by Henri M. Nerg

Published February 2024

Download full pdf of article here.

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyze and explain character affectivity through a case study of a Japanese visual novel, Newton and the Apple Tree (Laplacian, 2017). The paper analyzes different affects and emotions the game’s characters are coded to evoke in players. Affect is understood here following affective neuroscience, which recognizes seven primary emotions in humans and animals. This theory is accompanied by a larger theoretical framework combining the studies of Japanese popular culture, thus placing the study in its regional context, as well as game studies. The study shows how fictional characters act as major elements in evoking the affects experienced by players. The paper connects the qualitative analysis of characters, narrative and the world surrounding them with categorization of empirically studied primary affects and emotions. The paper offers a new emotion-centered framework for analysis of visual novels, and a larger framework and model for analyzing different art and media works.

Keywords: affect, emotion, characters, Japan, visual novel

Introduction

Visual novels, interactive and narrative text-based games mostly made for personal computers, are a major and unique phenomenon of the transmedia world of Japanese popular culture. Even though not globally renowned as anime and manga, they are still an important part of the otaku culture—a subculture centered around anime, manga, videogames and other forms of Japanese popular culture (Azuma, 2009, p. 3)—and its representations and manifestations. They are a medium and art form mixing interactive gameplay with narrative and literary content, as well as the distinctive aural and visual style of other works of Japanese popular culture (see Cavallaro, 2009).

This study focuses on character affectivity in the Japanese visual novel Newton and the Apple Tree (Laplacian, 2017). Ultimately, the goal is to offer a new framework for better understanding how emotions can surface and manifest themselves in a narrative artwork, with possible future

applications to other media and genres as well. A visual novel was chosen as a case study for the study of affects evoked by fictional characters for its qualities as a form of media and as an art form, combining different narrative, interactive and audiovisual qualities that are complex in their affective features. Through an analysis of a visual novel one can analyze a set of diverse qualities, features and elements that different works of media and art use to evoke affective reactions in their consumers. The study is based on a qualitative analysis of Newton and the Apple Tree conducted in the form of a close and thorough reading of the game as a whole, using Jaak Panksepp and Lucy Biven’s (2012, pp. 38–40) affect theory as a framework, that is based on empirical observations. The study complements the analysis with a consideration of play-time and its effects on the gaming experience with a focus on its affective dimension.

Panksepp and Biven (2012, p. 2) have identified and categorized seven primary emotions in both humans and animals: seeking, rage/anger, fear, lust, care, panic/sadness and play (1). These primary emotions have developed across human and non-human animals for reasons of survival and establishing social relationships, as evidenced by increasingly accumulating literature (Bacha, 2019; Davis & Montag, 2019; van der Westhuizen & Solms, 2017; Watt, 2017). Following this literature, I define affect as an emotional reaction evoked by an external stimulus that expresses some of the seven aforementioned primary emotions, whereas emotion (colloquially) is a more complex concept that is built over primary emotions and affects. Brief descriptions of the affects are summarized in Table 1:

| Primary Emotion | Affect |

|---|---|

| Seeking | An energetic desire and manifestation of seeking and searching |

| Rage/Anger | Abrupt manifestation of anger and rage |

| Fear | Manifestation of fear or fight or flight reaction |

| Lust | Manifestation of sexual desire and lust |

| Care | Manifestation of strong tenderness and nurturing |

| Panic/Sadness | Manifestation of strong shock and grief |

| Play | Physical manifestation of abrupt and rapidly changing action |

The game providing the case study has been selected for several reasons. It is a conventional example of a subgenre of eroge visual novels, which focus on the male character’s interactions with multiple sexually provocative girls (Galbraith, 2011). Very often the main function of these games is to act as so-called dating simulators, where the player makes choices resulting in the male main character pursuing a sexual relationship with the desired female non-player character. The game features a long and complex narrative, drawing on elements of history and natural sciences, thus transcending its primarily pornographic genre and incorporating

other genres as well. The case study was chosen as its themes and narrative have the potential to evoke all seven primary emotions. A specifically Japanese visual novel was chosen because the characteristics of Japanese popular culture include strong expressions of affective and emotional elements. Analyzing these seven primary emotions will contribute to an increased understanding of the importance of character affectivity in visual novels. As the academic study of visual novels is still sparse in English (but not completely nonexistent, see Cavallaro, 2009; Galbraith, 2011; Okabe & Pelletier-Gagnon, 2019; Pelletier-Gagnon & Picard, 2015; Taylor, 2007), more interdisciplinary research is needed to understand the unique phenomenon of visual novels.

First, the study introduces visual novels in the context of Japanese transmedia popular culture and other forms of interactive fiction, as well as the game in question. Successively, it introduces affect as a concept derived from neuroscience to understand the effects the game’s characters have on the player and how they are constituted and analyzes these affects in Newton and the Apple Tree via close reading from audiovisual and temporal-narrative viewpoints, examining how the game offers a good example of how affectivity is constructed. The analysis highlights how different affects are coded into the different elements of the game to evoke those affects in the player. The analysis shows in detail which formal elements and features contribute to which affect, how they are constructed and how these codings contribute to the players’ responses evolving into more complex emotions. Overall, the article contributes with a thorough case study showing how a visual novel is coded as to evoke different affects, and furthermore provides a framework applicable to other forms of art and media as well.

Visual Novels and Their Characteristics

Visual novels, as their denomination suggests, are often considered closer to literature than videogames despite their interactive and audiovisual qualities (Galbraith, 2011). This is due to the fact that most visual novels feature far stronger emphasis on narrative and character development compared to interactive elements. As in literature, visual novels are generally focalized through the male main character. Arjoranta (2015, pp. 4–9) categorizes focalization in videogames in three main categories: zero focalization, external focalization and internal focalization. Visual novels typically feature internal focalization, which Arjoranta (2015, p. 7) describes as occurring in games with frequencies similar to those in literature. As visual novels share several major elements and qualities with literature, a comparison between the two mediums is adequate and useful. Internal focalization supports affectivity towards the main character by making his inner thoughts and feelings visible. This is underscored by the fact that many of the interactive choices the player makes do not affect the outcome of the game, as they all lead to the same conclusion. Only a handful of (mostly binary) choices actually affect the story itself in the case of dating-simulation and eroge games (see Taylor 2007, p. 194).

