by Samuel Poirier-Poulin

Published September 2023

Download full pdf of article here (TBC)

Abstract

This article offers a conceptualization of trauma in horror video games, and in Cry of Fear (Team Psykskallar, 2013) in particular. It argues that video games can cut across the reality/fiction divide, deeply affect the emotional organization of the player, and leave them with wounds that take time to heal—a phenomenon I call “videoludic trauma.” More specifically, it develops the idea that Cry of Fear can induce a form of trauma in the player by putting them in horrifying and intense situations. Drawing on trauma studies, bleed theory, and phenomenology, this paper first defines “videoludic trauma,” contrasts it with “positive discomfort” (Jørgensen, 2016), and introduces the concept of “horror flow.” Then, using these concepts as a starting point, it examines how Cry of Fear represents trauma symptomatology and presents four vignettes that each focuses on a specific aspect or moment in Cry of Fear that had a strong impact on my gaming experience—from the visceral combat system to the feeling of loneliness the game led me to experience. This paper provides new analytical tools and vocabulary to talk about our trauma-like experiences with video games and lays the groundwork for future research focusing on the relationship between trauma and the horror genre.

Keywords: trauma studies, horror video games, bleed, videoludic trauma, Cry of Fear

Content note: this article includes references to trauma, suicide, self-harm, murder, and child abuse.

Introduction

Originally derived from the ancient Greek “wound” or “damage” (τραῦμα), the term “trauma” has become prevalent in academia and popular culture over the last thirty years. This “contemporary trauma culture,” as Roger Luckhurst (2008, p. 2) calls it, has been shaped by scholars from numerous disciplines and by various forms of narratives and media. While Dominick LaCapra (2001) notes that “no genre or discipline ‘owns’ trauma as a problem or can provide definitive boundaries for it” (p. 96), Tobi Smethurst (2015) highlights that trauma has become a “travelling concept” (Bal, 2002) that “shapes and is shaped in turn by each theoretical context in which it is invoked” (p. 7).

According to the World Mental Health surveys, 70.4% of the world population will be exposed to a traumatic event at least once during their life, with most people first experiencing a traumatic event “in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood” (Benjet et al., 2018, p. 54). Five types of traumatic events are especially widespread across the world: “[1] witnessing death or serious injury, [2] experiencing the unexpected death of [a] loved one, [3] being mugged, [4] being in a life-threatening automobile accident, [5] and experiencing a life-threatening illness or injury” (Benjet et al., 2018, p. 54, numbering mine). Following Ronald Doctor and Frank Shiromoto (2010),

trauma and the traumatic stress disorders are conditions that arise from exposure to extraordinary life-threatening events or accumulated smaller traumas usually experienced in one’s developmental years. These conditions are marked by chronic arousal, emotional numbing, avoidance of reminders of the trauma(s), and intrusive thought or dreams related to trauma events. (p. 276)

Judith Herman (1992/2015) explains that traumatic events generally lead to a feeling of powerlessness and terror: “At the moment of trauma, the victim is rendered helpless by overwhelming force. . . . Traumatic events overwhelm the ordinary systems of care that give people a sense of control, connection, and meaning” (p. 33). As she points out, traumatic reactions occur when action is futile, when flight or resistance are impossible (p. 34). In these circumstances, the traumatic event generally leads to an altered state of consciousness (Herman, 1992/2015, p. 42) and to a reduction in the sense of agency and body ownership (Ataria, 2015). Bessel van der Kolk (2000) explains that trauma survivors have faced such horror that their conception of themselves, their capacity to cope, and their biological threat perception may be temporarily or permanently altered. Even though psychological trauma is often perceived as the result of a sudden, punctual event, it can also be the consequence of microaggressions, domestic violence, or historical events such as colonization, genocide, and slavery (Brave Heart, 2000; Brown, 1991; Moody & Lewis, 2019; Schwab, 2010).

In the humanities, trauma theory has been used to better understand the “psychological, rhetorical, and cultural significance of trauma” (Balaev, 2018, p. 360). Over the years, much has been said about this topic, leading notably to debates on the representability of trauma and the nature of memory (cf. Caruth, 1996; Gibbs, 2014) and to publications tracing the cultural history of trauma (Farrell, 1998; Luckhurst, 2008) or focusing more specifically on the use of violence in cinema to represent individual or collective traumas (Elm et al., 2014; Lowenstein, 2005). Despite the vitality of this research field, trauma theory remains marginal in game studies. So far, a few scholars have explored the use or design of games to heal personal traumas (e.g., Austin & Cooper, 2021; Danilovic, 2018; Sapach, 2020), while others have analyzed the aesthetic of trauma and the representation of traumatized game characters (e.g., Bumbalough & Henze, 2016; Kuznetsov, 2017; Rusch, 2009) or the idea that video games could generate in the player feelings of empathy, guilt, or powerlessness (e.g., Harrer, 2018, pp. 152, 156–158; Smethurst, 2015). Souvik Mukherjee and Jenna Pitchford (2010) have argued that players of multiplayer military shooters like America’s Army (United States Army, 2002) and Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (Infinity Ward, 2007) can experience some symptoms of war trauma in a milder form, including disorientation, tension, fear of injury, and pressure to protect their teammates. As they note, the player in these games moves at a slow pace to ensure their firing accuracy, thus “emulating the experience of a patrol in contemporary warfare” (Mukherjee & Pitchford, 2010, p. 43). Meanwhile, Smethurst (2015) has written about their trauma-like gaming experience with Spec Ops: The Line (Yager Development, 2012), describing how guilty they felt after firing white phosphorous, a controversial incendiary weapon, and killing dozens of civilians. The description of their gaming experience is worth quoting at length:

I was the one who had pushed the buttons and dropped the bombs. Whether or not I knew I was doing it at the time, I had a hand in murdering those civilians. I did not experience the same trauma afterwards that the protagonist did, of course, but his reactions were certainly not too far from my own. I have taken thousands upon thousands of virtual lives, but these were the first for which I truly felt that I shared the burden of guilt.

Rationally, I knew this was absurd. Afterwards I reminded myself that these were virtual civilians, not real ones; and besides, the game is programmed in such a way that if you want to finish it, you have to use the white phosphorus. . . . But none of this rationalisation changed how horrified I had felt, along with the protagonist, on discovering the charred bodies that he/we/I had produced. If trauma studies has taught me one thing, it is that fictional events can have real effects on one’s outlook and ethics. . . . The fact that I felt the need to rationalise my guilt over Spec Ops: The Line in the first place demonstrated just how “real” of an effect the game had had on me. (Smethurst, 2015, p. viii, emphasis in the original)

As noted by Luckhurst (2008), trauma seems to be “worryingly transmissible: it leaks between mental and physical symptoms, between patients . . . between patients and doctors . . . and between victims and their listeners or viewers” (p. 3). Drawing on horror studies and using the video game Cry of Fear (Team Psykskallar, 2013) as a case study, this paper suggests that some video games can induce a form of trauma in the player by putting them in horrifying and deeply intense situations. While several horror games successfully generate fear and anxiety, what the player experiences in Cry of Fear goes further and is closer to a form of trauma; I call it “videoludic trauma.” I see videoludic trauma as the result of a disruptive gaming experience that cuts across the reality/fiction divide, deeply affects the emotional organization of the player, and leaves them with wounds that take time to heal.

In her foundational book Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing (1997), Isabel Cristina Pinedo argues that the horror film is temporally and spatially finite: it promises a “contained experience” and an imaginary one, with the screen marking off a “bounded reality” (pp. 41–42). In game studies, this perspective has been taken up by Bernard Perron (2005, 2018), who writes that horror video games offer a “bounded experience of fear” (Pinedo, 1997, p. 5, as cited in Perron, 2005, para. 7; 2018, p. 87) and push us “to play at frightening ourselves” (Perron, 2005, para. 27). In this paper, I question the idea that the player is sheltered from what occurs onscreen and the assumption that the boundary between the universe of the player and the universe of the game is clearly delineated. My work is based on the idea that video games can leave the player with strong impressions that continue to resonate in them long after the gaming session is over (Tronstad, 2018). Building on trauma studies, bleed theory, and phenomenology, this paper first defines videoludic trauma, contrasts it with “positive discomfort” (Jørgensen, 2016), and introduces the concept of “horror flow.” Then, using these concepts as a starting point, it examines how Cry of Fear represents trauma symptomatology and presents four vignettes that each focuses on a specific aspect or moment in Cry of Fear that had a strong impact on my gaming experience—from the visceral combat system to the feeling of loneliness the game led me to experience.

