by Hongwei Zhou

Published December 2024

Download full pdf of article here.

Abstract

There are many divergent articulations and definitions of agency in game studies, characterized by differing disciplinary interests and motivations. This article seeks to find productive differences among a selection of scholarship through a post-humanist and anti-essentialist lens. Through this lens, I define agency as the power and accountabilities implicated in a causal structure, consisting of entities and their relations. This article argues for a productive interpretation of the various articulations of video game agency. Each articulation designates a specific causal structure for analysis and intervention, which I term a modality of agency. Through the philosophies of Barad and Deleuze, I propose a framework to see these causal structures as contingent, fluid and unstable. The determination of entities and their structures designate a fixing of relations and a commitment to material-discursive practices that should not be taken for granted. As a result, agency is also capable of shifting, morphing, and breaking down. Its determination already involves a global situation, where various modalities can dissolve or emerge based on instances of play. I propose the infrastructure metaphor to understand video game’s relationship to agency; video games direct the determination of agency rather than dictate its results. This contrasts with many ludic-centric analyses of agency in game studies, where agency is grounded within the choices and rules provided in the game. I study the game Rhythm Doctor to demonstrate how this framework can make sense of game genres whose richness is not typically associated with its rules, unearthing the various modalities of agency already involved in the one-button rhythm game.

Keywords: agency, post-humanism, post-structuralism, anti-essentialism, Karen Barad, Gilles Deleuze, Rhythm Doctor

Introduction

Agency is a tricky concept that has been defined and re-defined across different scholarly fields (Eichner, 2014). It sees wide adoption in colloquial discussions around video games due to the medium’s interactive nature. But insofar as it is colloquial, it is also hard to hold stable. One of the earliest and influential definitions in game studies was articulated by Murray (1997) as “the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices” (p. 324). Other scholars have elaborated on this definition since, especially to inform design practices (Mateas, 2001; Wardrip-Fruin et al., 2009). This conception of agency has its roots within the interactive nature of the medium, so is often directed towards studies of game mechanics and player experiences (Bódi, 2023; Jenning, 2019). Jennings (2019) comments that “much of the field of game studies functions in response to Murray’s [definition of agency]”, either extending, complicating or breaking away from this conception (p. 85).

The post-humanist turn (Braidotti, 2013) informs many game scholars’ challenges and complications of this foundational definition. Oriented around challenging humanist and anthropocentrist perspectives, post-humanism in game studies has been fruitful for tackling many issues such as video games’ relationship with techno-culture, environmental concerns and planetary ecologies. The aim of post-humanism can largely be framed as challenging the ontological divides between the human/nonhuman, organic/inorganic, culture/nature that often surface in the humanities (Daigle & Hayler, 2023). The position taken is often described as “flat ontology” that does not take human subjectivity and agency as given and primary (Wilde, 2023). Barad’s (2007) agential realist philosophy, often cited in post-humanist scholarship, seeks to challenge the individualist metaphysics “that take ‘things’ as ontologically basic entities” (p. 138). To Barad, agency is not a property attributed to a ‘thing’, but the constant ‘doing’ and ‘being’ in the entanglement of matters (p. 178). This view is echoed by many post-humanist arguments in game studies that suggest non-human beings such as inorganic objects, materials, animals, plants, and even non-player characters (NPCs), exert agency upon play and shape the player experience (Giddings, 2007; Girina & Jung, 2019; Imbierowicz, 2023; Ruffino, 2020; Wilde, 2023).

Aligning with other post-humanist scholarship in game studies (Fizek, 2022; Hao, 2023; Janik, 2018; McKeown, 2019; Petris de & Falk, 2017; Wilde & Evans, 2019), this article centers on exploring the questions of entities, or ‘things’, when they are no longer taken as ontologically primary. Entities in the forms of names and concepts are nevertheless descriptive and functional to obtain knowledge and to inform decisions and actions. Through conceptualizing entities and their relations, causal powers and accountabilities are assigned to entities as an inevitable process of trying to make sense of the world. This assignment of causal power underlies the various articulations of agency in game studies.

To substantiate this point, I conduct a literature review of existing definitions of agencies in game studies in the first section of this article. I consider how different causal powers and accountabilities are assigned to different entities (the player, the social, the system etc.) through their relations as articulated in different definitions of agency. Instead of being in conflict, I argue that different definitions designate different modalities of agency — play can encompass different modalities of agency that fluctuate based on circumstances from moment to moment. Thus, I argue that video games’ relation to agency is not fixed nor pre-determined, but rather contingent on the entanglement of gamic, personal and social factors.

Inspired by the philosophies of Deleuze (1968/2014) and Barad (2007), I propose the infrastructure metaphor to describe video games’ relation to agency; video games direct processes of agency’s determination rather than dictate its terms by confining them to a particular modality, such as choices fixed within the rules. This conception of video games’ relation to agency allows a wider appreciation of video games’ capacity to surface agency beyond their ludic structures, such as the player’s social agency, their agency towards their own body, and their agency to the world at large. I study the game Rhythm Doctor (7th Beat Games, 2021)to demonstrate how the infrastructural metaphor can offer a useful analytic frame that detaches agency from mere rules and mechanics to a broader view of agency that is emergent and socially situated. The player’s subjectivity, in this case, is no longer stable nor fixed upon the organic body; their agency is no longer purely directed from the organic body outwards to the world. Rather, the player’s subjectivity can shift within a field of human and nonhuman matters; and the player agency can be directed towards the game, the body itself, or the larger social and historical situation that conditions play. The infrastructural metaphor compliments the post-humanist aim through an analytical frame that sees entities such as the player as unstable and distributed, enforcing their entangled nature with the world and de-naturalizing their agency as of a humanist and anthropocentric nature.

Suggestion, Intention and Transformation

As I demonstrate in this section, existing literature constructs the entities involved in agency and play differently. To start, I want to define three domains of activities shared by each articulation. Each domain designates a category of phenomenon loosely tied together. Some examples are listed as follows:

- Suggestion: language, implications, conventions, genres

- Intention: mental models, thoughts, cognitions, pre-cognitive mechanisms

- Transformation: physical acting, playing, changing of material state

These categories are provisional in nature, and support analysis in two ways: firstly, the categories are abstracted in a way that is agnostic to objects of scholarly concerns, but nevertheless ties together loosely related inquiries; for example, suggestion would include both the effects of language use and socialization that shifts the meaning of words or signifiers. Secondly, the interaction between each category can more easily illustrate, group and contrast different definitions of agency; in Baradian terms, they show how each domain “comes to matter” in each definition (Barad, 2007, p. 137). Through different ways of relating the domains, the entities such as “player”, “game” and “culture” are attributed different causal powers and accountabilities in the definitions, and thus different modalities of agency.

