a narrative prologue and features a TRIAGE FORM at its centerfold, which is a modified and half-completed version of a Canadian immigration form with my name on it, creating a bridge between forms in and out of the screen. When players are finished with the intro zine, they can start the game by telling the “clerk” that they are ready. There is some ambiguity here: who is this “clerk”, this institutional-sounding role in this play context, what is their role? Are they here to support the player or to surveil or both? At this point I am usually next to players as they read the zine and it tells them I am the creator of the game while also suggesting I am this clerk character, a part of the bureaucratic and institutional system they are about to interact with. This simultaneously diegetic and non-diegetic role allows me to both facilitate play when needed and describe to players these tensions and the larger scale of the in-game system.

The post-game zine presents a series of questions with which players can self-reflect, concerning their play experience and how it might connect to their personal history and context. It also provides ways to contact me if they want to reach out. I add small sketches and images of parts of the game to share how it came to be, a kind of trace to break the oft impermeable surface of complete technical objects. Players take the zines with them, a memento for them to re-narrate their experience in other contexts, further extending the limited circulation of the game.

A Meal and its Aftertaste

With the cooking station functional, most of the sound design done and a general tone for the writing established, I move on to writing up and refining the different stages of the game. I create a calibration stage to introduce players to the different components and elements of control, as well as the application system itself. I focus on crafting experiences of ever-increasing confusion for the player: survey questions about visa issues during cooking, ingredients that are inexplicably missing, interviews superimposed with cooking actions, new and unexplained cooking actions popping up at the final scene (washing, skimming fat). As the dishes and forms pile up for the player, the questions they are faced with move towards integration, work history, security.

When the game presents the final dish sequence, I shift the background music from the main theme heard throughout to a track called ‘Modern Jazz Samba’ by Kevin MacLeod. This shift makes the last scene ‘pop’: the tune is joyful and unrecognizable. I find it funny that the track has this title and sound, because to me it evokes another mix of jazz and samba — bossa nova — while still not really resembling it. ‘Modern Jazz Samba’ strikes me as a second-order or twice-removed adaptation that bypasses the histories and tensions of bossa nova (2), smoothing it over. I decide it is fitting for a moment in which the immigration judges turn their gaze, expectations, and machinery fully onto the main dish of the application, the feijoada itself.

I put in place the ending scenes of the game. After the player has finished cooking the feijoada, the judges ask for feedback about the application process to improve customer service. The idea here is to evoke the customer service-oriented language of institutional websites and systems, where interactions are framed as transactional. It is just good customer service practice.

And then, the application status changes.

If the overall quality and efficiency scores are too low, it is rejected outright. In every other case, the best possible result is ‘pending’ — after all, this is what happens in real world immigration processes. I intentionally withhold resolution here: I use anticlimax as an aesthetic and design strategy and I break with catharsis and identification to generate estrangement (Boal, 2008; D. J. Dunne, 2014; Khaled, 2018; Pötzsch, 2017).

The very last instruction the player receives is the following:

“Leave the premises. New applicants await.”

When I am close to finalizing the game, I document it together with Vjosana Shkurti to enter it into different showcases and competitions. In December 2018, I am notified that the game has been accepted at the altctrlGDC 2019 showcase, which will take place in March 2019 in San Francisco, USA.

Even though the custom-built cooking station has been designed to fit in a carry-on suitcase, it is still difficult to circulate the game, to make it available to players in a variety of contexts, and to travel with it. So far, it has only been exhibited in the Global North in venues associated with professional, academic, and artistic contexts. My current circumstances make it difficult to show it elsewhere, and I find this limiting.

At the same time, this means that the game circulates in events where there is a decent chance of encountering players with lived experiences of migration that overlap with mine. I have gratifying moments while showing and talking about the game, as players open up about their own experiences of migration and immigration systems. They look to me with complicity while scrambling for missing ingredients and answering certain questions, and readily share how different characteristics of the system resonate for them. Conversations also take place around how other game creators are approaching games about food and immigration.

When the game is accepted into the AMAZE 2020 festival, the question arises of how the game can be exhibited without its cooking station controller. With the onset of the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, the festival has changed to a fully online and remote format. Though I lack the time and resources to develop a festival-specific version at the conceptual level, the version I do develop functions without the original custom interface. This version reinstates the keyboard control mode I used during prototyping. I emphasize the brief/debrief zines, including them within the first screens of the game. I also prepare a virtual booth for the game that includes a photograph of the cooking station controller.