Compared to many other forms of videogames, visual novels feature relatively small amount of player interaction. Most of the gameplay consists of the player repeatedly pressing the enter-button to progress the story and reading the narration and dialogue, while simultaneously listening to the dialogue spoken by other than the main character. Alternatively, the game can be set to “auto mode” with a desired speed, so the interactive game mechanics are reduced to occasionally making a choice. This means different players can have radically different experiences because of the interactive quality of visual novels. This can be understood through Karhulahti’s (2015) notion of supradiscourse, defined as “an actualized empirical discourse interaction sequence” (p. 46). For example, two readers reading the same book engage in a different supradiscourse as they inevitably read at a different pace and pay more attention to certain passages than others. The supradiscourses between visual novel players can vary radically when considering the interactive qualities of the game. The narrative unfolds in different ways, depending on which order the player finishes the game.

Suprastory, in turn, is defined by Karhulahti (2015) as “an actualized conceptual story construct” (p. 47), referring to the mental process of the consumer of the work. As every consumer constructs their own suprastory, in the context of an interactive game the differences between players’ suprastories become more meaningful when considering the players’ cognitive processes of affectivity. In other words, even if two players read a game with exactly the same speed and focus, they would still experience it differently due to their subjective differences that may, for instance, make one react affectively to events in different ways.

The case study of this article falls into the genre of eroge, which emphasizes the sexual actions and affective qualities of the characters that are defined by so-called chara-moe elements. Chara-moe elements tend to trigger affective, nurturing and sometimes sexual feelings and desires in players. Most of the chara-moe elements are visual by nature, including colorful and stereotypically feminine and cute appearance of (female) characters, but chara-moe elements also cover narrative and thematic qualities of the work. (Azuma, 2009, p. 42; Galbraith, 2009; Lamarre, 2009, pp. 258–259). In the context of Japanese popular culture, the most visible tools for creating affection are visual characteristics, some being unique to Japanese popular culture. These characteristics include chara-moe stylized character rendering (Azuma, 2009, p. 42; Galbraith, 2009).

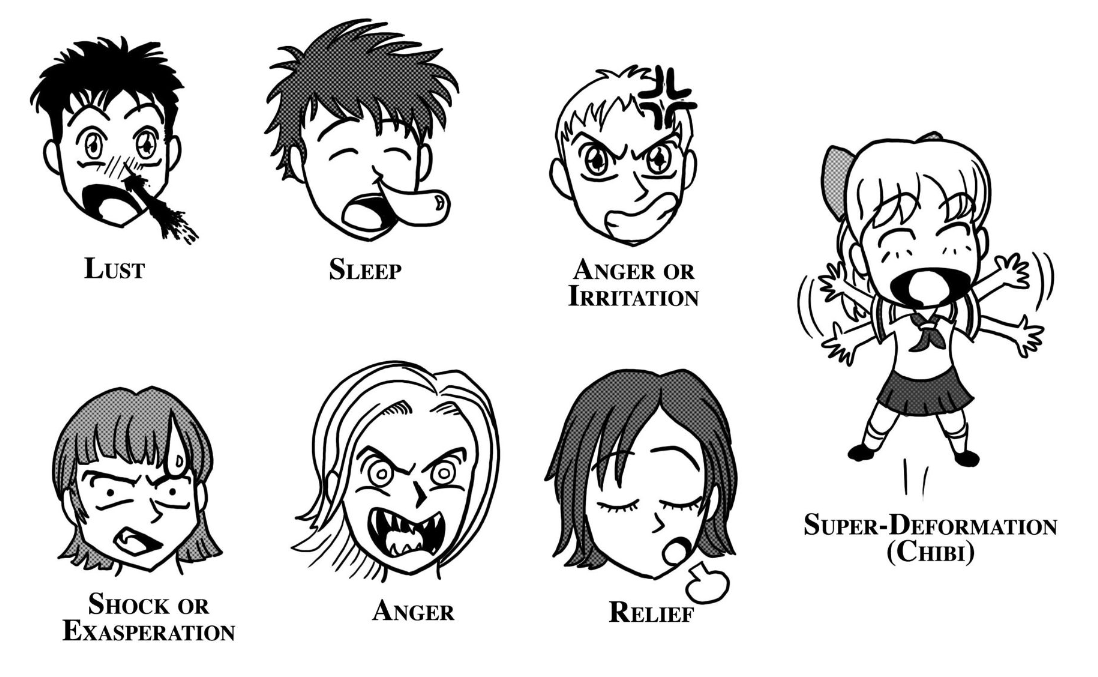

Neil Cohn (2010, pp. 187–190) has studied the grammar of manga that they call Japanese Visual Language (JVL). As the ecosystem of Japanese popular culture is strongly transmedial by nature, the visual language of manga largely applies to anime and visual novels as well, therefore making the comparison between the different media and art forms worthwhile. Cohn (2010, p. 193) categorizes what they call “graphic emblems” of manga expressing characters’ emotion and constructing the grammar of manga (see Figure 1).

Pelletier-Gagnon and Picard (2015, pp. 31–32) have mapped the history of erotic and pornographic videogames in Japan, which traces back to the very beginning of the larger videogaming culture emerging in Japan in the 1980s. During the 1990s and 2000s, many eroge games that put more emphasis on the (melo)dramatic content, story and character development started to emerge, thus pushing the genre slightly into a more mainstream direction, which is linked to otaku culture becoming more mainstream in general (pp. 35–37). The erotic and pornographic games, in addition to the medium of visual novels itself, have entered Western gaming discourse as well, mainly starting since the 1990s (pp. 37–39).

Eroge games are mainly targeted and marketed towards heterosexual men, as can be seen from their visual language, character depiction and storytelling. The male main character acts as a surrogate for the assumed heterosexual male player (Taylor, 2007, p. 198), through whose focalization the player sees the game. The dialogue of the main character can only be read as a scrolling text, whereas all the other characters’ dialogue is voice-acted and accompanied by the dialogue in written form. Additionally, the still images and animation of dating-simulation games evoke the (male) gaze, as the point-of-view is strictly limited to the main character who is very rarely seen on the screen. The main character is often lacking in personal qualities that would make him a multi-dimensional character. Taylor (2007) even goes so far as calling male characters “essentially empty shells” (p. 198). It is true that usually the male main characters are depicted as “ordinary men.” However, calling them “empty shells” is an oversimplification, as it reduces affectively significant characters to purely functional narrative components. The stories themselves cannot unfold without the main character driving them, nor can characters be experienced as “deep” or “more affective” if not compared to characters who share more or less of these qualities.