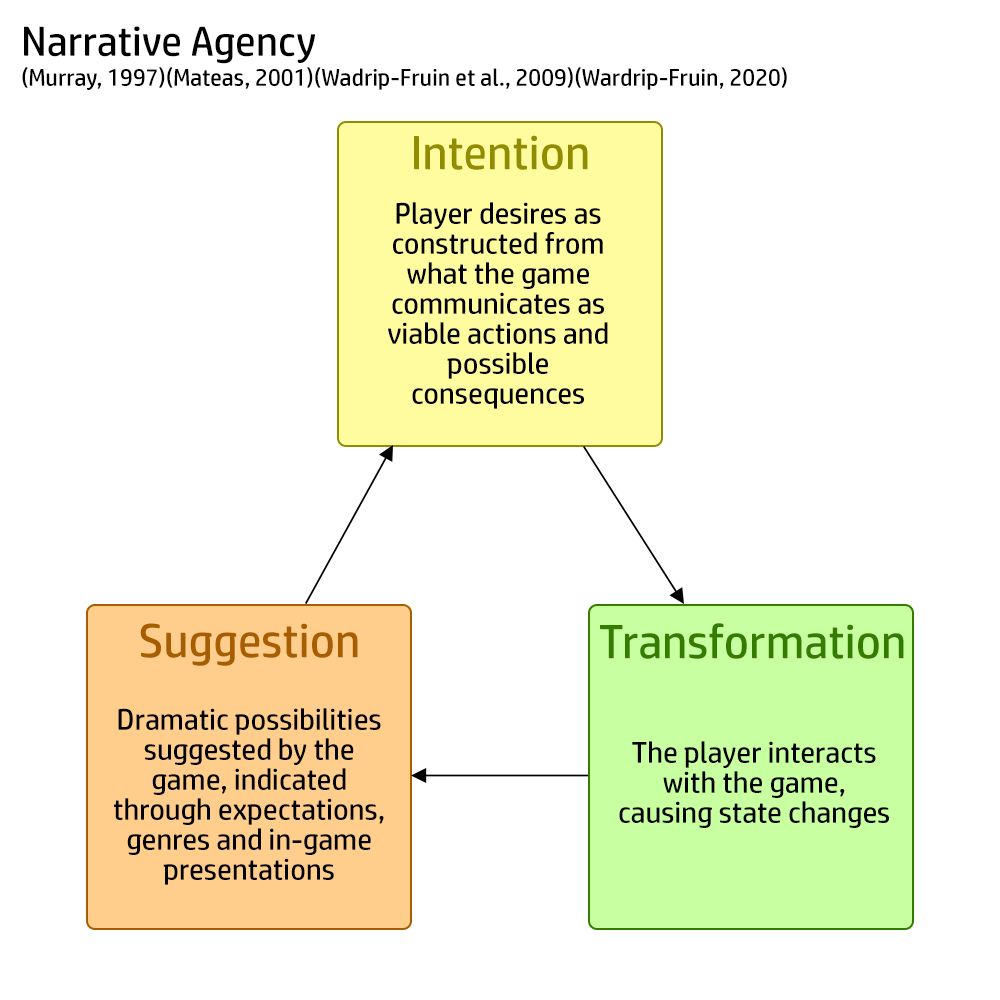

Narrative Agency

The first group of definitions stems from Murray’s (1997) articulation of agency as “the satisfying power to take meaningful action” (p. 324) and was further developed by Mateas and Wardrip-Fruin et al. (Mateas, 2001; Wardrip-Fruin et al., 2009; Wardrip-Fruin, 2020). Figure 1 illustrates a general summary of this definition.

Narrative agency considers player intention as enabled by interaction possibilities based on presentations in the game, as represented by the arrow from suggestion to intention. These presentations can be an NPC or quest suggesting doing something or going somewhere, or expectations such as first-person shooters suggesting the player can use guns. The player then acts out their understanding of the game from intention to transformation. From transformation to suggestion, the game provides feedback to the player, and changes the field of suggestion. This loop describes the player learning the “grammar” of the game and forming an understanding of what their capacity to act is within the game. Agency here is realized through the intention in harmony with the field of suggestion and transformation, or in Mateas’ words, a balance between formal cause/affordance and material cause/affordance – what the game suggests one can do and what one can actually do as afforded by the software (2001, p. 3). Wardrip-Fruin et al. further argue that agency is “a phenomenon involving game and the player” (2009, p. 1), and not purely grounded within the player (agency can be illusive) nor structural properties of the game (agency is absent of the player).

In this group of definitions, both suggestion and transformation attach themselves closely to what is contained within the artifact. It is no surprise, then, that this definition is typically associated with design theory (Girina & Jung, 2019). Mateas’ (2001) original motivation was to use the definition to understand interactive drama. Wardrip-Fruin later developed the concept of operational logic to envision ludic logic as both functional on the software level and communicative on the suggestive level (2020). By grounding suggestion and transformation to the artifact, designers can imagine their relation to player agency as something that they can refine through craftsmanship. Whether or not intention achieves a balance between suggestion and transformation is left to the designer to observe and judge, but it is interesting to consider the role of intention in this dynamic/distribution of parts. The “player” entity here is specifically accountable for achieving the harmony between suggestion and transformation (learning the game). The physical acting within transformation only focuses on the player acting on the game artifact, and the way the artifact acts back is through presentations and feedback in the form of suggestion. The focus centers on the interactive loop between the player and the game, thus the entities, their relations, and the agency implied focus on the particularities within the loop.