As highlighted by Torill Elvira Mortensen and Kristine Jørgensen (2020), research on video games with transgressive content has historically followed the tradition of media effects research (p. 6). This has led to a lack of vocabulary to discuss and analyze these games, and to discussions that centre on their problematic nature rather than on their potential to be “aesthetically provocative and transformative” (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, p. 6). This paper thus seeks to provide new analytical tools and vocabulary to talk about our trauma-like experiences with video games and lays the groundwork for future research focusing on the relationship between trauma and the horror genre.

Toward a Conceptualization of Videoludic Trauma

In the following pages, I seek to conceptualize videoludic trauma from an aesthetic perspective. I see trauma as a spectrum and aim to distance myself from the binary opposition “traumatized/not traumatized.” My work starts from the premise that all sad or tragic events have some shades of trauma—from being around death or illness, to suffering from loneliness or wondering about the meaning of life. On the one hand, I recognize that games affect people differently and that one’s life trajectory, vulnerability, and previous gaming experiences influence the way they experience videoludic trauma (if they experience it at all). On the other hand, I stress that games which induce videoludic trauma tend to have similar goals and formal properties: they seek to generate deep emotions and break with certain social norms or genre conventions. These games can be situated within the larger corpus of transgressive games, defined by Mortensen and Jørgensen (2020) as games that challenge the sensibility of the player, create a sense of discomfort, and put into question the player’s willingness to play or keep playing these games (pp. 27, 80). Games that address heavy topics such as suicide, depression, loneliness, or war are arguably more likely to produce negative feelings in the player and create a trauma-like experience.

In Writing History, Writing Trauma (2001), LaCapra identifies two types of response to trauma narratives: “empathic unsettlement” and “unchecked identification.” According to LaCapra, empathic unsettlement happens when the reader feels empathy for the trauma survivor by bringing in their own experiences and points of view, thereby avoiding taking the place of the survivor and reliving their trauma (pp. 40–41, 78). Conversely, unchecked identification occurs when the reader identifies with the survivor so strongly that there is a confusion between the self and the other; the reader ends up incorporating in themselves the traumatic experience without critically reflecting on it, leading in some instances to the transmission of a secondary trauma (LaCapra, 2001, p. 28). LaCapra creates a clear hierarchy between these two responses and argues that empathic unsettlement is both the response the reader should seek to experience and the response the writer should seek to evoke in the reader (p. 41).

Although LaCapra’s (2001) reading strategies are useful for researchers who work on trauma and know beforehand what to expect from certain texts, this dichotomy hardly represents the nuanced aesthetic experience many players have with video games (or with fiction in general). As highlighted by Mortensen and Jørgensen (2020), we tend to accept uncomfortable or even taboo content when we encounter it in a game because we see it as part of an aesthetic experience (p. 4). Our default reaction is to engage with transgressive games, to the point sometimes of lowering our defence mechanisms, “opening” our bodies and putting ourselves in a vulnerable position to fully experience what these games have to offer us. This in turn facilitates the creation of videoludic trauma. While we know that some games can overwhelm us, we might hope that they will be awe-inspiring, allow us to experience the sublime, or produce feelings that will surpass the negative feelings we first come to experience (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, p. 4). In addition, while we tend to think of play as something safe because we can always stop playing a game that would become too disturbing, I would highlight that one might realize that a game goes too far only once they have already experienced videoludic trauma. A game like Spec Ops pushes the player to make highly questionable decisions and only let them see the horrendous consequences of their actions once it is too late. A player might also find a game segment to be profoundly transgressive only after thinking about it more deeply (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, p. 139), following what could be interpreted as a period of latency.1

LaCapra’s (2001) concerns about over-identification with trauma survivors are somewhat reminiscent of the violent video game debate and the fear that players would so strongly identify with the protagonists of violent games that they would reproduce their behaviour and become more violent. As Smethurst (2015, p. 14) observes, LaCapra’s stance further contrasts with the discourse of many game designers who seek to produce an immersive experience and encourage players to identify with the game characters and the game world. Of particular interest to my conceptualization of videoludic trauma is how this identification process has been theorized in Nordic live action role-playing (LARP), which is known for its games specifically designed to generate bleed. As Sarah Lynne Bowman (2013) explains, bleed consists in “the blurring of the emotions, thoughts, physical state, and relationship dynamics of the player and the character” (4:05), leading to a reduction of the boundary between reality and fiction. Bleed causes a spillover between two frames of reference, with feelings like guilt, animosity, friendship, or love moving from one frame to another, and at times confusing the player (Bowman, 2013). Markus Montola (2011) conceives play as an activity surrounded by an interaction membrane through which bleed can occur and sees bleed play as a negotiation between safe and raw experiences. Bleed design is a powerful way to weaken the protective membrane of play, explore deep emotions, produce intense experiences, and make play feel more dangerous (Montola, 2011).

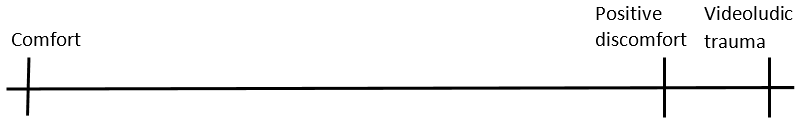

In Nordic research communities, scholars have generally used the term “positive negative experience” (Bjørkelo, 2018; Hopeametsä, 2008; Montola, 2011) or “positive discomfort” (Bjørkelo & Jørgensen, 2018; Jørgensen, 2016; Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, p. 72) to describe experiences with games that are not fun nor pleasurable, but that are still meaningful and provide in retrospect some satisfaction to the player. These terms, however, do not capture the experience I want to describe in this research. They emphasize that a game can be gratifying, even cathartic, despite being distressing and leading to uncomfortable moments. These terms underline the positive rather than the negative or hurtful aspect of the experience and typically imply that such experiences can help players to learn something about themselves. For example, Heidi Hopeametsä (2008) writes that “the player debriefs testify that the game was an intensive, claustrophobic and distressing experience, but also an experience that the players considered a remarkably good one, and one from which they have learned many positive things” (p. 197). Similarly, Montola (2011) observes that “such discomfort was considered a somewhat scary, but not an unpleasant thing. Many players considered them, at least implicitly, as desirable indicators of a powerful experience” (p. 228). While the terms “positive negative experience” and “positive discomfort” work in the context of these articles, I believe that we also need a term to describe an experience that is mostly (or wholly) negative and even hurtful; the term “videoludic trauma” allows me to describe such experiences. In addition, this term allows me to put my work in dialogue with the rich field of trauma studies and use some of the insights provided by research in this field. The term “videoludic trauma” ultimately allows me to keep focus on a series of events and experiences that must be understood together in the formation of a trauma.

In a certain way, videoludic trauma can be seen as a form of positive discomfort that has gone too far. It is the result of an experience that overwhelms the player, does them violence, and leaves them with wounds that take time to heal. Videoludic trauma can be put in dialogue with “real horror,” defined by Robert Solomon (2004) as an “an extremely unpleasant and even traumatizing emotional experience that renders the subject (victim) helpless and violates his or her most rudimentary expectations about the world” (p. 129). Horror is an emotion that leaves us “aghast, frozen in place,” and whose effects are wholly negative (Solomon, 2004, p. 117). Whereas positive discomfort falls within “transgressive aesthetics,” i.e., “an artistic practice of intentional disturbance” that “mitigate[s] transgression and increase[s] our threshold for tolerance” (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, pp. 13, 194), videoludic trauma occurs when boundaries are overstepped and when a game segment challenges what the player is willing to endure and engage with. It is thus closer to Mortensen and Jørgensen’s (2020) description of a “profound transgression” (pp. 4, 194). Videoludic trauma arguably has more transformative power than positive discomfort and might provide the player with a better understanding of a certain situation, but it becomes costly for them on the long term. Videoludic trauma is more intrusive, stays with the player, and can hardly be healed by a cathartic experience; in fact, catharsis does not seem to be possible due to its presence. While videoludic trauma can be a one-time experience that someone seeks because of the thrill it generates, videoludic trauma is so negative that players usually do not want to experience such feelings.

That being said, it is important to acknowledge here the challenge of theorizing videoludic trauma while respecting the experience of real trauma survivors. In her work on Holocaust culture in the United States, Anne Rothe (2011) has raised some concerns regarding trauma narratives and the “appropriation of the pain of others” (p. 20). She stresses that it is “empirically unsustainable” and “epistemologically impossible” to experience in an unmediated way the trauma of someone else in its totality (Rothe, 2011, p. 162). Several games that can induce videoludic trauma contain traumatized protagonists, and I wish to emphasize that videoludic trauma is not the same as the trauma of these characters, but a new experience of trauma that is the product of the interaction between the player, the game protagonist, and the game world.