While many pornographic visual novels lack complex plot and character development, emphasizing instead pornographic content, this is not always the case. There exists a major subgenre of pornographic visual novels which feature surprisingly little explicit content. Azuma (2009, p. 78) argues that these games are not designed to provide erotic satisfaction but to elicit feelings of sorrow and joy, and refers to them as melodramas instead of pornography. Indeed, these kinds of visual novels (e.g. Kanon, 1999, and Air, 2000, mentioned by Azuma) differ significantly from other forms of pornography, which focus on depictions of sexual acts.

I adopt a pragmatic definition of pornography—that is, pornography is media designed to evoke sexual desire and arousal by depicting sexual acts and fantasies. I am inspired here by Nguyen and Williams’s (2020) definition of pornography as “a representation of sexual content, primarily used for the purpose of a gratifying reaction, freed from the usual effort and consequences of sexual interaction” (p. 157). As eroge visual novels are marketed and consumed as pornography (see Azuma, 2009; Galbraith, 2011; Taylor, 2007), I see my definition based on the pragmatic and common usage of sexual pornography as relevant in the context of this paper.

As with other forms of videogaming, temporality plays a major role in constructing affectivity in visual novels (cf. Juul, 2013, p. 29). Several visual novels take hours to complete even via the shortest possible routes, and dozens of hours to unlock all the possible storylines. Anders Tychsen and Michael Hitchens (2009) developed a model for categorizing and analyzing game time. The model is mostly tested empirically on multiplayer role-playing games, but it can be applied to visual novels as well. In Newton and the Apple Tree, the concept of time is multilayered and manifests itself in different ways due to the game’s nonlinear temporality in the gameworld itself. Tychsen and Hitchens categorize nonlinear representations of game time as following:

1. Progress time: abstract and individual view of the game time that varies according to the player;

2. Story time: logical and chronological time of the dramatic story of the game;

3. World time: time as it occurs in the game world. (pp. 188–192)

Progress time is strongly linked to the player’s ability to experience affection towards characters, as it is directly related to the player’s cognitive abilities to process the information of the game. This is manifested in the fact that players’ progress times can differ significantly as well the fact that certain characters more than others may feature more heavily within different players’ progress time, changing the supradiscourse, even though the storyline might be the same (cf. Karhulahti, 2015). Temporality is a particularly interesting aspect when considering pornographic content. As pornographic media mostly aims at instant gratification of sexual urges and is used as an aid for masturbation (Nguyen & Williams, 2020, pp. 157), it typically is centered around the pornographic content whereas other elements are reduced to mere instrumental elements of a (mostly) logical and coherent story.

Visual novels mainly share a common goal, which is to provide a satisfying ending to a story. This happens through the playing of different routes and finding a storyline that either satisfies the player personally, or is considered an “objectively” satisfying ending. By this I mean that the ending gives the player a sense of completion on the level of the story or the characters. A sense of completion may also feature evoked by pornographic content, which according to Pelletier-Gagnon and Picard (2015, p. 30) has been used as an incentive reward for the player ever since the early years of visual novels in the 1980s.

Newton and the Apple Tree

Newton and the Apple Tree (ニュートンと林檎の樹, 2017; abbreviated Newton further in the text) is a Japanese visual novel developed by Laplacian and released by Sol Press. The game revolves around a young man named Asanaga Syuji, who has abandoned his childhood dreams to become a renowned physicist following the footsteps of his famous grandfather Asanaga Syuichiro. Syuji’s childhood friend, Utakane Yotsuko, persuades him to travel to England, where Syuichiro has left without notice several years ago, after Yotsuko receives a package from Syuichiro containing a key. Upon travelling to England and finding a Newtonian telescope into which the key fits, Syuji and Yotsuko travel through time to the year 1687, when Isaac Newton is supposed to have published a thesis on the law of universal gravitation. However, they realize that in reality Newton is a pseudonym of a young girl named Alice Bedford, and that upon travelling back in time they have created a time paradox that has prevented Alice making the groundbreaking scientific discovery of universal gravitation that would form the scientific progress of humanity for centuries to come.

Newton features five female characters whom Syuji can pursue. The first one introduced is Yotsuko, Syuji’s childhood friend, who has made a promise with Syuji to meet in the future and continue doing science; however, Syuji has abandoned this life trajectory in favor of performing music as a street artist. The second girl introduced is Alice, the genius physicist behind Newton’s pseudonym. Despite her intelligence, she often acts in a childish manner especially towards Syuji, whom she constantly pejoratively calls perverted idiot, even though she eventually develops romantic feelings towards him. The other three girls are Lavi, an eccentric French physicist and innovator with a perverse imagination; Haru, a shy Japanese student wishing to visit her homeland some day; and Emmy, a cheerful maid who later shows a remarkable knowledge of physics despite having never having studied it formally or academically, and who is later revealed to be Alice’s half-sister in Emmy and Alice’s storylines.

Newton is arguably a dating-simulation game, where the main purpose is to match the male main character with the player’s preferred female non-player character; this subgenre aimed at a male heterosexual audience is called bishōjo (Blom, 2020, p. 5). The interactive choices made by the player influence whom the main character will successfully pursue. In eroge games, the key outcomes are sexual scenes, though in many dating-simulation games these may also be forming a romantic relationship with the non-player character usually interpreted as a happy ending. Newton is also an archetypal melodramatic eroge game, described by Galbraith (2021) as being “much like soap operas, centered on relationships and emotional responses, which contributes to attunement to slight movements of bodies in images dense with potential meaning” (p. 132).

According to Japanese law regarding pornographic images, eroge games alongside other explicitly pornographic media must be released in a censored form within Japan (Japanese Law Criminal Code, 2020). Normally, the censorship is applied by either mosaicking the explicit images of genitals, or just omitting those images. The English version of Newton was released in both an uncensored version and a “+17 version” which includes some sexual scenes but omits the most explicit content (Steam, 2020). The analysis of this paper is based on the English-language uncensored version, which also contains the original Japanese-language dialogue.

I consider Newton a genre hybrid comprising elements of melodrama, science fiction and pornography. The fact that all these genres affect players in different ways makes the game a particularly rich case study.