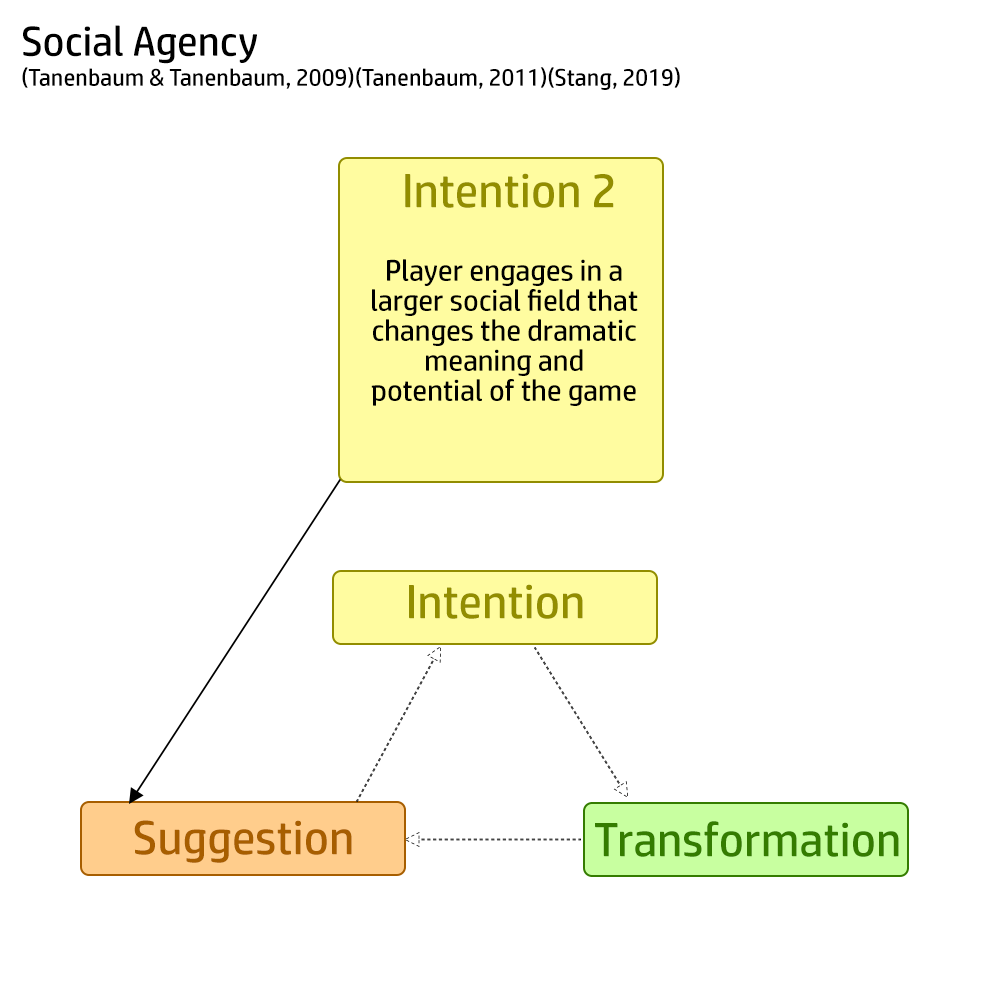

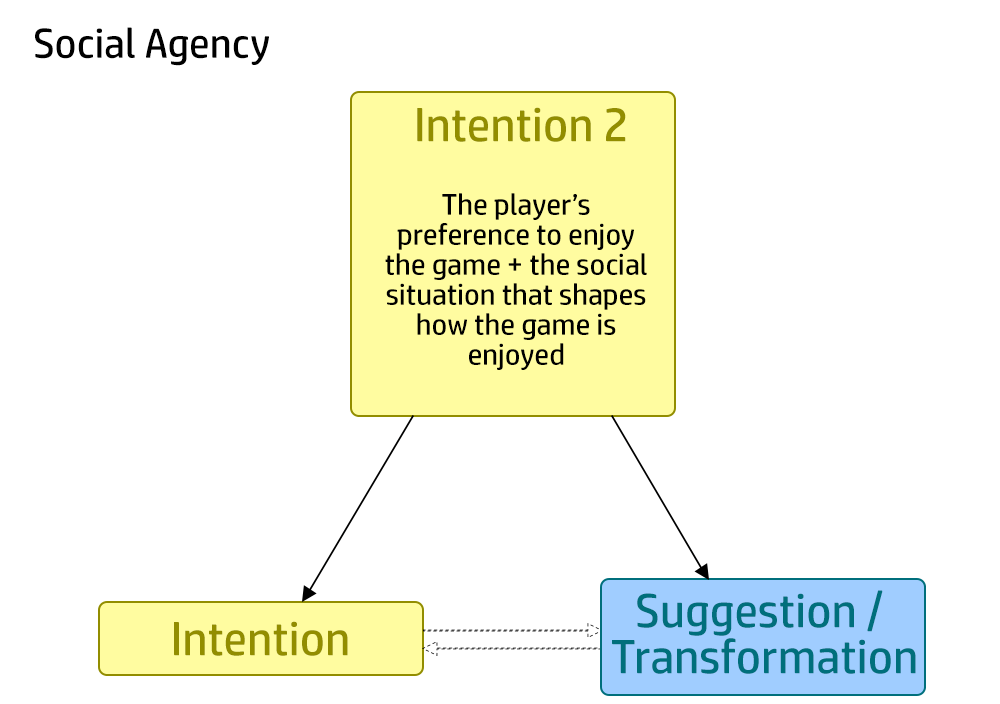

Social Agency

The second group of definitions of agency becomes relevant when we consider that suggestion is much larger than what is being evoked in the game and about the game. Even in the previous definitions, the larger social field that makes suggestion possible lies latent, in the background without a proper shape or form. The second group of definitions expands the social as part of the player’s agency (see Figure 2).

The intention here is separate from the intention discussed in relation to narrative agency because it is constructed based on a completely different dynamic. This intention is accountable for, or possesses the non-trivial capacity of, shifting suggestion within the game. Drawing from theories in theatre and speech act theory, Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum (2009) reframe the player agency as participation and commitment to meaning. Similarly to actors transforming themselves into their roles, this social agency recognizes the active effort involved in embodying the role of the player and the character. Tenanbaum (2011) also draws out the aesthetic dimension within this commitment to meaning, arguing that “[t]his sensation of performing a role is an unusual blend of freedom and constraint; it is a type of bounded agency that results in a unique narrative pleasure” (p. 55) On the other hand, Stang (2019) articulates this social agency in a more negative way, in terms of the player subject breaking away from suggestion within the game. Stang uses the unfortunately named “true player agency” to describe “the players’ interpretations of the game text, in their engagement with fan communities, and in the exchanges that occur between fans and developers” (2019). Stang is interested in the player’s ability to engage with communities to resist the passive player subject as shaped by the designer and the game, to establish a social power structure where the subject realizes their capacity.

This social agency is not new to media studies. Fiske, writing on television, has criticized how the “textual subject” casts the viewer as powerless and inactive, while a social subject “is more influential in the construction of meanings than the textually produced subjectivity which exists only at the moment of reading” (1987/2010, p. 62). Fiske details many social factors and scenarios that dramatically influence how television is consumed: children only paying attention when dramatic scenes take place, queer and marginalized groups producing readings in conversation with their experiences, people engaged in oral culture watching with an interest to converse with friends, and so on. One can easily imagine how these cases can be applied to gaming. Indeed, Wardrip-Fruin et al.’s description of the player subject has a particular dedication to the text, where external assumptions are to be selected in order to serve the harmonization with the game: “To play successfully they must transition from their initial assumptions about this domain […] to an understanding, often largely implicit, of how it is supported by the software model” (2009). But a social subject realizes that social externality is an important factor that shapes perceptions of the game, even if that externality is loosely or wholly unrelated to the game itself.

This conceptualization of social agency is consistent with empirical findings and ethnographic studies of game culture. Through their interviews with players, Carstensdottir et al. observe that “players do not necessarily have a fixed idea of what high or low agency entails and evaluate this in context with the game itself and their experience and knowledge of games that they consider to be similar or of the same genre” (2021, p. 11), thus firmly grounding the player’s conception of their agency within their social history. The interviews also show traces of gaming discourses influencing player’s conception of their agency, such as interviewees being annoyed by dialogue choices that “obviously don’t matter” in The Wolf Among Us (Telltale Games, 2014), or interviewees disagreeing whether a complex gameplay mechanics without narrative impact mean more or less agency for the player. One can see that the player’s literacy and media consumption around video games impacts what they expect from the game. The speedrunning community also demonstrates how sociality can dramatically change the formal affordance/suggestion in the game (Boluk & LeMieux, 2017, p. 43). Ruberg (2019) describes speedrunning as embodying queerness that “represents a resistance to the standard logics that dictate what one should do, where, when, and at what speed.” (p. 185) Through rejecting the normalized ways to progress through games, speedrunners also perceive the material affordance/transformation of the game differently; a walled corner might mean navigational boundaries for most, but it might mean collision box glitches that open new navigational possibilities for others. Thus, what is supported by the computational model is also already contingent on social practices and can be subverted and made indetermined by the very materiality of the game itself. While these examples demonstrate how suggestion of the game can change based on social settings, social agency realizes that the player is accountable for either committing to or rejecting these social spheres, starting from as trivial as choosing to play the game just to enjoy it, to the significant commitment of immersing oneself in a particular gaming community.