In A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames (2018), Brendan Keogh offers a conceptualization of this tripartite relationship that can be used to further reflect on videoludic trauma and expand bleed theory. Keogh proposes the concept of “co-attentiveness” to describe how the player can feel immersed into a fictional world without ever forgetting that they exist in the “real” world (pp. 13–14). As he highlights, playing a video game requires “a multitude of worlds and a multitude of bodies” (Keogh, 2018, p. 3), and our embodiment as a player and as a fictional character is distributed across two realities (pp. 4–5), it is formed “across bodies and worlds” (Keogh, 2018, p. 8). For Keogh, immersion is never total: the player does not fully step into a new body nor into a new world, but peers into the game, pokes around, and only partially becomes the character (pp. 2, 199). Game play is thus “a play of bodies that alters, distributes, enhances, restricts, and skews embodied perception to partially and imperfectly embody other presences and contexts” (Keogh, 2018, p. 199, emphasis in the original). This conception of immersion and embodiment allow us to explain, at least to some extent, why the player can feel at times some of the effects of the game character’s trauma, but also feel that their trauma-like experience is the result of their interaction with the fictional world as a whole and what they go through while playing the game.

I would thus argue that videoludic trauma can be explained by two dynamics: (1) it can be transmitted from the traumatized protagonist to the player; and/or (2) it can be induced by the game as a whole in the player. The first dynamic has already been explored by bleed theory (even though the term “trauma” is not generally used) and can be seen as a form of secondary trauma. The second dynamic, though, has not been as discussed, and I would like to spend more time elaborating on it. As Smethurst (2015) writes, the trauma experienced by the player in the puzzle-platform game Limbo (Playdead, 2010) is hardly the trauma of the game protagonist; in fact, the protagonist does not seem to experience any trauma in that game (p. 124). The trauma comes from the general atmosphere of the game (its bleak black and white graphics, the absence of non-diegetic background music) and the kind of response the game generates in the player (hypervigilance, oversensitivity), who wants to avoid the grisly deaths of the character (Smethurst, 2015, pp. 124–131). The idea that trauma could be transmitted from a traumatized protagonist to the player seems especially appropriate for games where the protagonist is important to the story (where they are more than an empty shell) and where the player develops a strong relationship with them. In other instances, it seems more appropriate to interpret bleed in a broader sense: in games like Limbo, bleed does not blur the boundary between the life of the player and that of the character, but between the life of the player and what happens in the game world at large. Video games open up a “new sensorium” and afford the player a “specific experience of spatiality, temporality, speed, graphics, audio, and procedural activity” (Jagoda, 2013, p. 748). As James Newman (2002) suggests, when playing video games, the player might not see themselves as the character they play but might rather relate to the game as a whole, to “the sum of every force and influence that comprises the game” (“Thinking,” para. 2). In the case of horror video games, game designers use all the means at their disposal (narrative, visuals, sound, cutscenes, artificial intelligence, etc.) to create a specific atmosphere and generate fear and anxiety; the entire game affects the player. The aesthetic experience that results from playing video games ultimately needs to be examined from a holistic perspective, and we need to take into account the fact that trauma is not only transmissible, but that it can also be induced by a game. A game like Cry of Fear shows that these two dynamics can take place within the same game, as will become clear later in my analysis of the game.

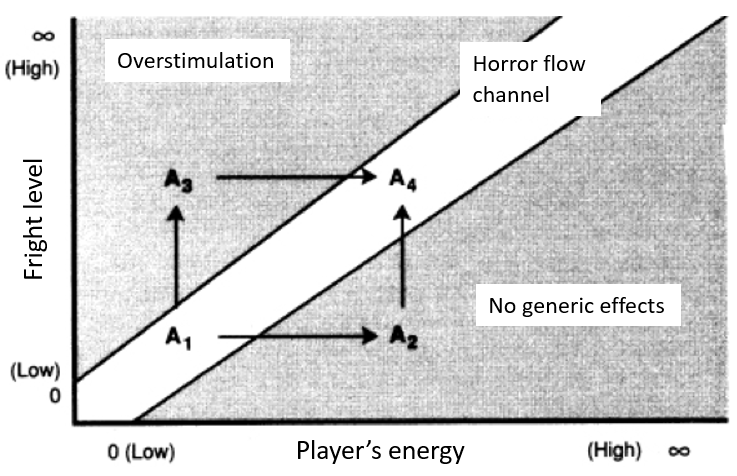

Lastly, drawing on Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi’s (1990/2008) foundational theory of flow, I wish to introduce the concept of “horror flow” and use it to contrast my experience playing Cry of Fear with that of playing other horror games. According to Csíkszentmihályi, flow occurs in situations where there is a fine balance between someone’s skills and the challenges at hand, resulting in an optimal experience (p. 71). Challenges that are too high for the skills of the participant will generate frustration, and challenges that are too low will lead to boredom. In contrast, a fine balance between skills and challenges creates the “flow channel,” where the participant is deeply concentrated on the activity for its own sake and loses the sense of time and space (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990/2008, pp. 71, 74–75). In the case of horror video games, the balance between challenges and skills influences the experience of the player, but two elements that might have a greater impact are the player’s energy and the fright level of a game. If the player is constantly frightened, playing the game will ask them to invest a lot of energy and will quickly become draining, and if the player is not frightened enough, the game will lose its generic effects and will not allow for the expected experience. Horror flow happens when there is a fine balance between the player’s energy and the fright level of the game. In the “horror flow channel,” the player is anxious and frightened while still being able to play the game without becoming too easily exhausted—fear is bearable—and gets some satisfaction from this experience (see Figure 1). This feeling is comparable to that of flow in the sense that the player is absorbed by the game, but the emotions felt are intimately related to the world of horror video games. I would argue that in the case of Cry of Fear, I was not able to reach the state of horror flow because I was overstimulated.

Figure 1: Horror flow. Adapted from Csíkszentmihályi (1990/2008, p. 74) by the author.

To be clear, my goal here is not to classify games based on whether they lead the player to experience positive discomfort or videoludic trauma, but to introduce additional vocabulary that can help us talk about our disturbing experiences with certain video games. These experiences are deeply personal, and what generates positive discomfort for someone might lead to videoludic trauma for someone else. In my case, games like Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010), Beyond: Two Souls (Quantic Dream, 2013), and especially Papers, Please (Pope and 3909 LLC, 2013) led me to experience positive discomfort. On the other hand, my experience with Cry of Fear was at times hurtful and closer to a form of trauma. I see positive discomfort and videoludic trauma as two experiences on the same spectrum (see Figure 2), and in the case of horror games, I propose to analyze videoludic trauma in relation to horror flow. An overwhelming amount of horror and shock that uses a wide register of fear- and anxiety-inducing tactics will be “too much” for the player to contemplate a game as an aesthetic object. In such cases, the player does not reach the state of horror flow, and an experience that felt within positive discomfort and was relatively safe risks becoming hurtful. Following on from this overview of my theoretical framework, the next section presents my methodology before moving to a detailed analysis of Cry of Fear.

Figure 2: Positive discomfort and videoludic trauma. Designed by the author.

Methodology

My analysis is informed by Louise Rosenblatt’s (1986; see also Rosenblatt, 1978) work on the reading process and draws on the transactional theory she developed from the 1930s onward. According to Rosenblatt, the meaning of a text does not lie in the text nor in the reader, but in the exchange (the “transaction”) between the two. Like Rosenblatt, I see reading as “a transactional process that goes on between a particular reader and a particular text at a particular time, and under particular circumstances” (1986, p. 123). Each individual brings into the reading act their backgrounds, emotions, knowledge, and expectations, and therefore, the meaning of a text varies with the reader (Rosenblatt, 1986). My analysis builds on Rosenblatt’s call to adopt a predominantly aesthetic stance and to “focus attention on what is being lived through in relation to the text during the reading event” (1986, p. 124, emphasis in the original)—or in my case, during the playing event. She contrasts this stance with a mainly efferent stance, where “the focus of attention is predominantly on what is to be retained after the reading” (1986, p. 124, emphasis in the original)—this is the stance traditionally encouraged at school. As she explains, someone else can summarize a text for us, but no one can experience its aesthetic evocation for us; the aesthetic reading is personal to each one of us. Nevertheless, even though Rosenblatt is often seen as a predecessor to reader-response theory, it is important to highlight that transactional theory does not seek to give full powers to the reader at the expense of the text. It is more accurate to say that it encourages the reader to pay attention to the multiple details of a text while allowing the reader to become an active producer of interpretations—it accommodates their subjectivity and recognizes their agency.