Affective Neuroscience and Evocative Stimuli

Affect has multiple and radically varying definitions in different scientific fields. In game studies, play experiences may elicit affects within players that are analyzed from different theoretical perspectives. My understanding of affect is based on neurocognitive sciences, even though I contribute to a humanities-oriented field and apply several humanities-derived methods and concepts. Previously, affect theory has been applied to several fields of the humanities, including game studies (e.g. Anable, 2018). However, the goal of this study is to map out affects systematically to understand how and in what ways affects manifest, impact on players and are evoked by the unique aspects of the medium of visual novels. My approach starts at the micro-level of affective neuroscience and expands to a more macro-level of humanities theories.

Aubrey Anable (2018) understands videogames “not as containers of and for affects that float around between bodies and things but rather as media that have specific affective dimensions, legible in their images, algorithms, temporalities, and narratives, that can be interpreted and analyzed” (p. 7). I equally approach the specific qualities of visual novels in terms of how their form is essential in constructing affects. Anable also quotes Eugenie Brinkema (2014), who writes that the premise for their understanding of affect is that “affective force works over form, that forms are auto-affectively charged, and that affects take shape in the details of specific visual forms and temporal structures” (p. 37). I agree with Brinkema, in that affects are “auto-affectively charged” and that they are manifested through specific mediums in various ways. I believe that a useful, yet previously unmapped, way to understand the intersection of media and affect is through affective neuroscience and through their roots in evolutionary and neurobiological psychology.

The main reason I have chosen affective neuroscience (Panksepp, 1998) as a theoretical background is it offers a useful model for systematic analysis and categorization of affects and emotions applicable to a variety of other media analyses and studies as well. What affective neuroscience does differently than humanities-oriented affect theories is that it derives from decades of cross-species research on how—and what—emotions might exist. A categorization based on neurosciences offers new interesting ways to understand affects, which lay a foundation for complex emotions. Combining humanities methods with affective neuroscience allows us to understand more about how affects are created, formed and play out in media experiences.

My framework based on neuroscientists Panksepp and Biven’s (2012, p. 2) seven primary emotions offers a simple and clear categorization of primary emotions expressed in the case study, which in its part also makes possible a flexible and deeper close reading and other forms of analyses for the affects and the game itself. Neuroscientific studies also offer a strong link between the fictional gameworld and real-life affects and emotions rooted in human psychology. Otaku culture is often criticized for being out of touch with reality, forming its own closed digital environment (see e.g. Saitō, 2011). This understanding largely frames the ways otaku-related phenomena are researched. Therefore, interfacing otaku culture with modern neuroscience helps placing the phenomena in “life” context.

In the next section, I analyze Newton through visual, auditive and temporal-narrative elements. The analysis was conducted as a close reading, followed by a coding of the affects evoked by the characters through the lens of affective neuroscience and the author’s personal emotions evoked during the gameplay. The analysis of individual affects was successively tied into a larger context by analyzing them through the lens of temporality and the modality of visual novels. While the results may not be fully reproducible due to the individual differences across readers, the methodology, on the other hand, is, and readers of this study are encouraged to reflect on whether the given examples evoke similar responses in them.

Visual, Auditive and Temporal-Narrative Stimuli

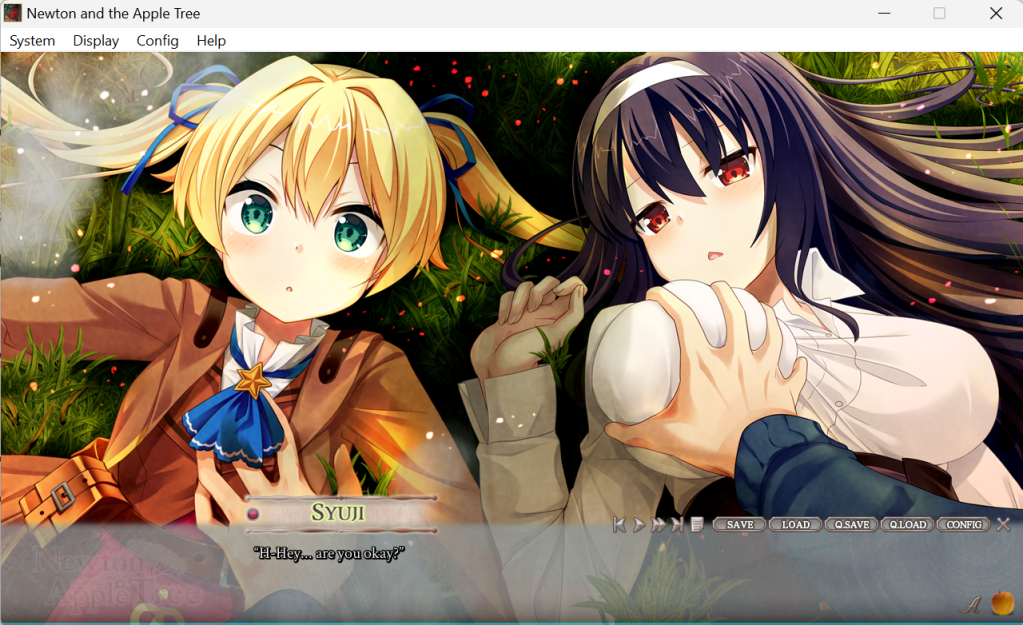

In the context of Japanese popular culture, the most visible tools for creating affection are visual characteristics. Some of these characteristics are unique to Japanese popular culture, such as the chara-moe stylized character rendering seen in the characters of Newton (Figure 2). All characters have big eyes (especially compared to their noses and mouths), colorful hair and clothes and simple facial renderings. Even though they are adults, they look very child-like (2). As Azuma (2009, pp. 42–47) points out, cuteness is an important and distinguishable feature of Japanese popular culture in general. Characters speak in a high-pitched voice, especially those who express “cute” and “feminine” tropes, like Emmy and Haru.

As seen in Cohn’s graphic emblems in Figure 1 and the graphic design of Newton in Figure 2, the characters’ visual rendering in Japanese popular culture are coded to express evocatively primary emotions. The graphic emblems of shock and anger correspond with Panksepp’s categorization, while the characteristic graphic emblem of chibi can be interpreted as an expression of play. The characters of Newton have only a handful of facial expressions, with eyes and mouth being the main marker amongst them (see Figures 3–6).

Figures 3 (left) and 4 (right): Examples of Alice’s facial expressions in Newton and the Apple Tree (2017) that are coded to evoke positively charged affects.

Figures 5 (left) and 6 (right): Examples of Alice’s facial expressions in Newton and the Apple Tree (2017) that are coded to evoke negatively charged affects.