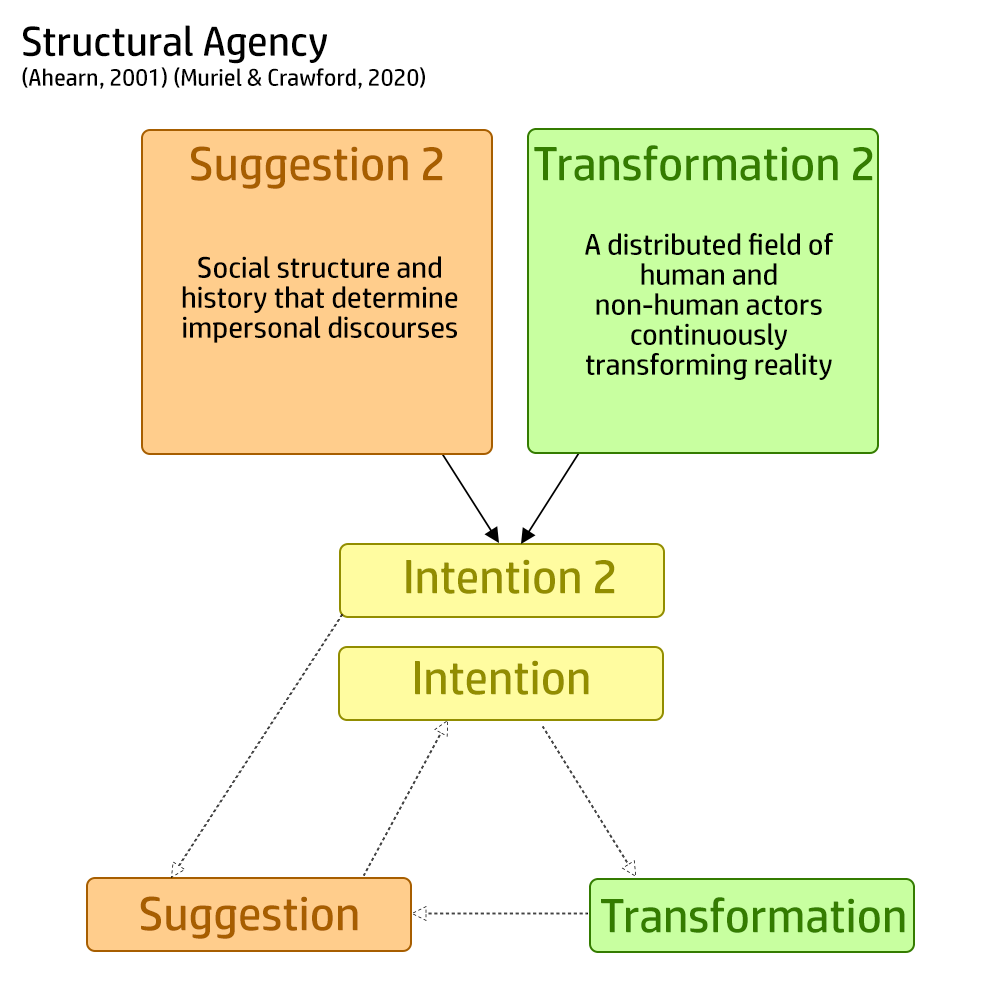

Structural Agency

The third and last group of definitions of agency reflects efforts to decenter intention, and the naïve humanist notions of freedom, autonomy and free choice it carries, as the source of a causal chain. Social agency refers to the social field merely through an individual’s commitment to it, while this final category instead foregrounds non-human and impersonal fields conditioning that very commitment (see Figure 3).

This group of definitions realizes that individual subjects exist within a distributed structure of power that influences the very possibilities of their thoughts, knowledge and capacities.Muriel & Crawford’s (2020) post-humanist articulation of agency applies Latour’s actor-network theory and defines it as “what produces differences and transformations” without intentions, represented by transformation 2 (p. 142). This definition echoes Barad’s (2007, p. 178) notion of agency as not an attribute but as ‘doing’ and ‘being’ of matters. Defining agency this way highlights how both humans and nonhumans are constantly acting on each other in the world, and explains “why video games—but also the hardware, connections, and peripherals that make the interaction possible—can be considered as actors” (Muriel & Crawford, 2020, p. 142). This view makes it difficult to define where human intention begins and ends. Indeed, Muriel & Crawford define this agency as both “distributed” and “not resid[ing] in a prototypical actor” (p. 142). Intention is thus defined as a structural property, “an attribute of dispositifs, apparatuses, institutions or … assemblages”, represented as arrow from transformation 2 to intention 2, where the apparent human intention that is capable of choosing social commitments is already conditioned by their material circumstances. Muriel & Crawford bring up Millington’s (2009) study of Nintendo’s Wii, and specifically the design features and developer blogs of Wii Fit (Nintendo EAD, 2007), as an example of the agency of game consoles. Millington (2009) argues that the Wii acts as a quasi-expert to reinforce a static image of body normativity and as a device whose position as casual entertainment furthers the personal responsibiliziation of bodily health.

Instead of material structures, impersonal fields also include discursive structure that the subject is submerged in, represented by suggestion 2. Though not in game studies, Ahearn articulates this complex relation between social structures, discursive practices and agency most thoroughly. Ahearn defines agency as “socioculturally mediated capacity to act” and discusses findings in linguistic anthropology to demonstrate how even grammatical structures regulate the perceptions of causality and agentive capabilities (2001, p. 112). Game studies scholarship that tackles discursive practices can often be understood similarly as demonstrating the agency of discursive structures, within which a player’s understanding of their own agency is conditioned. One such example would be Wright’s (2022) study of Red Dead Redemption (Rockstar Games, 2010)that explores how the developer Rockstar utilizes paratexts such as trailers and blog posts to shape the public perception of the game. Although Red Dead Redemption depicts the old West with a lens shaped by the setting’s film history, and with an emphasis on its lawlessness, whiteness, and violence, its developer Rockstar still advertised the game around the framing of an authentic historical experience that intertwines “Rockstar’s brand and labor, their provision of gameplay affordances and the fictional world for the player, with the continued maintenance of a discourse of historical authenticity” (Wright, 2022, p. 117). One can see how the agency of commitment, as articulated by Tanenbaum & Tanenbaum (2009), is complicated here, as the discourse of authenticity can influence how the player commits themselves to the old Western setting (‘it’s like you’re really there’), but it is already shaped by the web of media history, game advertisements, genre fantasies and brand expectations, thus limiting their imaginary of the Western setting from the very beginning, homogenizing the understanding of a complex period in American history.

Concluding this literature review, I want to reiterate that my aim is not to point out each articulation’s definitional differences. The definitions of agency are based on what entities/objects are involved and how they relate to each other. They highlight certain causal dynamics from one entity/object to another, thus designating certain causal potency to each object, and as a whole offer up causal structures specific to each definition. These causal structures imply a distribution of accountability and inform points of intervention. For example, a strict adherent to agency defined by Wardrip-Fruin et al. (2009) means focusing on the player’s accountability in becoming attuned to the artifact. But the agency articulated by Stang (2019) attenuates this accountability by allowing deviation from the artifact to be sustained and potentially realized socially. By offering different causal structures, I understand these definitions as different modalities of agency. Each modality may have a different potency in each instance of play, some not even consciously realized by the player, but nevertheless can be utilized to interpret and analyze a particular play experience. This is following Jenning’s (2019) pluralist approach for game agency modalities. By not taking the entities/objects involved in the causal structure for granted, the accountabilities implied in each structure are conceptualized as constructed and fluid.