Although Rosenblatt’s (1978, 1986) transactional theory was originally developed to study literature, this theory can be put in dialogue with the work of many game scholars who recognize the expressive and personal nature of play. Miguel Sicart (2011), for example, acknowledges that games contain meanings, but stresses that play also includes the values, politics, and body of the player. Along the same lines, Stephanie Jennings (2018) has developed a theory of “situated play,” describing play as “an appropriative activity that is situated in subjectivity, identity, and experience” (p. 160). Her approach highlights the importance of taking into account how players generate knowledge, come to adopt certain play styles, and incorporate their subjectivity into the playing event. Lastly, my analysis is informed by the principle of “existential inquiry,” as defined by Michał Kłosiński (2022), which “focuses on the transformative functions of digital games” and “makes interpretation into a process invested in describing the metamorphosis of the subjectivity, existence and identity of the researcher as a player” (section 9, para. 1; see also Gualeni & Vella, 2020). Videoludic trauma is a highly personal, experiential, and affective area of inquiry, and studying it demands such reflective methods where the situated and embodied experience of the player is taken into account.

Introducing Cry of Fear

Cry of Fear was originally developed as a mod for Half-Life (Valve, 1998) by Team Psykskallar, an independent Swedish studio. It was released as a standalone game in 2013 and can now be downloaded for free on Steam. The game tells the story of Simon Henriksson, a young man who wakes up in an alley and must find his way back home after a man intentionally ran over him with a car. As the player progresses in the game, they discover that Simon lost the use of his legs following the attack and that the game is a metaphorical depiction of his trauma and his fight against his inner demons. Cry of Fear generally follows the conventions of the survival horror subgenre and requires the player to fight against monsters, solve puzzles, and manage their inventory. The game is noteworthy for its extremely graphic scenes, its disorienting soundtrack, its first-person melee combat, and its monsters with fast and jerky movements—a sharp contrast with more traditional survival horror games in which monsters are much slower.2 Based on my own experience, I would argue that Cry of Fear induces videoludic trauma in the player through its shocking and overwhelming environment and through a morbid reflection on solitude and suicide that reflects Simon’s existential angst. My analysis is structured around the idea that Cry of Fear explores the sensitive boundary between positive discomfort and videoludic trauma, tempting players who are drawn toward “extreme horror” but simultaneously putting them in danger of being overwhelmed and getting hurt.

Part of the experience of Cry of Fear consists in searching for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world. As Sonya Andermahr (2013) observes about literature,

the so-called trauma plot revolves around a delayed central secret whose revelation then retrospectively rewrites the narrative. The trauma novel typically presents a model of history which coincides with the idea of traumatic occlusion and the belated recovery of memory. (p. 15)

The player notably learns about Simon’s true physical and psychological condition through his psychiatrist, Doctor Purnell, who describes Simon’s trauma in a segment of the game that takes the form of a flashback:

He always goes back to the same place, day after day, just watching it like it was yesterday. Despite the fact that it causes him tremendous anxiety, he insists on returning. He insists it’s for “therapeutic” reasons, but I remain skeptical. He doesn’t respond well to questions about his personal life, and became extremely angry when I mentioned events prior to what he insists on describing as “the black day.” His school and home-life are no-go topics when discussing these feelings and anxieties. He told me the other day that he’d been seeing hallucinations, but couldn’t give a clear description of what he’d been seeing.

While Simon already suffered from loneliness before the attack, he has now become reclusive and spiteful of his life, and struggles to open up. The fact that he refers to the day of the attack as “the black day” highlights the profound impact it had (and still has) on him and how it created a clear rupture in his life.

Simon’s disability is progressively revealed in the game through a certain fascination with his lower body parts. In a nightmare sequence at the end of the second chapter, for example, the player must go through corridors filled with dozens of hands trying to grab Simon’s feet (see Figure 3). The hands deal a lot of damage to the player, forcing them to run, jump, and self-inject morphine to avoid dying while hearing Simon’s cries of pain at the same time. Following this powerful segment, Simon has a flashback to the scene where he was struck by the car. He sees the fire truck and police cars, and hears the sirens and the police radio. Later in the game, Simon must find a rotten foot and put it in a briefcase in which “I WANT MY FEET BACK” is written in blood (see Figure 4). These sequences often lead Simon to question his mental health and to emphasize his need to get help: “Damn it! What was that? Hallucinations? Am I going insane? Shit! I need to get some help, or at least… find my way back home.” At first, Simon’s urge to get help can be explained by the fact that the city is filled with monsters, but once the trauma narrative is revealed, it takes on a deeper meaning and reflects Simon’s need for help to cope with his trauma.

Figure 3: Dozens of hands are trying to hurt me. Screenshot by the author.

Figure 4: Solving an eerie puzzle. Screenshot by the author.

In addition, several monsters in Cry of Fear are symptomatic of Simon’s trauma and are part of the environmental storytelling of the game, complementing the narrative cutscenes. Writing about psychological horror, Isabella van Elferen (2015) notes that external horror often reveals the internal trauma of game characters (p. 238). Simon’s trauma is best represented by Sawrunner, a very fast and practically invincible enemy who chases the player in five segments of the game. Like how trauma resurfaces every now and then, haunting trauma survivors, this monster constantly reappears, haunting the player with its disturbing appearance, distinctive scream, and the sound of its chainsaw. In his speculative work, Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920/1961), Sigmund Freud provides a fascinating conceptualization of trauma that can be put in parallel with Sawrunner. As Luckhurst (2008) explains,

Freud envisaged the mind as a single cell with an outer membrane that does the work of filtering material from the outside world, processing nutrients, repelling toxins, and retaining the integrity of its borders—just as the conscious mind did. A traumatic event is something unprecedented that blasts open the membrane and floods the cell with foreign matter, leaving the cell overwhelmed and trying to repair the damage. (p. 9)

Following Freud’s (1920/1961) work, Sawrunner can be read as the external stimuli “powerful enough to break through the protective shield” (p. 23) of Simon’s psyche, causing Simon’s traumatic memories to come back. This monster first appears in a cutscene, violently destroying a door, and will instantly kill Simon if it manages to catch him. Sawrunner is overwhelming—the instant it appears, it becomes the player’s centre of attention—and the only viable option in the game is to run away from it, seeking to dispose of these harmful stimuli. Encounters with this monster are extremely tense, often forcing the player to move quickly in maze-like environments, and almost instantly trigger a feeling of panic in the player, somewhat representing Simon’s anxiety issues. Other monsters in the game are reflective of Simon’s struggles to come to terms with his disability or can be read as a manifestation of Simon’s suicidal thoughts: Sawer, the first boss of the game, can instantly kill Simon by slicing him at the waist, cutting off his legs from the rest of his body; Carcass, the third boss of the game, is restrained to a chair, representing Simon’s feeling of being trapped in a wheelchair; the Drowned can push Simon to shoot himself (the player must left-click on the mouse several times to “resist the suicidal influence”); and the Hanger hangs itself above the player, falling on them and injuring them.

Overall, the environment of Cry of Fear contains several clues about Simon’s struggles and highlights how helpless he feels. The streets are filled with broken police cars, and dialling 1-1-2 or 9-1-1 with Simon’s phone results in hearing someone being murdered rather than getting any help. Most doors in the game are locked (the player will never be able to open them), which conveys the idea that Simon is stuck in a nightmare with no way out. Throughout the game, it is also heavily implied that Simon harmed himself or attempted suicide. The player can notably see cutting marks on Simon’s left wrist every time they self-inject morphine to recover health. In the second chapter, the player must call a suicide hotline to get the code to open a door, whereas a banner in the train at the beginning of the sixth chapter reads in Swedish: “SUICIDE / KILL YOURSELF LIKE HELL” (my translation).3 References to suicide can be found every now and then, as if lurking in the dark corners of Simon’s mind. Simon ultimately feels that the world is against him. This is strongly illustrated through his relationship with Doctor Purnell, who is framed as the main antagonist of the game but whom the player must trust in the sixth chapter in order to get the “good” ending (in one specific segment, the player must choose between accepting or refusing to give Doctor Purnell a gun; giving him the gun is the only way to get the best of the four possible endings). It is only once the game is over that it is made clear that Purnell is not the antagonist he seems to be.

Although the game narrative and the visual depiction of Simon’s trauma might not induce videoludic trauma in the player, they are a strong foundation on top of which the gameplay takes place. Through four vignettes, I will analyze in the remainder of this paper key aspects or moments in Cry of Fear that led me to experience videoludic trauma. I wrote these vignettes mostly in the first person since they are related to my affective and sensory experience and how I progressively made sense of the game. The first two vignettes present further scholarship and consist of formalist analysis of Cry of Fear, while the two last vignettes are detailed analyses of two key segments of the game and are more autoethnographic.

Traumatic Gameplay: Four Vignettes

Disorienting Soundtrack and Absence of Audiovisual Forewarning

Writing about films, Carl Plantinga (2009) explains that music carries meaning and an affective charge that influences the experience of the spectator (p. 130). Music prefocuses or intensifies emotional responses, he says, and suggests the emotional valence of a scene (pp. 130, 134–135). In the case of video games, one can notably think of the calm musical theme of the save rooms in the Resident Evil series (Capcom, 1996–present), which indicates to the player that they are in safety, or the stressful music that plays whenever Scissorman appears in Clock Tower (Human Entertainment, 1995), making the scene more tense and informing the player of the presence of a threat. As Zach Whalen (2004) highlights, video games “rely on important cognitive associations between types of music and interpretations of causality, physicality and character” (“Conclusion,” para. 3). Music ultimately helps the player to navigate the game space (Whalen, 2004).