But I am aware that I am unnerved by the prospect of the game being exhibited without me there to help shape how it is understood.

In a way, this remediation of the game circles me back to my concern that the game may potentially be framed — by others — as an ‘immigrant simulator’ or empathy game that “can be used to translate experiences, helping those who have never experienced certain forms of oppression, trauma or disability to empathize with other people who have” (Pozo, 2018, n.p.). Distancing my work from this kind of approach is important to me. I agree with Polansky’s (2021, n.p.) critique of the deployment of empathy in the games industry: “the obsession with empathy, rather than a focus on building solidarity, erases the importance of history, class relations, and ideology from the equation of social change.”. The game does not ask non-migrant players to walk in my shoes and feel what it is like to be a migrant in contemporary Canada. It leverages aesthetic and design strategies to break with that kind of emotional framing and engage with systems of power from one particular perspective. However, the empathy game frame shapes interpretation as part of a larger context.

As I contemplate possible futures for the project in the current moment, such as elaborating the extant modding systems (Llagostera, 2019a), I reflect on how making CYW was a key process of navigating my situation in Canada. As well as forming the subject of untold conversations, it shaped my everyday interactions and focus of inquiry for two years. I consider whether and how to circulate CYW again and in which contexts. At the same time, I find myself wanting to move on to different projects that are less linear but still build on what I developed and learned with CYW.

For now, there it is — perched atop a box containing my actual visas, permits and authorizations — a visa application system sitting on a closet shelf.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the contributions of the members of the Reflective Game Design research group directed by Rilla Khaled: Rebecca Goodine, Jess Rowan Marcotte, and Dietrich Squinkifer. We also want to thank Vjosana Shkurti, Carolina Chmiewleski Tanaka, and the folks who generously played the game during development. Enric also would like to thank Otacilio de Oliveira Junior and Bruno Henrique de Paula for their thoughtful comments and insight during this paper’s writing. Cook Your Way was created with the support of the Hexagram Student Grant and the Technoculture, Art, and Games (TAG) research centre. Enric’s PhD research of which Cook Your Way is part of has received funding from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Societé et Culture (Doctoral Research Scholarship 2020-B2Z-276952).

Endnotes

1. A similar process is described and discussed in more detail by Sega (2020).

2. Bossa nova is a globally circulated genre that was central to Brazilian music and international image post-WWII, a contributor to Brazil being viewed as cosmopolitan. Bossa nova’s rise was contemporaneous with racial democracy being in vogue. Its original success is associated with white middle-class artists from Rio de Janeiro, while the central role of Afro-Brazilian artists in its formation (most notably Johnny Alf) is often downplayed (Sovik, 2009).

Author biographies

Enric is a game maker, educator, and researcher from São Paulo, Brazil. He is a PhD candidate at Concordia University (Tiohtià:ke/Montréal, Canada). His research focuses on questioning what is alternative about alternative controllers and on unconventional ways of making, circulating, and playing games. In 2019 he released Cook Your Way, a game about capitalism and immigration. He also worked on the gambi_abo series of open cardboard controllers and on altctrls.info, a website compiling information about making alternative controller games. More information on: https://enric.llagostera.com.br

Dr. Rilla Khaled is an Associate Professor in the Department of Design and Computation Arts at Concordia University in Montréal, Canada, where she teaches interaction design, serious game design, and programming, among other subjects. She is former director and steering member of the Technoculture, Art and Games (TAG) Research Centre, Canada’s most well-established games research lab, in the Milieux Institute for Arts, Culture, and Technology. Dr. Khaled’s research is focused on the use of interactive technologies to improve the human condition, a career-long passion that has led to diverse outcomes, including designing award-winning serious games, creating speculative prototypes of near-future technologies, developing a framework for game design specifically aimed at reflective outcomes, establishing approaches for capturing and reasoning about game design knowledge, and working with Indigenous communities to use contemporary technologies to imagine new, inclusive futures.

References

3903 LLC. (2013, August 8). Papers, Please. PC: 3909 LLC.

Ahmed, S. (2000). Strange encounters: Embodied others in post-coloniality. Routledge.

Aparecida Silva Bento, M. A. S. (2002). Branqueamento e branquitude no Brasil. In I. Carone & M. Aparecida Silva Bento (Eds.), Psicologia social do racismo: Estudos sobre branquitude e branqueamento no Brasil (pp. 5-58).Vozes.