Infrastructure and the Flux of Indeterminacy

Building on the surveyed literature, I argue that modalities of agency are based on the causal structures offered in each definition of agency in game studies. These causal structures consist of the entities, or the ‘things’, and their relations as articulated and constructed in each definition. In this section I propose the infrastructure metaphor as a way of understanding these structures as capable of dissolving, changing and morphing. Different modalities of agency can therefore co-exist with each other, capable of being potent and relevant depending on specific instances of play.

I am particularly inspired by the philosophy of Barad (2007) and Deleuze (1968/2014) to connect this concern to a philosophical level. Both Barad and Deleuze propose anti-essentialist thinking in that they do not take an entity itself as primary. Barad (2007) defines phenomena as the primitive unit of their ontology, or “relations without preexisting relata” (p. 139), while Deleuze (1968/2014, p. 75) proposes difference-in-itself as primary to representations/entities. I unify these conceptualizations under the term indeterminacy, as a state prior to the determination of entities and causal structures. It is worth noting that Barad (2007) defines their agency as existing on this level of indeterminacy, as the ‘doing’ and ‘being’ in the entanglement of matters (p. 178). Rather than adapting this definition, I use ‘agency’ and ‘modalities of agency’ as the accountabilities implicated in a determined causal structure to better relate to different definitions of agency surveyed in the previous section.

These two anti-essentialist frameworks offer us different ways to envision how entities can change. Barad’s (2007, p. 148) concepts particularly highlight the inseparability between determined entities and the determining apparatus. Drawing from quantum physics, where properties of a quantum object only become determined when measured by an apparatus, Barad extends this phenomenon to argue that even when we engage in discourse in general, it already involves a process of entity determination that implicates an apparatus of observation, measurement and practice, such as our sensory data, social history and material circumstances. Put simply, to become determined is to be committed to a social (material-discursive) practice. Notably, game scholars like McKeown (2019) and Hao (2023) apply this view to argue that interaction between the player and the system is not isolated, but is always entangled in the material, historical and cultural structures of the world.

I also want to extend this inseparability to scholarly works on agency. Each definition of agency offers a causal structure that informs the distribution of accountability and points of intervention. But these causal structures cannot be separated from how they are utilized: to inform design, to study game artifacts, to study the sociality of gaming, or to challenge neoliberal rationalities. This conception of agency also challenges the definitional gap between agency as experience and agency as transformation in game studies, as identified by Jennings (2019), since to be able to articulate transformation (entities changing and interacting), one already has to commit to a certain material-discursive practice that implicates one’s positionality and subjectivity.

On the other hand, Deleuze’s conception of difference shifts our attention to the determined entities themselves, in terms of how the representation/entity actually subdues the creative potential of the thing that it supposedly covers over. Deleuze (1968/2014) explains that “representation fails to capture the affirmed world of difference. [It] has only a single centre […] mediates everything, but mobilises and moves nothing” (p. 70). The stability of representation/entity, in this view, is simply an imposed idea to keep certain habits of social (material-discursive) practice stable. Two concepts are useful here to understand how entities can be kept stable: contraction and distribution. Inspired by Bergson, Deleuze (1968/2014) uses contraction to discuss how elements are repeated together: A A A AB AB AB… (p. 95). This fixes the particles into relations, which imposes limits on the elementary particles (A is constrained within AB). For example, in Wardrip-Fruin et al.’s agency, the player becomes constrained as its relation becomes fixed to the artifact. The concept of agency becomes stable in its definition through this contraction of the player and the artifact. When we consider these fixing of relations/contractions en masse, this also imposes a certain distribution over the player and artifact, where each part of the player (their psychology, sociality and materiality) is supposed to contribute to agency in a certain way. In Deleuze’s (1968/2014) words, an absolute adherence to a stable entity “lives itself as a universal rule of distribution, and therefore as universally distributed” (p. 297). Thus, Deleuze’s conception of difference as primary allows us to see that the representations/entities themselves bear the possibility of newness within their parts (elementary particles), because they in themselves bear the potential to produce differences by realizing a different distribution.

The determination of objects has always been unstable, where each part is always possible to establish dominance over the other, and the distribution underneath that object can always shift and morph. Janik (2018) describes this dynamic in play, where the “qualitative new unity” between the player and the game is fundamentally unstable, “when the player is skillful, we can say that she is in a more dominant position, but the moment the game level becomes too hard to beat, the tipping point moves towards the game object” (p. 3). We can understand the different modalities of agency from the previous sections as exhibiting different distributions, as suggestion, intention, and transformation have different causal flow from one to the other. For example, the case of speedrunning discussed in the previous section shows how the way that the software contributes to suggestion can come to matter differently based on community practices: a corner can signify blockage or new navigational potential. These shifts do not change the software itself, but the distribution that each part contributes to agency. The seeming stability of constructed entity, then, obscures an agential layer through the fixing of relations, while foregrounding object-parts can reveal that layer, pushing it towards indeterminacy, and opening up new possibilities of relating, and thus new modalities of agency.

The resulting conception is that the determination of agency is deferred to the moment a causal structure is realized and utilized. Any specific instance is not localizable, but rather already entangled within various gamic, personal and social factors. Disagreement over game design decisions, perceptions of oneself as a player, and consciousness around social issues all inform the player’s decision to assign accountabilities to different entities; even non-human ones like controllers can be blamed, sometimes quite violently, for undesired outcomes. Thus, video games become infrastructure of agency. Infra- means below the determination of entities. The infrastructure metaphor imagines video games as plugged into the existing flux of indeterminacy, shifting and directing the flows and connections that determinations of agency rely on, but is not necessarily the destination that dictates the terms of determination. This contrasts with the prevailing ludic-centric approaches to agency that focus mainly on rules, software models and choices, which only designate a particular distribution and a particular modality of agency. It also allows us to apply agential analysis to genres typically not noted for their ludic richness, as I will demonstrate in the next section.

Rhythm Doctor: A Case Study

The previous section lays out an infrastructural approach to video games’ relation to agency. In short, this approach aims towards destabilizing the boundaries of entities involved in play. Inspirations through Baradian and Deleuzian philosophies point to two opposite but deeply connected directions of investigation. Through Barad, one would look outward to reveal the external material-discursive circumstances that the determination of entities is contingent upon. Through Deleuze, one would look inward to reveal that even the parts within a given entity are not stable, with shifting distribution and partial connection with the outside. The resulting conception would be a view of agency without a static modality in each instance of play, shifting in an entangled field of matter with no a-priori division between subject/object, organic/inorganic, human/nonhuman. This section applies the infrastructural approach in a case study to demonstrate this broader and more fluid view of video games’ relation to agency.

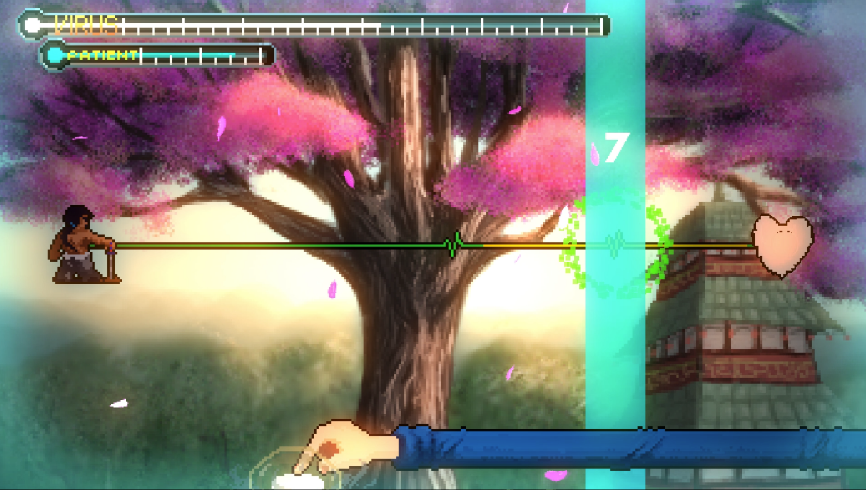

The game in focus is Rhythm Doctor, a rhythm game with only one button input, where the player has to tap the button at a certain time interval (typically at the seventh beat, as shown in Figure 4). The game is deliberately picked for the simplicity of its rules, and the necessity to look outside the artifact to appreciate the play experience. I will demonstrate how an infrastructural approach is useful to think about the richness of Rhythm Doctor’s connection to agency.