Cry of Fear plays with this more conventional use of music, relying on a broken causality to veil aural cues and immerse the player into a universe of “un-knowledge” (Kromand, 2008, p. 18). For example, the third chapter of the game starts with comforting music and gave me the impression that I was safely exploring the city following a boss fight and a disturbing nightmare sequence. I also got this impression in the seventh chapter, when I finally reached Simon’s hometown and explored his colourful neighbourhood while hearing birds singing. In both cases, it took less than two minutes before I got attacked again: in the first case, the comforting music stopped once the first monster, hidden behind a minivan, screamed and attacked me; in the second one, the birds kept singing despite the sudden presence of monsters. This pattern is repeated a few times in the game, but not enough for the player to get used to it. In so doing, Cry of Fear displaces the “safety state/danger state binary” (Whalen, 2004, “Conclusion,” para. 1) to confuse the player, leading them to interpret the game cues in the wrong way and unconsciously influencing their concentration and their action readiness. Music and sound become a way to reflect the psychological destabilization of the protagonist and to extend it to the player (Van Elferen, 2015, p. 227).

The game is also characterized by the absence of a warning system that would inform the player of the presence of enemies nearby. As Perron (2004) observes, warning systems have taken different forms in survival horror games: in Silent Hill (Team Silent, 1999), the radio of the protagonist emits white noise whenever an enemy is nearby, whereas in Fatal Frame (Tecmo, 2001), the filament at the lower right corner of the screen glows orange. Other games like Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) do not contain a warning system but warn the player through offscreen sounds, such as the moaning of zombies and the sound of their footsteps (Perron, 2004). While Perron sees forewarning as a way to build suspense and intensify emotional reactions, I would point out that forewarning makes survival horror games more bearable. It allows the player to get ready to face a threat and deduce when exploring can be done in relative safety and in a way that is less draining. Forewarning allows the player to be more in control; it helps them to manage their energy and reach the state of horror flow previously described.

In contrast, the absence of a warning system and the quasi-absence of offscreen sounds in Cry of Fear made me feel constantly threatened—to the point of paranoia—and led me to always be on edge. Sound effects in Cry of Fear are usually heard at the same time or after a threat appears onscreen, which made it often too late for me to react effectively. Two monsters particularly affected me: the Faster, who generally appears by destroying a door in front of the player and starts screaming only a few seconds later, and the Hanger, who screams while falling to its death on the player. It was hard for me to know when an enemy would appear, and considering that most of them were quiet and/or very fast, I only had a limited amount of time to react once I had detected their presence. This was emphasized by the design of the game environment and, in particular, the abundance of narrow perpendicular corridors, which makes it hard for the player to see enemies from afar. In these instances, sound was not used “to agitate a tingling sense in anticipation of the need to act” (Krzywinska, 2002, p. 23), but to generate jump scares. As noted by Van Elferen (2015), this sort of game design pushes the player to rely on their own insights instead of those of the game; at the same time, as the player progresses in the game and gets more and more affected by its disturbing content, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to think clearly (p. 237).

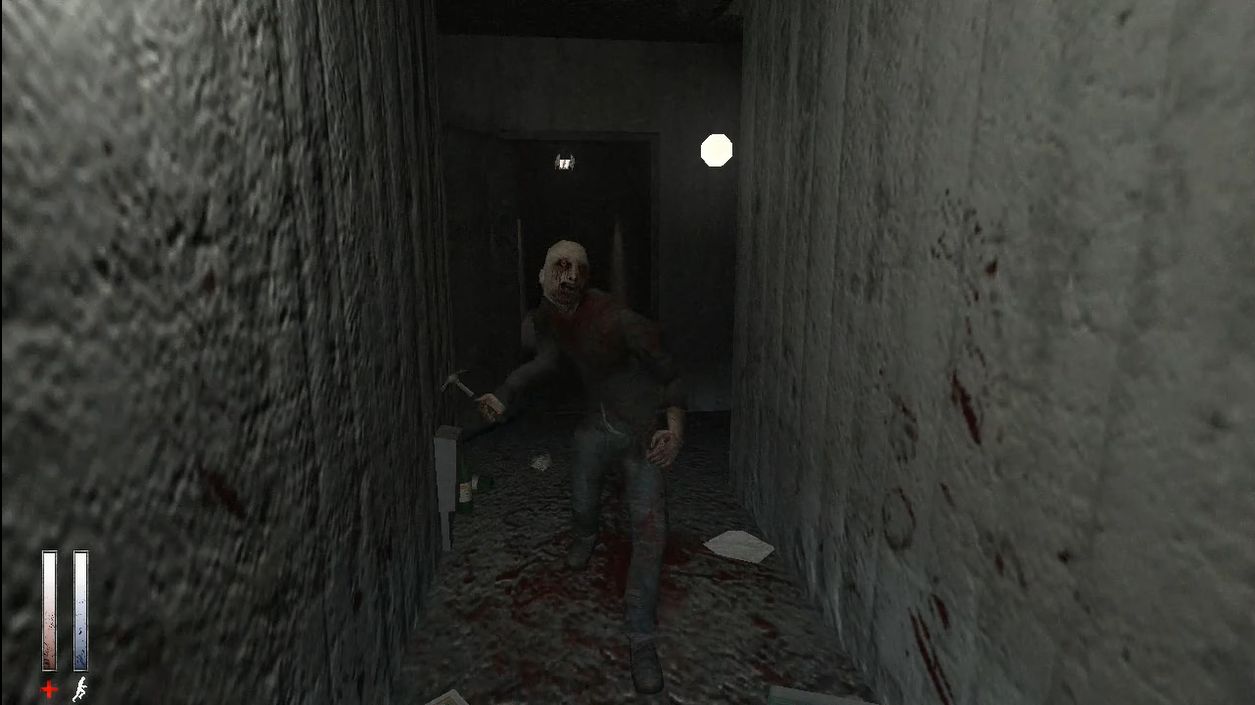

Fighting in the First Person

Like many survival horror games, Cry of Fear is characterized by limited offensive resources, and in order to save ammunition, I ended up using melee weapons several times in the game. The combination of a gameplay in the first person with the need to use melee weapons made encounters with monsters more visceral. As noted by Tanya Krzywinska (2002), the first-person perspective brings the player closer to the horror and reinforces the illusion that it is the player who is being attacked and not an “abstracted virtual self” (p. 19). Perron (2018) adds that games in the first person lead the player to touch with their eyes—to sense texture when they get close to certain objects and to feel touched when their gaze is stricken or assaulted (p. 273).

In the case of Cry of Fear, these observations apply especially well to encounters with the Slower, the most common enemy of the game, who attacks the player with a hammer (see Figure 5). I could not help but be constantly repulsed by this monster and be particularly disturbed by the idea of getting hit by a hammer, as if I could feel through my body this hammer striking Simon and crushing his bones. Angela Ndalianis (2012) describes this situation well: “the mental, psychological and sensory impact on the bodies of the characters who suffer at the hands of the monsters are not only depicted explicitly but this trauma also thrusts itself on the body of the spectator” (p. 23). The senses here become a way to experience the fear, disgust, and trauma of the protagonist and understand the ideological issues of the game (Ndalianis, 2012, pp. 23, 39).4

Figure 5: First encounter with a Slower. Screenshot by the author.

In contrast with games from the Resident Evil or Fatal Frame series (Koei Tecmo, 2001–present), in which I can respectively focus on getting a headshot and instantly killing a zombie, or taking a Fatal Frame shot and inflicting more damage to a ghost, Cry of Fear did not allow me to channel my fear into this kind of action to stay calm. During melee fights, I had to use my stamina to dodge attacks, which made the fights more “physical” and created a strong sense of presence. This combat system led to a constant oscillation between attacking and being attacked—to a feeling of always being “in the action”—and to fighting sequences that were more stressful and draining. This impression was reinforced by the narrow corridors that limited my movements, and the presence of monsters with movements that were fast and jerky, and that were thus often surprising and hard to anticipate.

The combination of this combat system with the audio elements analyzed in the previous vignette generated what James Ash (2013) has called an “intense space,” i.e., a space that captivates the player and pushes them to become attuned to the game environment. To survive the horror, I constantly felt the need to open my body to visual and auditory feedback, concentrate, and be ready to pick out any relevant detail from my environment, hence putting myself in a position of affective vulnerability (Ash, 2013). This intense space quickly became exhausting, led me to be hypervigilant and oversensitive, and facilitated the creation of videoludic trauma through the senses. Making it to the end of the game meant enduring an oppressive atmosphere for several hours, in a constant state of worry. This did not allow me to reach the state of horror flow and instead provoked an experience that was overwhelming and hurtful.