The facial expressions of Alice in Figures 3 and 4 are characterized by closed eyes and smiling or kissing mouth. The downwards tilted eyelids and upwards tilted mouth are similar to the round form of the character’s head. These facial expressions are coded as to evoke positively charged affects such as lust, care and play. In Figures 5 and 6, Alice’s eyes and mouth are open and, in Figure 5, her cheeks are blushing. These small changes shift the affective focus into negatively charged affects such as rage/anger and panic/sadness. As can be seen from Cohn’s categorization of graphic emblems in Figure 1, the same connection between closed and open eyes can be drawn, though it should be clearly stated that this cannot be applied to all facial expressions.

These affects are accompanied by the game’s music, highlighting the affective scenes. Especially in dramatic scenes, the music becomes more powerful when compared to “normal” dialogue-filled scenes (seen in the scene of Figure 6). Also, the female characters’ voice-pitch gets higher as they express sadness and try to fight the urge to cry. The same happens in pornographic scenes, which are analyzed in more detail later. This can be attributed to the neurobiological mechanisms regarding affective sounds which, accompanied by the music, evoke affects of care and sadness (cf. Panksepp & Biven, 2012, pp. 187–188, 238).

The game opens by throwing the player-character into an intimate and sexualized situation. Syuji finds himself having fallen to the ground, inadvertently grabbing Yotsuko and Alice’s breasts (see Figure 7). Before this picture appears on the screen, Syuji narrates the following:

Something very unusual is going on. What is this plump softness overflowing beneath my right hand? And this small bulge, as perky as a chirping bird, under my left palm. The perfect embodiment of a guy’s fantasies rests in my right hand. It gives me a sense of security, accepting my entire being. With even the most minor movement, it bounces back softly in response. Does that mean my left hand is unhappy? Not at all. In fact, it’s experiencing complete bliss as well. There’s a faint, almost imperceptible softness hiding behind the several layers of clothing. It isn’t obvious, but it’s definitely there––a roundness the male form lacks. At the very least, I can say that it certainly isn’t losing to my right hand. I can even say it’s winning in a certain way.

With such an explicit depiction of two women’s breasts, this very first scene sets the game’s visual and thematic style right from the beginning. The three characters’ traits and visual styles are derived from the clichés of the otaku database: the tsundere (3) character is rendered visually to look like an underage girl, whereas the childhood friend—who is secretly in love with the main character, itself a trope—is rendered as more mature both in her behavior and appearance. The main character is a young and sexually inexperienced male, who ends up inadvertently hurting the female characters’ feelings. As Alice fulfills the tsundere trope, her character is characterized by expressions of shock, anger and disgust, which is accompanied by her various verbal insults towards Syuji. This can be seen in Figure 7 as she utters at Syuji: “Wh-Why you…! Get out of my face, you virgin!” This is a common line uttered by a tsundere character (see Galbraith, 2009), expressing her disgust towards the male character’s sexually charged acts or utterances, and coded as to express the affect of rage. After the scene, the events leading to this are told as a flashback.

Dating-simulation games typically feature one “correct” storyline that has a “happy” ending and multiple “wrong” storylines that feature either “bad” or “incomplete” endings (Taylor, 2007, pp. 194–195). So is the case in Newton, if one considers the game’s main goal to have a closed ending to the story. Only Alice’s storyline does this by having Syuji and Yotsuko successfully return to their time without altering the future’s scientific progress and having Alice (and Emmy) publishing the theory of universal gravitation. All other storylines have an open ending which does not resolve the main plot point of correcting the timeline, even though Syuji ends up having a relationship with each girl in a way that could be considered a “happy” ending (excluding the storyline of Lavi, which ends abruptly as Lavi drugs Syuji to prevent him altering the future, forcing him to stay with her forever).

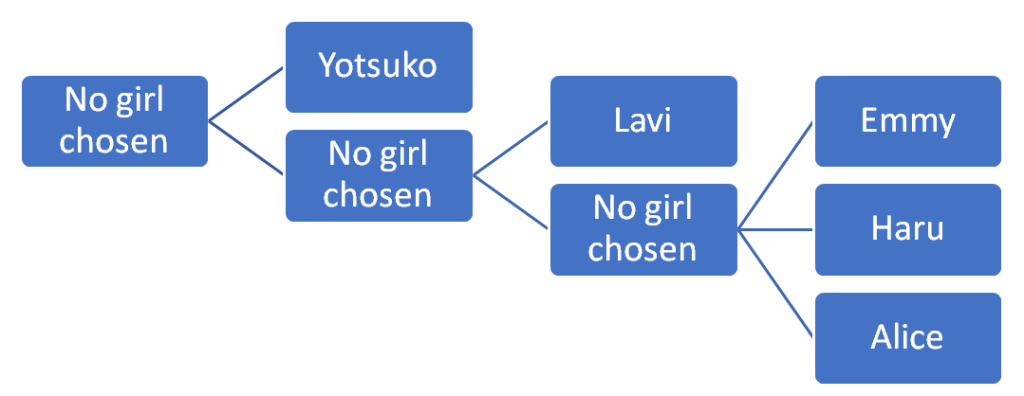

To unlock Alice’s storyline, the player must first finish Yotsuko and Lavi’s storylines (Figure 8). Upon completion, they can attempt finishing the storyline of Alice or, alternatively, Haru or Emmy. This narrative choice forces the player to witness two “bad” or incomplete endings, thus deepening narrative immersion as the total amount of playtime increases highly. If the player were able to unlock Alice’s storyline from the start, it is questionable whether one would unlock any other route. Therefore, playing through incomplete endings is nevertheless experienced as rewarding when the player finally finishes the “proper” ending.