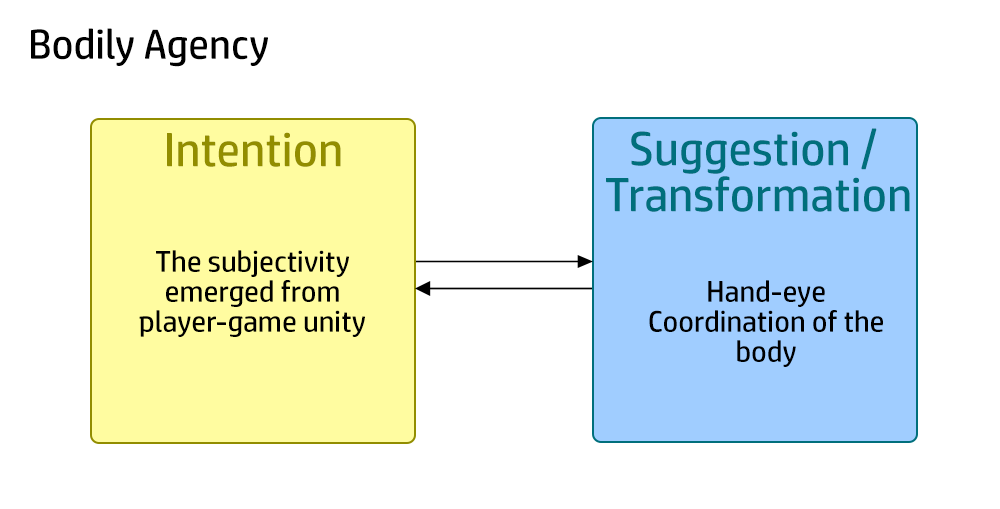

Bodily Agency: Breaking Down the Body

The modality of agency developed in this subsection destabilizes the boundary between the “player” and the “game”, where parts of the player’s physical body become objects for agential intervention (hands too tight, too distracted with irrelevant thoughts, the eyes are not tracking well), and the partial connections between the “player” and the “game” become parts of the player subjectivity. This bodily agency challenges many aspects of narrative agency in the earlier part of the article. Indeed, Wardrip-Fruin (2020, p. 227) goes as far as commenting that the player has no agency in the core gameplay of rhythm games. Part of the reason is because transformation typically refers to only the game itself for narrative agency, while intention refers to the subjectivity of the player as encompassed within their physical body. But for bodily agency (see Figure 5), intention and transformation are abstracted. Both suggestion and transformation now refer to the same mechanism accountable for the hand-eye coordinated play. The difference between the two now becomes more analytical: transformation implies the changing of the player’s reaction through either new strategies or repetitive practices, while suggestion sees those reactions being carried out during gameplay. The transformation of the game state becomes trivial, while the player’s physical body is opened, its distribution made indeterminate, thus designating a different modality of agency. This conception of agency is related to a broader set of activities such as sports and performance art, detaching agency from its ludo-centric association.

By foregrounding the distribution within the player’s physical body as the main object of transformation, the physical act of “pressing a button” no longer merely designates the player transforming the game in a unidirectional manner. From the perspective of the game system, “pressing a button” means registering an input. In its simplest form, a button press can mean a binary trigger changing the game state. But with the player’s physical body in the picture, “pressing a button” does not merely mean what happens to the system afterwards, but also everything leading to the button press beforehand — the sight, sound, mechanics, and the body with all its orientations and volatilities. Keogh (2018) calls this “the convergence of audiovisuals with the mechanical foundations” (p. 111). In reaction-based play, audiovisuals also become part of the rules. Reflecting on my experience playing the game with my friends as a player-scholar, for example, I noticed the vastly different strategies we would adopt to beat the level. One of my friends experimented with focusing on different visual and sound cues to stay in rhythm, while I tried to sway my body to synchronize with the beats. A specific sound, a specific part of the screen, or a specific way the physical body moves can be determined accountable in achieving the play goal, without one reducible to the other.

Here, we can also consider the emergence of the player subjectivity, or intention, through a Deleuzian lens, as contraction of particles, or fixing of relations. Through strategizing and practice, the player eventually becomes attuned to the game, making hand-eye coordination more automatic and trivial, so the player can focus on aspects that pose actual challenges. Instead of describing this as the player “mastering” the game and their body, this contraction between the body and the game is an inevitable process of the emergence of a new subjectivity, consisting of human and nonhuman elements (e.g. screen-eye-hand-controller) coming together to form functioning and reliable parts, or perhaps cybernetic organs. This emergence of subjectivity in the hybrid player-game is well-explored in post-humanist game studies scholarship. Janik (2018) would apply the term bio-object to describe the player-game hybrid as a “qualitative new unity […] both the main conduit of the play’s meaning” (p. 3), while Hao would describe this as the player “co-becoming with games” (2023, p. 2). The experience of playing Rhythm Doctor engenders a particular way of rhythmic being, or becoming-rhythmic, through the player’s entanglement with the music, the visual and the sound cues, and their memories of the levels, to keep themselves in rhythm. One can imagine an altogether different dynamic/distribution when a different game is played, or when the player must play an actual instrument. All these factors are entangled in the player becoming rhythmic. The distribution within the physical body to be rhythmic — how their mind thinks, their hands move and their eyes perceive, is already contingent upon their connection with the outside.

This view of the player subjectivity that knows no boundary between the player and the game also adds complexity to the narrative agency from the beginning of this article. Having detached itself from the player’s physical body, intention can thus contain both actual desire of the player and the virtual desires of the avatar, both in productive relation to form an embodied ‘I’. Wilde (2019; 2023) also argues that this gamer-avatar subjectivity is already post-human. While narrative agency would conceptualize this movement as suggestion shaping intention, it does not capture the fact that for the player, the dynamics of agency has changed — the active ‘I’ has distributed itself over this player-game hybrid. As a result, the analytical language should shift as well. This also allows the ‘I’ to shift on the fly. In one moment, the player can take credit for the avatar’s action as an embodied whole, while in another, they can break away when the avatar behaves in ways that alienates the player. As Wilde & Evans (2019) put it, “the relationship is a continuous negotiation between the avatar and player, as the desires of one cannot be achieved without the actions of another, so that each part must be receptive to the goals of the other” (p. 803). This is the same logic as the bodily agency articulated here, where parts of the physical body are detached from the player subject and become objects to be intervened on and transformed.