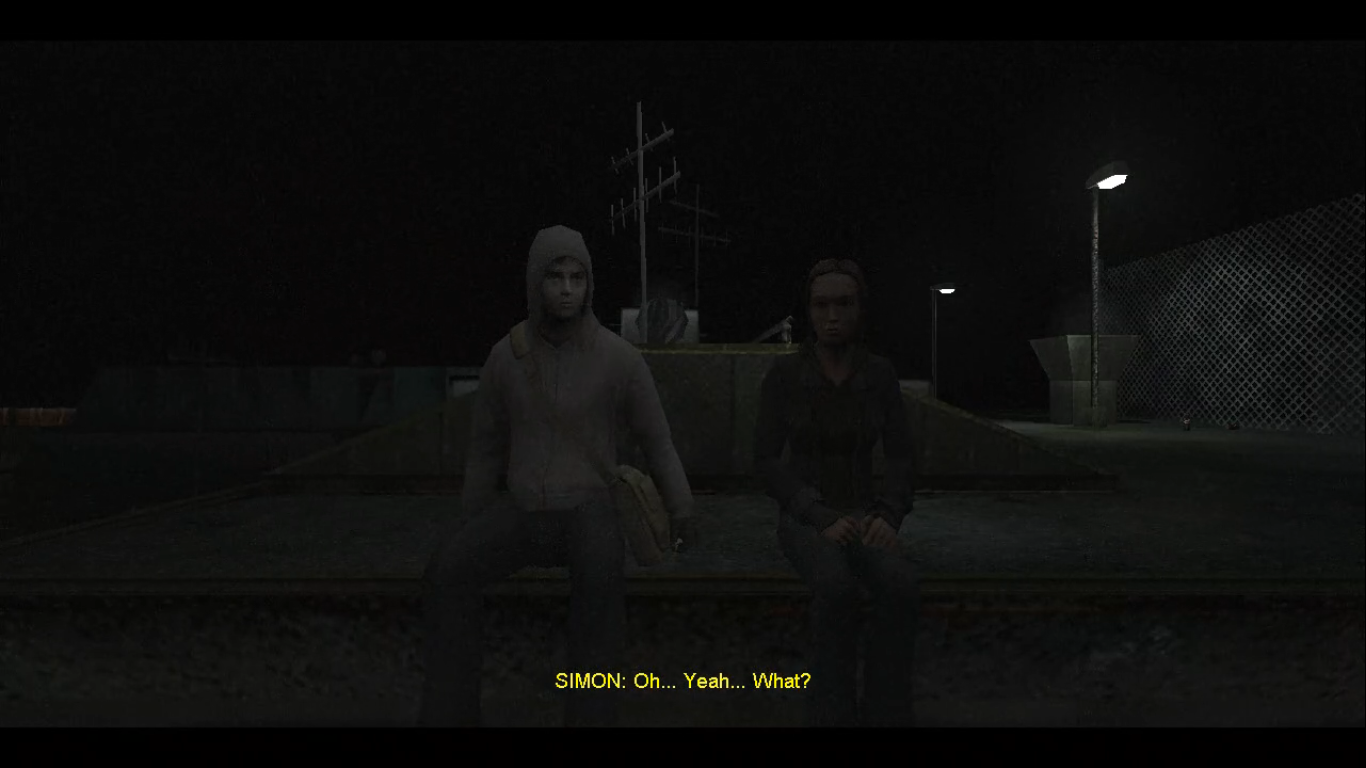

Character Loss and Loneliness

The third chapter of Cry of Fear brought me to Waspet Gardens, looking for a keycard. As I reached this location, I received a phone call from a stranger. I had difficulties hearing them, but I understood that they wanted to meet me on the rooftop of a nearby building. Upon reaching the rooftop, I realized that the caller was Sophie, one of Simon’s close friends. Meeting her had a profound impact on me. Sophie was the first character in the game with whom I could have an honest conversation and express my feelings. I had met Doctor Purnell but saw him as an antagonist—he had beheaded someone in front of my eyes, after all, and his gas mask gave him a rather inhuman appearance. I had also discovered a gruesome room filled with photos taken by a child predator, had found a corpse in a bathtub full of blood, and had witnessed a grisly murder in a snuff-like film. Needless to say, the encounters I had had with other humans to that point in the game had been rather disturbing. The conversation with Sophie provided me with the first peaceful moment of the game after roughly five hours of terror. Simon and Sophie sat down together on the edge of the rooftop, their legs dangling in the air, and talked about school life (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Talking with Sophie on a rooftop. Screenshot by the author.

While the conversation was at times a little clichéd, I found it overall touching and deeply humane in a world full of monsters, violence, and gore. The soundtrack changed from eerie music to calm and melancholic. The sequence alternated between shots of Simon and Sophie talking together, the city at night, and the stars shining in the sky, giving the scene an overall soothing atmosphere. It was comforting to be able to interact with someone else in a genuine way, and for the first time in the game, I did not feel alone. But the scene suddenly turned tragic:

SIMON: Yeah really… Was it you who tried to phone me by the way?

SOPHIE: Yeah… I wanted to talk to you. To get away from it all.

SIMON: Oh, but what, out here?

SOPHIE (standing): No… Away from everything, away from all this.

SIMON: What? What do you mean?

SOPHIE: You know full well what I mean.

SIMON: Wait a sec… You mean all…

Sophie jumps off the rooftop and kills herself.

The fact that the scene abruptly ended with Sophie jumping to her death instantly transformed a comforting moment into a traumatic one, bringing the theme of suicide to the centre of the game.5 I could not believe what had just happened. It was so sudden. I was sad and shocked. I was screaming in my head with Simon: “NO! No no no!” I felt as if something had just slipped from my hand, as if I had not been fast enough to grab Sophie’s arm and prevent her from jumping. Although I had only gotten to know Sophie for a few minutes, I was already getting attached to her and feeling less lonely thanks to her. Sophie’s suicide evoked for me the absurdity of existence, the feeling that everything was meaningless, pointless. “Why did she?” as Simon told himself. “This… this isn’t making any sense!” Sophie had not been suddenly killed by a monster during a peaceful moment with Simon—a common horror trope—but had chosen to end her life. I kept wondering why I was surrounded by death and what was the point to keep existing as Simon, to keep suffering.

Sophie’s death strongly resonated and stayed with me for the rest of the game. Each later allusion to suicide—whether through monsters who kill themselves or through references to depression and self-harm—would always bring to mind both Simon’s suicidal thoughts and Sophie’s tragic end. Meeting Sophie had brought solace to my dark journey, but following her death, I felt that “the world . . . ha[d] become poor and empty,” to use Freud’s (1917/1957, p. 246) description of mourning. The absence of other humans or meaningful relationships in the game was not only affecting Simon but was affecting me as well. Cry of Fear had successfully put me in the same position as Simon—not knowing more than him where I was and what was going on—reducing narrative and affective mediation and making the experience of loss and loneliness more hurtful. I was alone again and slowly realizing that it was going to be like this until the end of the game.

Murder, Care, and Empathy

My gaming experience ended tragically. I witnessed Simon shooting himself and then found myself in a nightmare sequence. As I took back control of my character, the chaotic audio—a mix of white noise, heavy breathing, screams, and reverberations—immediately shook me. I felt claustrophobic and found it hard to breathe, as if my breathing were unconsciously following the ragged breath I was hearing. I walked past hanged corpses, ran through a series of twisted corridors, and finally found myself in a room filled with books floating in the air, a reference to Simon’s book therapy. Several pieces of paper were scattered over the floor; others were circling around the books, as if caught in a tornado. I started jumping from one book to another, trying to reach the top of the room, only to realize to my great despair that the word “suicide” was written in blood several times inside each book. I suddenly remembered the title of the game chapter: “My Life Ends Here.” Each of my jumps was bringing Simon closer to his death, higher and higher, as a soul leaving his body. I knew what was going to happen and it now seemed inevitable: death was the only option for Simon.

I arrived in a new room, walked through a narrow corridor, and took an elevator. I naively thought that I was symbolically going to Heaven, but the elevator went down. I realized that I was probably going to Hell, and the next segment convinced me that it was the case. The game ended with a boss fight against Sick Simon (see Figure 7). At the end of the fight, my character ran toward him, beat him, and pushed him off his wheelchair. After witnessing this disturbing moment, I had to strangle Sick Simon by pressing the left button of the mouse, clearly becoming complicit in his death. For the first time in the game, a horrifying death scene was happening not because of a character over which I had no control, but because of my own actions. While several times in the game I had felt that the onscreen violence was transmitted to me offscreen (Ndalianis, 2012, p. 5), I felt for the first time that the offscreen violence—the violence I was responsible for—was transmitted onscreen. I was not pressing a button to shoot or hit an ugly monster out of self-defence. I was closing my hand around the mouse like if it were someone’s neck, firmly pressing the left button, and contracting my entire arm to strangle a defenseless Simon. My movement offscreen was violent and close enough to what I could see onscreen to feel real. Simon was choking, gasping for air, and slowly dying. I stopped pressing the mouse for a moment, as if to make sure I was the one responsible for this murder, unconsciously hoping that it was a cutscene.