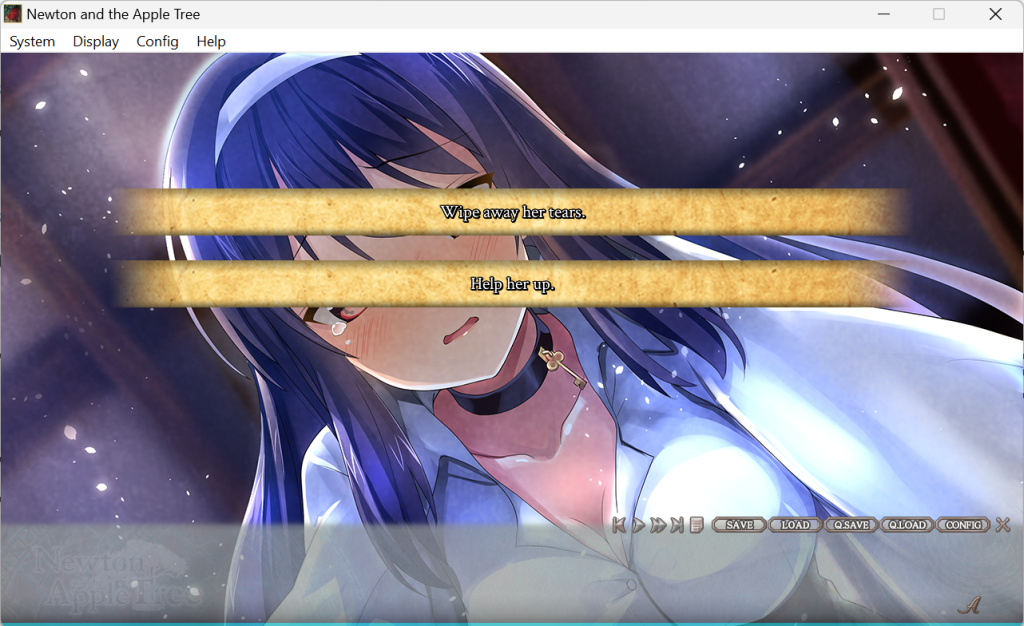

The first pornographic scene can be unlocked right after the player chooses Yotsuko’s route. The choice is the highlight of Yotsuko’s melodramatic confession about her romantic feelings for Syuji, which is accompanied by sentimental music and a close-up shot on crying Yotsuko (see Figure 9). The scene uses auditive, visual and narrative qualities in evoking the affects of sadness and care in the player. This is manifested through the emotional weight placed on the character trope of Yotsuko, accompanied by music coded to evoke sadness and the visual imagery of Yotsuko crying for the first time, coded to evoke sadness and care. The option to “wipe away her tears” results in choosing Yotsuko as Syuji’s partner, while the “help her up” option leads to other choices later in the game. When the player chooses the “wipe away her tears” option, the first pornographic scene follows (see Figure 10).

Figures 9 (left) and 10 (right): Key scenes with Yotsuko in Newton and the Apple Tree (2017).

Gradually, Syuji removes Yotsuko’s clothes, and the characters engage in sexual intercourse. The sex scenes are depicted with a couple of still images, the only animation being the movement of the eyes and lips as well as a thrusting motion. Even in the intimate sex scenes, Syuji’s character is almost completely absent. In the scenes depicted in Figures 9 and 10, Yotsuko’s eyes are either closed or slightly open. These facial expressions are coded as to evoke the affects of care and sadness accompanied by the music (cf. Panksepp & Biven, 2012, pp. 187–188, 238). The sex scenes play out according to the general conventions of eroge games and pornography in a broader sense. The auditive elements are mostly high-pitched moans and, in the dialogue, both characters express their sexual satisfaction, in most cases ending with both of them climaxing. A lot of the dialogue also features the characters expressing their mutual feelings of romantic love, conveying the affects of care and lust. The sex scenes are therefore inherently linked to the larger emotionally, romantically motivated storyline and character development.

The characters of Newton express generic narrative tropes of tsundere, cheerful maid and childhood friend who has secretly loved the main character throughout the years. They are also rendered visually in the same style according to the generic conventions of the transmedia works of Japanese popular culture. However, several of the characters’ affective qualities are manifested through coherent and plot-heavy narrative.

Newton places a lot of focus on the time-travelling story itself and its long and relatively complex plot in terms of eroge games. This indicates that the plot itself carries a strong meaning in motivating the characters and, accordingly, the affects evoked in players. As Alice’s storyline ends by having Syuji and Yotsuko travelling back to their time and Alice staying in her own time, the long narrative rewards the player with a strongly affective final scene between Syuji and Alice that carries so much weight because of the narrative depth and the characters’ feelings and motivations.

The narrative of Newton is divided into days, depicting the time Syuji and Yotsuko spend in the past. The player sees this in the save mode. After the player has chosen a storyline focusing on a particular female non-player character, the save mode is marked by the non-player character’s name instead of the days, as can be seen in Figure 11:

This is also coded as to elicit affects towards the particular character, indicating that finally the player has made a choice to commit to a certain potential romantic interest. After the player finishes a storyline, they unlock additional scenes featuring that specific female non-player character. The scenes contain additional pornographic images not featured in the main storylines. These scenes offer the player something they cannot obtain in the storylines themselves, as these scenes can be experienced only by unlocking and finishing both Alice and Emmy’s storylines. The scenes are connected to the main narrative very loosely, acting as bonus scenes.

Regarding Newton (and visual novels in general), progress time is defined as the objectively measurable time the player takes to play the game from the beginning to the end. Story time is the storyline of Syuji and Yotsuko told in chronological order, as well as combined with the other possible storylines, and world time is the story time measured in the story world’s time, that are the counting days which appear for the player during the gameplay.

On my first playthrough, I read the dialogue of the main character, which is not heard as spoken dialogue, at my own fast pace, but decided to listen to the other characters’ dialogue to pay attention to the tone of the voice acting. This led to an odd pace where I skimmed the dialogue of the main character, whereas the other characters’ dialogue processed in my mind for a longer time as I listened to them in their natural speed. Therefore, my supradiscourse featured a significantly larger portion dedicated to characters other than Syuji. I have measured the duration between the choices the player can make by utilizing the automode option set in a default mode (see Table 2). Effect here is determined as a major choice that locks the gameplay into a specific storyline. Some choices made by the player only have an effect on individual dialogue; therefore, they are not defined as having an effect on storyline.

| Hours and Minutes | Effect of Player’s Choice on Storyline | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st choice | 2.18 | No effect |

| 2nd choice | 2.29 | No effect |

| 3rd choice | 6.02 | No effect |

| 4th choice | 6.04 | No effect |

| 5th choice | 13.06 | Yotsuko’s storyline |

The first major choice that can unlock the first pornographic scene happens after over 13 hours of play in automode. Since the game requires the player to follow the story for such a long time and make several choices that ultimately have no effect on gameplay, the eventual choice carries strong affective qualities. After the first pornographic scene, others follow rapidly. This happens regardless of the storyline the player has chosen. All other storylines, except for that of Alice (the main storyline), contain two pornographic scenes, whereas Alice’s storyline contains three. This can be interpreted as emphasizing the main storyline’s affectivity as compared to the other storylines, as well as signalling the focus shifting from an incentive offered by the first pornographic scene to the fulfillment of the overall storyline. Additionally, the reward system evoked by the seeking affect is strongly conditioned to fixed temporal intervals, meaning the occurrence of other pornographic scenes in a much faster pace can be attributed to the psychological process of conditioning oneself to reward (cf. Panksepp & Biven, 2012, pp. 95–97).