Social Agency: Situating the Body

I have so far focused on the modality of agency in reaction-based play, where the boundary between the player and the game is destabilized. But play does not exist in isolation. Looking further outside the player-game unity, one discovers a larger player-game-social situation that determines how the game and the bodily agency come to matter and determine their distributions. Social Agency (see Figure 6) re-centers Fiske’s (1987/2010) social subject, where the player exercises agency over how much of the game matters to them according to their social needs.

I still term this social agency even if the player enjoys the game without interacting with other people, because the player still recognizes the game socially in terms of how the game matters to them. This question of how much the game matters conditions how the player exercises their agencies in reaction-based play, such as how much they are willing to practice to beat a level, or to achieve a certain ranking. This is a particularly interesting question for rhythm games, and Rhythm Doctor specifically. Against the ludic-centric understanding of play, both Keogh and Wilde argue for audiovisual engagement such as watching cutscenes to be considered “significant acts of videogame play” (Keogh, 2018, p. 130) and “[adding] to the agentic capacity of the assemblage” (Wilde, 2023, p. 139). This also describes the appeal of rhythm games as beyond mere mastery and, instead, centered on enacting the music, which constitutes a big part of the genre’s draw. In fact, one might not find mastery appealing without the immediate audiovisual enjoyment.

Rhythm Doctor is a good example on how this mixture of mastery and audiovisual enjoyment implies an intention that decides how much to engage with each aspect of the game. In addition to the music, Rhythm Doctor also offers visual performances that stand out from typical rhythm games. Each level tends to tell a story centered around the patients being treated. These design features make Rhythm Doctor a particularly fitting game for party settings. It engages with the audience interactively, visually and musically, both in focus and in the background. It is also a difficult game. The player needs a B rank to access the next level, and an A+ rank to access a secret night level. How much continual practice on a single song thus becomes a social choice. One can decide to see all the levels first, or to try to perfect a single level, both of which differ in how the bodily agency in reaction-based play matters for the enjoyment of the game.

This social agency can also condition bodily agency in a more non-obvious and passive way, as in, the social setting inevitably changes the dynamic/distribution of the body. Knowing others are looking, playing the game for a specific person, or simply just playing by oneself on a specific day can pose different configurations and challenges for the player. Even without the player’s conscious knowledge, the factors outside the player-game unity are already entangled and conditioning the particular distribution within that unity. Social agency captures the surfacing of that realization, to hold particular factors outside the player-game to be accountable and to inform intervention (“Should I play alone? Am I sitting wrong? Should I wear headphones or play without sound? Should I stream and record my play?”).

“Get Good”

So far, the two modalities I have presented are derived through the same infrastructural approach; the bodily agency would reveal the shifting distribution within the player’s physical body (looking inward) as contingent upon the player-game unity (looking outward), while the social agency would reveal the distribution within that unity as contingent upon the social. This section focuses on a particular discursive practice that determines how previous modalities come to matter. I derive this discourse from a particular strand of popular gaming culture that sees the primary video game enjoyment to be mastering game mechanics and overcoming challenges. I would like to simply term this discourse as ‘get good’. Scholars have connected this discourse to the historical development of hacker culture (Keogh, 2018, p. 180), and to neoliberal subjectivity (Muriel & Crawford, 2020). Nevertheless, the ‘get good’ discourse still holds power in normalizing particular ways of play and shaping social expectations within gaming culture.

The ‘get good’ discourse also surfaces a particular modality of agency, thus a particular distribution of accountabilities. This modality has two characteristics. The first is the over-determination of observable, countable and measurable metrics. This is exemplified by parts of the game like rankings, hit/miss ratios or scores overpowering the other parts, such as audiovisual enjoyment, to determine a level of ‘competency’. The second is the over-determination of accountability for the player as a stable, individualized subject. Reaching a normalized marker of success would be the player’s primary responsibility. This structure of accountability would cast both bodily agency and social agency as serving a particular end. By discussing the “Battleworn Insomniac” levels of Rhythm Doctor, I would like to offer an infrastructural view that challenges this discursive over-determination.

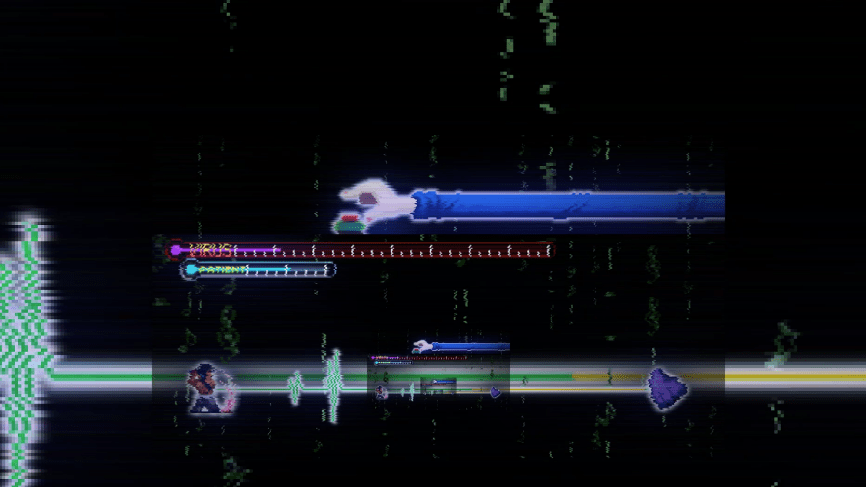

Due to the virus “Connectifia abortus” infecting the player character’s connection, the level introduces glitchy effects during play: visual cues skip, the music pauses, the whole screen distorts into color blocks and noises. The level’s harder variant, which introduces irregular time intervals mid-level, has the screen continuously zooming in (see Figure 7), which noticeably makes the player dizzy. The level also uses noise to obscure the beginning of each measure, meaning that the player must consistently keep track of the beat between each seven-beat measure rather than simply counting to seven when the music cues the start of the measure.

Through their design, the levels ask implicitly ‘how does one keep rhythms?’. By slowly taking each cue away, or making the cues actively obstructive, the levels demonstrate how the player had relied on so many external signals to track rhythm – a contraction/fixing of relations already building through subconscious repetition. But the rhythm can be kept in many ways, and indeed, many bodily strategies are possible – foot-tapping, head-shaking or mouth-counting. Upon player’s failure, the game suggests “drumming on a table in ‘seven-eight’ time” – referencing the time signature of seven eighth notes each measure. Comments under the gameplay video also suggest different approaches such as “closing my eyes” or using “left hand as metronome” (1-XN, 2021). By disrupting established play habits, the levels reveal a vast possibility space in re-attuning the body to beat the level, showing how players exercise their bodily agency differently.

Because video games often normalize success through explicit structures such as levels and scores, it is intuitive to frame these strategies as humanistic mastery towards the system and the body itself. But such framing would be too localized to the human actor in play, already over-determining accountabilities in the player entity and its intention. Why does a certain strategy, as a particular distribution of the player-game unity, work for a player? How did they produce them in the first place? These questions necessarily lead to examining factors outside the player’s intention and the immediate play situation. It is helpful to understand these play strategies as ‘learning’ in a Deleuzian sense. To Deleuze (1968/2014), learning is distinct from knowledge. In short, while knowledge supposes a “a rule enabling solutions” (p. 213), learning is the encounter with problematic fields that are “not simple essences, but multiplicities or complexes of relations and corresponding singularities” (p. 212). This is why Deleuze believes learning is not a reproduction of knowledge, but involves difference, where “distinct points renew themselves in each other” (p. 27).