Arat-Koç, S. (1999). Neo-liberalism, state restructuring and immigration: Changes in Canadian policies in the 1990s. Journal of Canadian Studies, 34(2), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.34.2.31

Arat-Koç, S. (2014). Rethinking whiteness, “culturalism”, and the bourgeoisie in the age of neoliberalism. In A. B. Bakan & E. Dua (Eds.), Theorizing anti-racism: Linkages in marxism and critical race theories (pp. 311-339). University of Toronto Press.

Ash, J. (2015). The interface envelope: Gaming, technology, power. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Back, J., Segura, E. M., & Waern, A. (2017). Designing for Transformative Play. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 24(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3057921

Belman, J., Nissenbaum, H., Flanagan, M., & Diamond, J. (2011). Grow-a-game: A tool for values conscious design and analysis of digital games. DiGRA Conference, 6, (1-15).

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim code. Polity.

Boal, A. (2008). Theatre of the oppressed (New ed.). Pluto Press.

Boling, E. (2010). The Need for Design Cases: Disseminating Design Knowledge. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v1i1.919

Brecht, B. (2005). Estudos sobre teatro (2nd ed.). Ed. Nova Fronteira.

Crookall, D. (2014). Engaging (in) gameplay and (in) debriefing. Simulation & Gaming, 45(4–5), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114559879

Dias de Souza, M. (2017). Feijoada quilombola: Chancela de etnicidade. Contextos Da Alimentação – Revista de Comportamento, Cultura e Sociedade, 5(2), 29-48. http://www3.sp.senac.br/hotsites/blogs/revistacontextos/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/3.pdf

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: Design, fiction, and social dreaming. MIT Press.

Dunne, D. J. (2014). Brechtian alienation in videogames. Press Start, 1(1), 79–99.

Dyer, R. (2006). Lighting for whiteness. In S. Manghani, A. Piper, & J. Simons (Eds.), Images: A reader (pp. 278–283). SAGE Publications.

Enric Granzotto Llagostera (2018). Cook Your Way.

Fajans, J. (2012). Brazilian food: Race, class and identity in regional cuisines. Berg.

Freyre, G. (2013). Casa-Grande e Senzala (Ed. comemorativa 80 anos.). Global.

Fron, J., Fullerton, T., Morie, J. F., & Pearce, C. (2007). The Hegemony of play. DiGRA Conference.

Fry, P. (1982). Para inglês ver: Identidade e política na cultura brasileira. Zahar Editores Rio de Janeiro.

Galloway, A. R. (2012). The interface effect. Polity.

Granzotto Llagostera, E. (2019a). Cook Your Way: Political game design with alternative controllers. Companion Publication of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2019 Companion, 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3301019.3325148

Granzotto Llagostera, E. (2019b). Critical controllers: How alternative game controllers foster reflective game design. Companion Publication of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2019 Companion, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1145/3301019.3324872

Gray, K. L. (2014). Race, gender, and deviance in Xbox Live: Theoretical perspectives from the virtual margins. Anderson Publishing.

Gvion, L. (2009). What’s cooking in America?. Food, Culture & Society, 12(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.2752/155280109X368660

Harrer, S. (2019). Intersexionality and the undie game. First Person Scholar. http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/intersexionality-and-the-undie-game/

hooks, b. (2006). Eating the other: Desire and resistance. In M. G. Durham & D. Kellner (Eds.), Media and cultural studies: Keyworks (Rev. ed, pp. 366–380). Blackwell.

Jacino, R. (2017). QUE MORRA O “HOMEM CORDIAL”—Crítica ao livro Raízes do Brasil, de Sérgio Buarque de Holanda. Sankofa (São Paulo), 10(19), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1983-6023.sank.2017.137189

Kamel, A. (2007). Não somos racistas. Nova Fronteira.

Keogh, B. (2018). A play of bodies: How we perceive videogames. MIT Press.