The player can set the game on autoplay with the fastest speed, but by playing this way it becomes impossible to process the dialogue properly. I measured the progress time on the fastest speed (see Table 3). If chosen to play on the fastest speed, the player is incapable of processing the dialogue fully and therefore is not able to form affective bonds with the characters as if they were processing every single line of dialogue. However, even on the fastest setting it takes over an hour for the player to reach the first choice and possibly a pornographic scene. Evidently, it is very unlikely that a player would choose to play Newton solely for pornographic purposes. Furthermore, a player would not be able to form a coherent suprastory and the only affects would be evoked by quickly shifting audiovisual elements.

| Hours and Minutes | Effect of Player’s Choice on Storyline | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st choice | 0.12 | No effect |

| 2nd choice | 0.13 | No effect |

| 3rd choice | 0.34 | No effect |

| 4th choice | 0.34 | No effect |

| 5th choice | 1.14 | Yotsuko’s storyline |

Anable (2013) argues in their analysis of “casual games” that a major part of the affective processes are formed in “the spaces between.” Even though they do not explicitly talk about visual novels, this genre can sometimes be classified under the broad umbrella of “casual games” as well. One is not able to finish playing Newton in one sitting, even if they were to play at the fastest speed throughout the whole game; the player must form a longer affective relationship with the game and its characters. Games that take dozens, hundreds or even thousands of hours to finish inherently contain elements that evoke the affect of seeking in players.

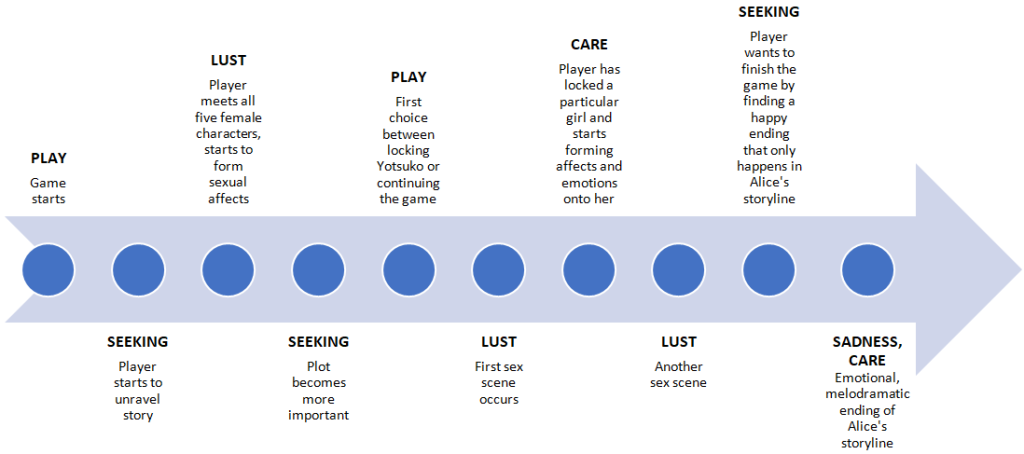

As both the progress and story time in Newton are measured in dozens of hours, the player unavoidably forms affects towards the characters during the progress time. Pornography as a genre and medium is often seen only aiming for instant gratification and mainly evoking affects of lust and play, but as Newton shows, pornography can have also other aims and evoke several affects. The game utilizes pornographic scenes also as an incentive and conditioned reward for the affects of seeking, care and lust (cf. Panksepp & Biven, 2012, pp. 91–93). As pornography is a genre that resonates bodily in the player, complementing such a strong stimulus with a long and complex narrative deepens the affectivity by evoking several different affects in the players. The affect of seeking combined with lust can form more complex emotional reactions and bonds with the characters in the player, and these emotional experiences and relationships form the basis of games as affective systems. I have demonstrated in a simplified manner the temporal occurring and evolving of the major affects during the progress time in Figure 12:

Analyzing the affects more thoroughly, as well as the ways different layers and understandings of game and play time are constructed in a more detailed manner, is out of the scope of this paper, but call for further research.

Conclusion

In the previous section, I analyzed the visual, auditive and temporal-narrative stimuli of Newton and the affects they evoke in players. These affects express the primary emotions discovered in affective neuroscience. In Table 4, these stimuli have been categorized to match with the affects evoked by the gameplay and world derived from primary emotions:

| Seeking | Rage/ Anger | Fear | Lust | Care | Panic/ Sadness | Play | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | X | X | X | X | |||

| Auditive | X | X | X | X | |||

| Temporal- narrative | X | X | X | X | X |

This simple categorization shows which affects are coded in, and expressed through, different elements of the visual novel. As Newton contains several pornographic scenes, lust is a central affect pervading the genre. Care is manifested through the elements of melodrama, affective chara-moe elements of the characters’ visual rendering and the temporal elements of forming an affective relationship with the characters after having played the game for a long time. Play is present in the medium of videogames itself, as well as certain characters’ playfulness behavior and character traits. Rage is mostly manifested through individual scenes where characters get angry and yell, accompanied by the character visual rendering. Sadness is evoked by visual rendering of the characters, as analyzed previously, auditive elements of high pitch and crying, and the narrative elements of the game, such as the ending of Alice’s storyline.

What my analysis shows is that the case study is coded to evoke all the primary emotions, excluding fear, through its fictional characters and the story world of which they are part. Additionally, the analysis also explores how these elements are coded in character rendering and sound design as well as in narrative world. It also explains how the contradictory intersection between the pornographic, incentive rewarding content and time-consuming quality of finishing the game’s several storylines to obtain the “right” and happy ending all contribute in evoking different affects, especially the affect of seeking. My analysis highlights the way the temporality of play, creates an emotional bond in the player by establishing an affective relationship with both the surrogate character of Syuji and the female non-player characters, even though the straight-forward and fast nature of pornography can at first appear to be at odds with long-term affective relationships.

The categorization suggested in the article is broad yet effective in analyzing the affects of Newton, considering its aspects of Japanese popular culture as well as temporal-narrative qualities related to other forms of videogame culture. The analysis offers a way to understand how affects are evoked in the players using a variety of stimuli, as well as providing a useful tool to analyze the formation and manifestation of affects in various art and media works. The method suggested in this article could be expanded to include different psychological or sociological frameworks to conduct a more thorough analysis of how art and media works create a complex web of affectivity. The framework should also be accompanied by audience reception studies useful to replicate the results with a variety of consumers of art and media.