Figure 7: Boss fight against Sick Simon. Screenshot by the author.

After having gone with Simon through all the horror that was Cry of Fear, I was made the last perpetrator in this tragic chain of events and now had to carry the burden of ending his life. Simon had been made a strong anchor for empathy: I had accompanied him throughout his traumatic journey—experiencing trauma myself in the process—had sought to better understand his life, and wanted the best for him. As Sick Simon’s health bar was progressively depleting, that of my character was depleting as well, until both emptied at the same time. I had killed Sick Simon, who was presented to me as an enemy, but I firmly knew that Sick Simon was simply Simon, my self and the character I had been taking care of for roughly fifteen hours. While I regretted earlier that the game took away my agency and did not allow me to stop Sophie from jumping to her death, I was now regretting that the game gave me agency, and in so doing, made me complicit in Simon’s murder. Cry of Fear had successfully led me to be emotionally invested in Simon’s fate and had convinced me that he deserved care and happiness, making the act of killing him to finish the game feel deeply wrong.

Conclusion

Cry of Fear led me to experience videoludic trauma because of its narrative, visuals, sound and music, combat system, and the feelings of loneliness and complicity it evoked in me. In my analysis, I have highlighted different aspects of the game that strongly resonated with me and made my gaming experience go from positive discomfort to videoludic trauma. While I have analyzed some of these elements separately for the sake of clarity, it is the combination of all of them within the same game that produces a specific gaming experience and creates a space that is horrifying, overwhelming, and that ultimately breaks with horror flow and wounds the player. Playing Cry of Fear was for me an unpleasant experience that put into question my assumptions about the horror genre: I did not know before playing this game that it was possible to experience fear and horror so strongly. As Emmanuel Siety (2006) observes, watching a horror film—or playing a horror game, I would add—is like playing a game with the director,

a game always a little bit dangerous because we are never sure that the film will not cross the lines of what we can endure. Without doubt, this is the first thing we are afraid of: to let ourselves be surprised by the image we did not want to see, the shocking image and the one that is really doing us violence. (pp. 9–10, as cited in Perron, 2018, p. 69)

This quote describes well my experience with Cry of Fear: the shocking images of violence, suicide, and depression did me violence. The onscreen violence continued offscreen, across my body, to paraphrase Ndalianis (2012, p. 5). Thinking back about my experience playing Clock Tower, Resident Evil Zero (Capcom Production Studio 3, 2002), or The Evil Within (Tango Gameworks, 2014)—three games I have finished—generates feelings of excitement, nostalgia, and pride, but I hardly experience any of these feelings when I think of Cry of Fear. In fact, revisiting my memories of this game to write this paper was rather challenging. Watching back over my playthrough, looking at pictures of the game, and reading about it made me feel anxious, nauseous, and even depressed. I can hardly recall any good memories I have playing Cry of Fear, and I do not think I will ever play this game again. For me as a player, there will be a “before” and an “after” Cry of Fear. This is what pushes me to argue that I experienced a form of trauma.

Trauma is a sensitive topic that must be handled with care, but it is nonetheless a topic that deserves academic attention considering its ubiquity in video games and other media. Horror video games in particular propose a fascinating case study to investigate trauma due to the range of emotions they lead the player to experience, “from visceral feelings of disgust to ecstasy, loathing to sympathy, suspense and fear to relief” (Ekman & Lankoski, 2009, p. 181). While certain types of games are more likely to generate videoludic trauma than others, it is crucial to keep in mind that games affect us differently. The idea that Cry of Fear generates videoludic trauma is based on my own gaming experience, and I do not claim that my analysis is applicable to everyone’s experience; however, I believe that the analytical tools provided in this paper can be used to better understand experiences with other games that belong to the horror genre or that engage with trauma. As scholars, it is crucial that we respond to trauma narratives “in a way that does not lose their impact, that does not reduce them to clichés or turn them all into versions of the same story” (Caruth, 1995, p. vii). Deeply engaging with these narratives by bringing in our own experiences with them is a strong way to do so.In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the evolution of games that are considered trauma-like by players and see to what extent these games are the product of specific cultural or historical moments. Will games like Spec Ops or Cry of Fear still be described as such in a decade or two? Will post-apocalyptic games filled with zombies and infected be more effective now that we have faced a global pandemic? Considering the subjective nature of videoludic trauma, it will become easier to reflect on such questions as more researchers, critics, players, mental health professionals, and trauma survivors engage with trauma theory and provide personal accounts of their gaming experiences.

Endnotes

1. Similarly, a game segment that is a priori disturbing might end up being less shocking than it initially was (Mortensen & Jørgensen, 2020, p. 139).

2. I am referring here to games like Clock Tower (Human Entertainment, 1995), Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996), Silent Hill (Team Silent, 1999), Fatal Frame (Tecmo, 2001), and Resident Evil Zero (Capcom Production Studio 3, 2002).

3. “SJÄLVMORD / MÖRDA DIG SJÄLV SOM FAN.”

4. Ndalianis (2012) originally made this claim about films from the “New Horror Cinema.” I am building on her work and applying it to video games.

5. The player learns at the end of the game that Sophie did not commit suicide in the “real” world. I am interpreting the scene here based on what Sophie’s suicide meant for me as a player making sense of the game at that particular moment.

Author Biography

Samuel Poirier-Poulin is a PhD candidate in film studies at the Université de Montréal, Canada, specializing in the study of video games and gaming cultures. His doctoral research investigates trauma in horror video games and draws on affect theory and phenomenology of media. His other research interests include romance and queer desires in the visual novel, autoethnography, and multilingual scholarship. Samuel’s work has appeared in Synoptique: An Online Journal of Film and Moving Image Studies, Loading: The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association, and in the anthology Video Games and Comedy. Since 2022, Samuel is the Editor-in-Chief of the game studies journal Press Start. You can find out more about his work on his website: www.spoirierpoulin.com

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Frans Mäyrä, Jaakko Stenros, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. I am also grateful to Syksy Johanna Siitari and Carl Therrien for their encouragement, and to the Fonds de recherches du Québec – Société et culture for their financial support. Lastly, I would like to thank the editorial board of the Journal of Games Criticism for its time and dedication, and for allowing its authors to publish longer research articles. It is increasingly difficult to find peer-reviewed game studies journals that allow the submission of longer manuscripts, and this is detrimental to the research we produce. Too often, it forces us to limit how extensively we engage with previous literature and to describe our methodology too briefly, and it makes research that draws on close reading and autoethnographic methods harder to produce. I hope that for the betterment of research, other journals will see the Journal of Games Criticism as an example to follow.

References

Andermahr, S. (2013). “Compulsively readable and deeply moving”: Women’s middlebrow trauma fiction. In S. Andermahr & S. Pellicer-Ortín (Eds.), Trauma narratives and herstory (pp. 13–29). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ash, J. (2013). Technologies of captivation: Videogames and the attunement of affect. Body & Society, 19(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X11411737

Ataria, Y. (2015). Sense of ownership and sense of agency during trauma. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 14(1), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-013-9334-y

Austin, H. J., & Cooper, L. R. (2021). Feeling the narrative control(ler): Casual art games as trauma therapy. Replay. The Polish Journal of Game Studies, 8(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.18778/2391-8551.08.07

Bal, M. (2002). Travelling concepts in the humanities: A rough guide. University of Toronto Press.

Balaev, M. (2018). Trauma studies. In D. H. Richter (Ed.), A companion to literary theory (pp. 360–371). Wiley Blackwell.

Benjet, C., Lépine, J.-P., Piazza, M., Shahly, V., Shalev, A., & Stein, D. J. (2018). Cross-national prevalence, distributions, and clusters of trauma exposure. In E. J. Bromet, E. G. Karam, K. C. Koenen, & D. J. Stein (Eds.), Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: Global perspectives from the WHO World Mental Health surveys (pp. 43–71). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107445130.004

Bjørkelo, K. A. (2018). “It feels real to me”: Transgressive realism in This war of mine. In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Eds.), Transgression in games and play (pp. 169–185). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11550.003.0015

Bjørkelo, K. A., & Jørgensen, K. (2018). The asylum seekers larp: The positive discomfort of transgressive realism. Proceedings of Nordic DiGRA 2018. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DiGRA_Nordic_2018_paper_18.pdf

Bowman, S. L. (2013, April 18). Bleed: How emotions affect role-playing experiences [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AtjeFU4mxw4

Brave Heart, M. Y. H. (2000). Wakiksuyapi: Carrying the historical trauma of the Lakota. Tulane Studies in Social Welfare, 21(22), 245–266.