An entanglement of matters is implicated in this act of learning as an encounter with a problematic field. As a one-button game, Rhythm Doctor allows a wide range of input devices and button presses. Holding a controller, resting the hand on a keyboard or a mouse, deciding to press a button or a trigger, all have different consequences to how the player’s physical body adjusts to the gameplay. The player’s play setting and their social history (including their familiarity with musical performance) are all factors determining the level of challenges for the player. Even the physical body’s particular tendencies and volatilities are shaped by its histories. Why certain bodily strategies work must be understood in this vast array of material, social, cultural and psychological contingencies. This is why Deleuze (1968/2014) says “it’s so difficult to say how someone learns” (p. 27). These factors are what constitute ‘learning’ as production of the new, as fundamentally involving differences. No two moments of play are reducible to each other, as the heterogeneous and entangled factors involved already make them incommensurable. The ‘get good’ discourse is thus in distinct contrast to this understanding of reaction-based play, as an affirmation of differences that are necessitated by the player’s entanglement with the world. A bodily agency directed towards reasoning about the physical body already must confront the present and the past that shape that very body. Simply put, to understand oneself is to be entangled, and thus, post-human, or in Barad’s (2007) words, “we are a part of that nature that we seek to understand” (p. 26).

Conclusion

Agency is always distributed, and it has always been uneven, fluctuating and volatile. I argue for an understanding of agency as contingent upon the construction of entities and their relations, which designates a distribution of causal power and accountabilities. Taking an anti-essentialist and post-humanist perspective, as influenced by Barad and Deleuze, I propose an approach to reveal the constructedness of these entities and relations, and thus enabling a way of envisioning their contingency and fluidity. This approach sees a stabilized entity as having a particular distribution within itself that is capable of newness by not taking it for granted (through Deleuze), and each stabilized distribution is already fixed through material-discursive practices outside itself (through Barad). This approach can enable us to derive more modalities of agency, as seen through my case study of Rhythm Doctor. If any determination of entities, relations and structure is already entangled, then any localized entity is understood as infrastructure to those determinations, as directing the flows without dictating its results. This is the metaphor I apply to video game’s relation to agency. While one can certainly focus on agency through game rules, it is a particular determination committed to a material-discursive practice that should not be taken as a given.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank my advisor Noah Wardrip-Fruin for the extensive feedback throughout the earlier versions of the article, my colleagues at the EIS lab for reading and providing feedback, and my advisor Michael Mateas for the early conversations. I also want to thank the reviewers and editors for their invaluable insights and guidance.

Author Biography/Biographies

Hongwei (Henry) Zhou is a Ph.D. candidate in Computational Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His research interests combine his training in computer science to inform game criticism and design, spanning the field of game studies, software studies and artificial intelligence. Two of his most recent works include critiquing computational practices through social critical theories and exploring the phenomenological implications of artificial intelligence.

References

1-XN super battleworn insomniac (2021). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbAqdNv5nF4

7th Beat Games. (2021). Rhythm Doctor. PC: 7th Beat Games.

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annual review of anthropology, 30(1), 109-137.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Duke University Press.

Braidotti, R. (2013). Posthuman humanities. European Educational Research Journal, 12(1), 1-19.

Bódi, B. (2023). Videogames and agency. Taylor & Francis.

Boluk, S., & LeMieux, P. (2017). Metagaming. University of Minnesota Press.

Carstensdottir, E., Kleinman, E., Williams, R., & Seif El-Nasr, M. S. (2021, May). “Naked and on Fire”: Examining Player Agency Experiences in Narrative-Focused Gameplay. CHI 2021, 1-13.

Daigle, C., & Hayler, M (2023). Theory into praxis. Posthumanism in Practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Deleuze, G. (2014). Difference and Repetition. Bloomsbury. (Original work published 1968)Eichner, S. (2014). Agency and media reception. Springer Science & Business Media.

Fiske, J. (2010). Television culture. Routledge. (Original work published 1987)

Fizek, S. (2022). Playing at a Distance: Borderlands of Video Game Aesthetic. MIT Press.

Freeplay Parallels. (2020). Umurangi Generation. YouTube. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgVhQVTxXQg.

Girina, I., & Jung, B. (2019). Would You Kindly?. The Interdisciplinary Trajectories of Video Game Agency. G| A| M| E Games as Art, Media, Entertainment 8(1), 5-28.

Giddings, S. (2007). Playing with nonhumans: Digital games as technocultural form. In DiGRA 2005.

Hao, Y. (2023, June). Toward An Agential Realist Account of Digital Games: Revisiting Gamic Agency and Materiality. In DiGRA 2023.

Imbierowicz, E. (2023). Posthumanist Attitude Towards Animals in Digital Games. In DiGRA 2022.

Janik, J. (2018, August). Game/r-Play/er-Bio-Object. Exploring posthuman values in video game research. In Proceedings of The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Vol.1, 1-8.

Jennings, S. C. (2019). A meta-synthesis of agency in game studies. Trends, troubles, trajectories. G| A| M| E Games as Art, Media, Entertainment, 1(8).

Keogh, B. (2018). A play of bodies: How we perceive videogames. MIT Press.

Mateas, M. (2001). A preliminary poetics for interactive drama and games. Digit. Creativity, 12(3), 140-152.

McKeown, C. (2019). “You Bastards May Take Exactly What I Give You”: Intra-action and Agency in Return of the Obra Dinn. Game: The Italian Journal of Game Studies, 8(1), 66-85.

Murray, J. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck. Free Press.

Muriel, D., & Crawford, G. (2020). Video games and agency in contemporary society. Games and Culture, 15(2), 138-157.

Millington, B. (2009). Wii has never been modern. New Media & Society, 11(4), 621-640.

Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Games: Agency as art. Oxford University Press, USA.

Ninendo EAD. (2007). Wii Fit. Wii: Nintendo.

Petris de, L. & Falk, A. (2017). (Re)framing computer games with(in) agential realism. In The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Kraków 2017

Rockstar Games. (2010). Red Dead Redemption. Multi-platform: Rockstar Games.

Ruberg, B. (2019). Video games have always been queer. NYU Press.

Ruffino, P. (2020). Nonhuman games: playing in the post-anthropocene. In Death, Culture & Leisure: Playing Dead, 11-25.

Stang, S. (2019). “This action will have consequences”: Interactivity and player agency. Game studies, 19(1).

Tanenbaum, K., & Tanenbaum, T. J. (2009). Commitment to meaning: A reframing of agency in games. Digital Arts and Culture.

Tanenbaum, T. J. (2011). Being in the story: readerly pleasure, acting theory, and performing a role. ICIDS 2011, Proceedings 4, 55-66.

Telltale Games. (2014). The Wolf Among Us. Multi-platform: Telltale Games.

Wardrip-Fruin, N., Mateas, M., Dow, S., & Sali, S. (2009, September). Agency Reconsidered. In DiGRA 2009.

Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2020). How Pac-Man eats. MIT Press.

Wilde, P. (2023). Posthumanism in play. In C. Daigle, & M. Hayler (Eds.), Posthumanism in Practice (pp. 133-146). Bloomsbury Academic.

Wilde, P., & Evans, A. (2019). Empathy at play: Embodying posthuman subjectivities in gaming. Convergence, 25(5-6), 791-806.

Wright, E. (2022). Rockstar Games and American history. De Groyter Oldenbourg.