The game and its fictional characters are coded to express and evoke affects in many different ways, which I have categorized. Audiovisual characteristics of the characters that fulfill the generic conventions of the transmedia continuum of Japanese popular cultures are strengthened and deepened by narrative frameworks of the fictional characters’ generic tropes derived from the otaku culture. The temporal-narrative affects are based on the story and plot of the game and generic conventions and tropes as well as play time and how the narrative unfolds. I have analyzed these temporal-narrative elements based on the progress time of the player based on the expectations created by generic conventions and tropes and the narrative elements manifested by the fictional characters.

The study shows how the affects evoked by fictional characters are rooted in primary emotions and how audiovisual, narrative and temporal qualities of fiction as well as the unique characteristics of visual novels support the construction and manifestation of these affects. As such, this article offers a case study into an often neglected, yet major, phenomenon of videogames, that is Japanese visual novels. Arguably, the proposed affective framework of primary emotions can be applied to other popular media as well as other videogame genres.

Endnotes

1. Panksepp and Biven (2012, p. 2) capitalize the primary affective systems and emotions to distinguish them from the way they are used in vernacular language and to highlight their physical and distinct networks in mammalian brains.

2. Using child-like character rendering in Japanese pornographic media is a highly controversial topic that has elicited a great deal of both academic and legislative conversation regarding the ethics of producing and consuming such work (e.g. Eelmaa, 2022; Nagayama, 2021, pp. 250–254).

3. Tsundere is a female character archetype characterized by cold, rude and possibly violent behavior towards the male main character, which is to hide the character’s insecurity and her romantic feelings towards the male main character (Galbraith, 2009).

Author Biography

Henri M. Nerg is a PhD student of Modern Culture studies at University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Their PhD research is a multi-disciplinary approach to the emotions evoked by works of transmedial popular culture based on affective neuroscience.

References

Anable, A. (2013). Casual games, time management, and the work of affect. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, 2.

https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/26293

Anable, A. (2018). Playing with feelings: Video games and affect. University of Minnesota Press.

Arjoranta, J. (2015). Narrative tools for games: Focalization, granularity, and the mode of narration in games. Games and Culture, 12(7–8), 696–717.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015596271

Azuma, H. (2009). Otaku: Japan’s database animals (J. E. Abel & S. Kono, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published in 2001)

Bacha, C. S. (2019). The first revolution: Taking Jaak Panksepp seriously: Group analysis and the neuroscience of emotion. Group Analysis, 52(4), 441–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316419858583

Blom, J. (2020, August). Your fantasies are quantified: Western perspectives on sex and sexuality in Japanese erotic games [Conference presentation]. Replaying Japan 2020, Liège Belgium. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joleen-Blom/publication/344804605_Your_Fantasies_are_Quantified_Western_Perspectives_on_Sex_and_Sexuality_in_Japanese_Erotic_Games

Brinkema, E. (2014). The forms of the affects. Duke University Press.

Cavallaro, D. (2009). Anime and the visual novel: Narrative structure, design and play at the crossroads of animation and computer games. McFarland.

Cohn, N. (2010). Japanese Visual Language: The structure of Manga. In T. Johnson-Woods (Ed.), Manga: An anthology of global and cultural perspectives (pp. 187–203). Continuum.

Davis, K. L., & Montag, C. (2019). Selected principles of Pankseppian affective neuroscience. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.01025

Eelmaa, S. (2022). Sexualization of children in deepfakes and hentai. Trames: A Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 26(2), 229–248.

Galbraith, P. W. (2009). Moe: Exploring virtual potential in post-millennial Japan. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies.

http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2009/Bryce.html

Galbraith, P. W. (2011). Bishōjo games: ‘Techno-intimacy’ and the virtually human in Japan. Game Studies, 11(2). https://gamestudies.org/1102/articles/galbraith

Galbraith, P. W. (2021). The ethics of affect: Lines and life in a Tokyo neighborhood. Stockholm University Press.

Japanese Law Criminal Code. (2020). Japanese Law Translation Database System.

Juul, J. (2013). The art of failure: An essay on the pain of playing video games. MIT Press.

Karhulahti, V. (2015). An ontological theory of narrative works: Storygame as postclassical literature. Storyworlds, 7(1), 39–73. https://doi.org/10.5250/storyworlds.7.1.0039

Lamarre, T. (2009). The anime machine: A media theory of animation. University of Minnesota Press.

Laplacian. (2017). Newton and the Apple Tree. Sol Press.

Nagayama, K. (2021). Erotic comics in Japan: An introduction to eromanga. Amsterdam University Press.

Nguyen, C. T., & Williams, B. (2020). Moral outrage porn. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 18(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.26556/jesp.v18i2.990

Okabe, T., & Pelletier-Gagnon, J. (2019). Playing with pain: The politics of Asobigokoro in Enzai Falsely Accused. Journal of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities, 4(1), 37–53. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjadh/4/1/4_37/_pdf

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J., & Biven, L. (2012). The archaeology of mind: Neuroevolutionary origins of human emotions. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pelletier-Gagnon, J., & Picard, M. (2015). Beyond rapelay: Self-regulation in the Japanese erotic video game industry. In M. Wysocki & E. W. Lauteria (Eds), Rated M for mature: Sex and sexuality in video games (pp. 28–41). Bloomsbury Academic.

Saitō, T. (2011). Beautiful fighting girl (J. Keith Vincent & D. Lawson, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

Steam. (2020). Newton and the Apple Tree. https://store.steampowered.com/app/721010/Newton_and_the_Apple_Tree/

Taylor, E. (2007). Dating-simulation games: Leisure and gaming of Japanese youth culture. Southeast Review of Asian Studies, 29, 192–208.

Tychsen, A., & Hitchens, M. (2009). Game time: Modeling and analyzing time in multiplayer and massively multiplayer games. Games and Culture 4(2), 170–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412008325479

Van der Westhuizen, D., & Solms, M. (2015). Basic emotional foundations of social dominance in relation to Panksepp’s affective taxonomy. Neuropsychoanalysis, 17(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2015.1021371

Watt, D. (2017). Reflections on the neuroscientific legacy of Jaak Panksepp (1943–2017). Neuropsychoanalysis, 19(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2017.1376549