Khaled, R. (2018). Questions Over Answers: Reflective Game Design. In D. Cermak-Sassenrath (Ed.), Playful Disruption of Digital Media (pp. 3–27). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1891-6_1

Khaled, R., Lessard, J., & Barr, P. (2018). Documenting Trajectories in Design Space: A Methodology for Applied Game Design Research. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, pp. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3235765.3235767

Kirkpatrick, G. (2009). Controller, hand, screen: Aesthetic form in the computer game. Games and Culture, 4(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412008325484

Kultima, A. (2018). Game Design praxiology. Tampere University Press. http://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/103315

Lederman, L. C. (1992). Debriefing: Toward a systematic assessment of theory and practice. Simulation & Gaming, 23(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878192232003

Light, A. (2011). HCI as heterodoxy: Technologies of identity and the queering of interaction with computers. Interacting with Computers, 23(5), 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2011.02.002

Maciel, M. E. (2004). Uma cozinha à brasileira. Revista Estudos Históricos, 1(33), 25–39.

Marcotte, J. (2018). Queering control(lers) through reflective game design practices. Game Studies, 18(3). http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/marcotte

Mezzadra, S., & Neilson, B. (2013). Border as method, or, the multiplication of labor. Duke University Press.

Nakamura, L. (2009). Interfaces of identity: oriental traitors and telematic profiling in 24. Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, 24(1), 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-2008-016

Nascimento, A. do. (1978). O Genocidio do negro Brasileiro: Processo de um racismo mascarado. Paz e Terra.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. (2018, December). Your privacy at airports and borders. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/airports-and-borders/your-privacy-at-airports-and-borders/#toc1a

Pias, C. (2011). The game player’s duty: The user as the gestalt of the ports. In E. Huhtamo & J. Parikka (Eds.) Media Archaeology Approaches, Applications, and Implications (pp. 164-183). University of California Press.

Polansky, L. (2021). Part III: The fuzzy science and art of empathy. Rhizome. http://rhizome.org/editorial/2021/mar/24/part-iii-the-fuzzy-science-and-art-of-empathy/

Pötzsch, H. (2017). Playing Games with Shklovsky, Brecht, and Boal: Ostranenie, v-effect, and spect-actors as analytical tools for Game Studies. Game Studies, 17(2). http://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/potzsch

Pozo, T. (2018). Queer games after empathy: Feminism and haptic game design aesthetics from consent to cuteness to the radically soft. Game Studies, 18(3). http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/pozo

Sax, D. (2017, March 27). The sriracha argument for immigration. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-sriracha-argument-for-immigration

Sega, R. F. (2020). Produções ciborgues: Imigrantes brasileiras & mídias sociais no Canadá [PhD, Universidade Estadual de Campinas]. http://repositorio.unicamp.br/jspui/handle/REPOSIP/351221

Shields, J., Kelly, P., Park, S., Prier, N., & Fang, T. (2012). Profiling immigrant poverty in Canada: A 2006 census statistical portrait. Canadian Review of Social Policy / Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale, 0(65–66). https://crsp.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/crsp/article/view/35245

Shkurti, V. (2018, November 30). COOK YOUR WAY: game trailer. https://vimeo.com/303835628.

Souza, C. P. S. de. (2016). A feijoada da Portela: Um olhar sobre a percepção da comunidade quanto à presença de visitantes. Repositoro http://www.repositorio.uff.br/jspui/handle/1/1449

Sovik, L. R. (2009). Aqui ninguém é branco. Aeroplano Editora.

Stewart, L. P. (1992). Ethical Issues in Postexperimental and Postexperiential Debriefing. Simulation & Gaming, 23(2), 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878192232007

Thobani, S. 1957-. (2007). Exalted subjects: Studies in the making of race and nation in Canada (Vol. 1–1 online resource (xiii, 410 pages)). University of Toronto Press; WorldCat.org. https://www-deslibris-ca.lib-ezproxy.concordia.ca/ID/418977

Travel.State.Gov. (2019, June 4). Collection of Social Media Identifiers from U.S. Visa Applicants. https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/News/visas-news/20190604_collection-of-social-media-identifiers-from-U.-S.-visa-applicants.html

van Ryn, L. (2013). Gestural economy and cooking mama: Playing with the politics of natural user interfaces. Scan – Journal of Media Arts Culture, 199.

Vilela dos Santos, T. (2018, May 17). [ALT CTRL] Game design beyond screens & joysticks—Introduction (1/5). Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/-alt-ctrl-game-design-beyond-screens-joysticks—introduction-1-5-

Walia, H., Kelley, R. D. G., & Estes, N. (2021). Border and rule: Global migration, capitalism, and the rise of racist nationalism. Haymarket Books.