Brown, L. S. (1991). Not outside the range: One feminist perspective on psychic trauma. American Imago, 48(1), 119–133.

Bumbalough, M., & Henze, A. (2016). Infinite ammo: Exploring issues of post-traumatic stress disorder in popular video games. In S. Y. Tettegah & W. D. Huang (Eds.), Emotions, technology, and digital games (pp. 15–34). Academic Press.

Capcom. (1996). Resident evil. PlayStation: Capcom.

Capcom Production Studio 3. (2002). Resident evil zero. GameCube: Capcom.

Caruth, C. (1995). Introduction. In C. Caruth (Ed.), Trauma: Explorations in memory (pp. 151–157). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Caruth, C. (1996). Unclaimed experience: Trauma, narrative and history. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. HarperCollins e-books. (Original work published 1990)

Danilovic, S. (2018). Game design therapoetics: Authopathographical game authorship as self-care, self-understanding, and therapy [Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto]. TSpace Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/1807/89836

Doctor, R. M., & Shiromoto, F. N. (2010). The encyclopedia of trauma and traumatic stress disorders. Facts on File.

Ekman, I., & Lankoski, P. (2009). Hair-raising entertainment: Emotions, sound, and structure in Silent hill 2 and Fatal frame. In B. Perron (Ed.), Horror video games: Essays on the fusion of fear and play (pp. 181–199). McFarland.

Elm, M., Kabalek, K., & Köhne, J. B. (Eds.). (2014). The horrors of trauma in cinema: Violence void visualization. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Farrell, K. (1998). Post-traumatic culture: Injury and interpretation in the nineties. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Freud, S. (1957). Mourning and melancholia. In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud: Vol. 14 (1914–1916): On the history of the psycho-analytic movement, Papers on metapsychology and Other works (pp. 243–258; J. Stratchey, Trans.). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1917)

Freud, S. (1961). Beyond the pleasure principle (J. Stratchey, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 1920)

Gibbs, A. (2014). Contemporary American trauma narratives. Edinburgh University Press.

Gualeni, S., & Vella, D. (2020). Virtual existentialism: Meaning and subjectivity in virtual worlds. Palgrave Macmillan.

Harrer, S. (2018). Games and bereavement: How video games represent attachment, loss, and grief. transcript Verlag.

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—From domestic abuse to political terror. BasicBooks. (Original work published 1992)

Hopeametsä, H. (2008). 24 hours in a bomb shelter: Player, character and immersion in Ground zero. In M. Montola & J. Stenros. (Eds.), Playground worlds: Creating and evaluating experiences of role-playing games (pp. 187–198). Ropecon ry.

Human Entertainment. (1995). Clock tower. Super Nintendo Entertainment System: Human Entertainment.

Infinity Ward. (2007). Call of duty 4: Modern warfare. PlayStation 3: Activision.

Jagoda, P. (2013). Fabulously procedural: Braid, historical processing, and the videogame sensorium. American Literature, 85(4), 745–779. https://doi.org/10.1215/00029831-2367346

Jennings, S. C. (2018). The horrors of transcendent knowledge: A feminist-epistemological approach to video games. In K. L. Gray & D. J. Leonard (Eds.), Woke gaming: Digital challenges to oppression and social injustice (pp. 155–171). University of Washington Press.

Jørgensen, K. (2016). The positive discomfort of Spec ops: The line. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 16(2). https://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/jorgensenkristine

Keogh, B. (2018). A play of bodies: How we perceive videogames. MIT Press.

Kłosiński, M. (2022). How to interpret digital games? A hermeneutic guide in ten points, with references and bibliography. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 22(2). http://gamestudies.org/2202/articles/gap_klosinski

Kromand, D. (2008). Sound and the diegesis in survival-horror games. Proceedings of Audio Mostly Conference—A Conference on Interaction With Sound, 16–19.

Krzywinska, T. (2002). Hands-on horror. Spectator, 22(2), 12–23.

Kuznetsov, E. (2017). Trauma in games: Narrativizing denied agency, ludonarrative dissonance and empathy play [Master’s thesis, University of Alberta]. Education & Research Archive. https://doi.org/10.7939/R30Z7196H

LaCapra, D. (2001). Writing history, writing trauma. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lowenstein, A. (2005). Shocking representation: Historical trauma, national cinema, and the modern horror film. Columbia University Press.

Luckhurst, R. (2008). The trauma question. Routledge.

Montola, M. (2011). The painful art of extreme role-playing. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 3(3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.3.3.219_1

Moody, A. T., & Lewis, J. A. (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and traumatic stress symptoms among Black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319828288

Mortensen, T. E., & Jørgensen, K. (2020). The paradox of transgression in games. Routledge.

Mukherjee, S., & Pitchford, J. (2010). “Shall we kill the pixel soldier?”: Perceptions of trauma and morality in combat video games. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 2(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.2.1.39_1

Ndalianis, A. (2012). The horror sensorium: Media and the senses. McFarland.

Newman, J. (2002). The myth of the ergodic videogame: Some thoughts on player-character relationships in videogames. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 2(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/newman/

Perron, B. (2004, September 14–16). Sign of a threat: The effects of warning systems in survival horror games [Conference presentation]. COSIGN 2004, the 4th International Conference on Computational Semiotics, Split, Croatia. https://ludicine.ca/sites/ludicine.ca/files/Perron_Cosign_2004.pdf

Perron, B. (2005, October 14–15). Coming to play at frightening yourself: Welcome to the world of horror games [Conference presentation]. Aesthetics of Play: A Conference on Computer Game Aesthetics, Bergen, Norway. https://ludicine.ca/sites/ludicine.ca/files/Perron%20-%20Bergen%20-%202005.pdf

Perron, B. (2018). The world of scary video games: A study in videoludic horror. Bloomsbury Academic.

Pinedo, I. C. (1997). Recreational terror: Women and the pleasures of horror film viewing. State University of New York Press.

Plantinga, C. (2009). Moving viewers: American film and the spectator’s experience. University of California Press.

Playdead. (2010). Limbo. PC: Playdead.

Pope, L., & 3909 LLC. (2013). Papers, please. PC: Lucas Pope & 3909 LLC.

Quantic Dream. (2010). Heavy rain. PlayStation 3: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Quantic Dream. (2013). Beyond: Two souls. PlayStation 3: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Southern Illinois University Press.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1986). The aesthetic transaction. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 20(4), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/3332615

Rothe, A. (2011). Popular trauma culture: Selling the pain of others in the mass media. Rutgers University Press.

Rusch, D. C. (2009). Staring into the abyss—A close reading of Silent hill 2. In D. Davidson (Ed.), Well played 1.0: Video games, value, and meaning (pp. 235-253). ETC Press.

Sapach, S. (2020). Tagging my tears and fears: Text-mining the autoethnography. Digital Studies / Le champ numérique, 10(1). http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.328

Schwab, G. (2010). Haunting legacies: Violent histories and transgenerational trauma. Columbia University Press.

Sicart, M. (2011). Against procedurality. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 11(3). http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap

Smethurst, T. (2015). Playing with trauma in video games: Interreactivity, empathy, perpetration [Doctoral dissertation, Universiteit Ghent]. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-5930001

Solomon, R. C. (2004). In defense of sentimentality. Oxford University Press.

Tango Gameworks. (2014). The evil within. PlayStation 3: Bethesda Softworks.

Team Psykskallar. (2013). Cry of fear. PC: Team Psykskallar.

Team Silent. (1999). Silent hill. PlayStation: Konami.

Tecmo. (2001). Fatal frame. PlayStation 2: Wanadoo Edition.

Tronstad, R. (2018). Destruction, abjection, and desire: Aesthetics of transgression in two adaptations of “Little red riding hood.” In K. Jørgensen & F. Karlsen (Eds.), Transgression in games and play (pp. 207–218). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11550.003.0018

United States Army. (2002). America’s army. PC: United States Army.

Valve. (1998). Half-life. PC: Sierra Studios.

Van der Kolk, B. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/bvdkolk

Van Elferen, I. (2015). Sonic descents: Musical dark play in survival and psychological horror. In T. E. Mortensen, J. Linderoth, & A. M. L. Brown (Eds.), The dark side of game play: Controversial issues in playful environments (pp. 226–241). Routledge.

Whalen, Z. (2004). Play along—An approach to videogame music. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 4(1). http://www.gamestudies.org/0401/whalen/

Yager Development. (2012). Spec ops: The line. PlayStation 3: 2K Games.