by Yaochong, J. Yang

Published December 2024

Download full pdf of article here.

Abstract

This paper focuses on Crispy’s! and Japan Studio’s Tokyo Jungle (2012) as a limit test on the procedural rendition of nonhuman engagements through the language of anthropocentric semiotics. Here, I draw on Ian Bogost’s (2006) definition of the simulation, or the gap between the rules-based representation and its source system. Along those lines, Tokyo Jungle, a game concerning animals in a world where humans have suddenly disappeared, simulates post-apocalypse along two relevant levels. Firstly, it is a game concerned about playing in a world after humanity. Second, it is dedicated to playing that world through nonhuman subjects. There is, consequently, a double folding of the apocalypse lens; not only is it simulating a world beyond human dominion, but also where its inheritors are critically nonhuman. Here, Tokyo Jungle serves as a crucial transitional text, employing what Quentin Meillassoux (2008) defines as correlationism—an insistence on a subject’s incapacity to surpass its consideration—to present alternative pathways beyond its correlations. In other words, it employs anthropocentric dramas and semiotics to form an affective core that gives meaning to its rejection of the Anthropocene. Tokyo Jungle accomplishes this by interlocking its Survival and Story Modes, forming a ludic emotional loop which depicts a posthuman world via access by consequence, mapping out what Donna Haraway might consider a tentacular approach to human effects on nonhuman subjects in relation to a system (2016). I focus on how the game does not present post-anthropocentric orders as extant to human understanding, but rather leans on human-like narrative conventions to inform the dramaturgy of its animals. The liminal presentation of Tokyo Jungle’s post-apocalypse is at the core of its procedural argument, in that it does not ignore human influence, but integrates and implicates human influence as part of its examination of nonhuman subjects. In other words, the game does not deploy human-like qualities simply because it cannot envision meaningful behaviours beyond humanity. Instead, it reifies such qualities to reflect the simulative gap between its nonhuman source system and the rules its human developers have created.

Keywords: Tokyo Jungle, Donna Haraway, oddkin

Introduction

In a photo article by National Geographic, author and photographer Manabu Sekine (2021) recounts a visit to the Japanese village of Iitate. Abandoned in 2011 after the Tohoku tsunami and Fukushima-Daiichi meltdown, Sekine’s subjects focus less on the lived spaces of its former inhabitants, but its new ones: blooming rhododendrons, skittering rabbits, boars, and foxes navigating walls of tar-black bags full of radioactive soil. Douglas Main (2021) describes Sekine’s photography with the language of reclamation: the animals have “moved in”; they’ve “reclaimed.” The consequence of the Fukushima-Daiichi meltdown, the costliest manmade disaster in human history (Lloyd Perry, 2017, p. 12), is the mass removal of people and the reinvigoration of nonhumanity.

In 2012, Japanese game studio Crispy’s! released Tokyo Jungle on the PlayStation 3. Tokyo Jungle is a sci-fi survival-action game where players play as animals in the heart of Tokyo. Humans—all humans—have disappeared. The game is split into two interlocked modes: a “Story Mode” focusing on vignette-style tribulations of specific animals, and a “Survival Mode” where you explore parts of the city to find USB archives that hint at why humans disappeared. Each species has different move sets, styles, and needs. All of them replenish their health via a hunger mechanic. Carnivores hunt other animals and herbivores graze.

This article focuses on Tokyo Jungle and its use of procedural and semiotic systems to simulate alliances. It uses these systems in a post-Anthropocentric setting, which this article colloquially summarizes as an era beyond human control. Though the post-Anthropocene is also deeply engaged with visions of what Esther Priyadarshini (2021) might call temporal imaginaries of utopia, revolution, and pedagogy (p. 3-4), what constitutes those visions and how they inform the ontology of apocalypse is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, this article’s primary focus is on the manifestation of what Priyadarshini (p. 4) and Haraway (2016) both agree are hallmarks of the post-Anthropocene: a possibility of corrective visions beyond distinctly personal, neoliberal, humanist frameworks and towards directional analyses of worlds as relations of relations, where such entanglement is what sets in motion a world without human control (p. 47). In post-apocalyptic games, such entanglements are often reflected at the seeming expense of its human characters, suggesting that the post-apocalyptic alien space is innately hostile. It is why many post-apocalyptic games lean on one of two general perspectives: the world without human dominion is dangerous, or we are squandering what we had. However, I argue that Tokyo Jungle presents a different vision of the post-Anthropocene through its nonhumanity, specifically what Haraway (2016) calls a tentacular approach to systems of representation (p. 31). This approach is important as Tokyo Jungle uses these procedural and semiotic relations not out of an insufficiency to examine a posthuman order, but to demonstrate the post-Anthropocene as an interimplicated zone, a site where humans and nonhumans are defined not by their ontological status, but by the relations that exist between them. This is clearest through three elements in Tokyo Jungle: its limits as an ecocritical game, its emphasis on compost-like relations of human traces, and its status as a form of anti-apocalypse. All three demonstrate the same core element at play: the reification of alliances to reflect relations between human players and its nonhuman source system.

The Role of the Nonhuman as Points of Alliances

Before discussing the game, it’s important to discuss the specifics of animal subjectivity, the subject of which has been a mainstay of scholar Donna Haraway. To Haraway (2016), animals are a form of oddkin, or subjects formed from unexpected interactions and collaborations, traversing beyond frameworks of fixed loci onto relations in motion alongside a multivalence of beings (p. 4). Haraway’s largest singular foray into companion species work was her 2008 book When Species Meet, where she suggests a reconsideration for human-animal relations, not as domination but a set of invitations between subjects, namely, humans and dogs (2008, p. 27). Here, Haraway seeks to bring into analytical clarity what she deems “the daily, the ordinary, and the affectional rather than the sublime” (p. 29). The dog, to Haraway, presents a subject whose relation to human beings is not something managed or controlled, but with a gravitational force of its own; just as humans affect animals, animals affect humans. The dog inhabits a unique place in Haraway’s discussion, being the first animal humans domesticated, emblematizing “dogs and people…as [emergent] historical beings, as subjects and objects to each other, precisely through the verbs of their relating” (p. 62). The goal of Haraway’s posthumanist perspective through animals is not to make the seemingly inaccessible now accessible, but rather to expand on relations between subjects as new grounds of subjectivity. This sense of the subject as something interconnected through interactions is the baseline of Haraway’s approach to animal-centric worlding.

However, while the dog presents the baseline for Haraway’s discussion on posthuman subjectivities through alliances, her work on pigeons—the animal humans domesticated and then subsequently ejected from our sphere of domestication—demonstrates how political, social and economic forces linger as traces (2016, p. 18). They form the core of what Haraway refers to as a potential without futurity, a set of conditions of relations exploded outwards without answers. The pigeon is not merely a species, Haraway argues, but a species of codomestication and empire, one which humans built around (and built their empires around); now that pigeons have been replaced with technological developments, they are “returned” to the wild (p. 19). Yet, as Haraway notes, pigeons did not simply return, but have become a permanent species of alliances, a set of subspecies whose longstanding evolutionary traits bear the imprints of (an)other: humans.

In this sense, Haraway (2016) introduces a useful perspective on understanding animals as subjects whose behaviour consists of connections between their conditions and our relation to them. The heart of Haraway’s critique of the Anthropocene is its hegemonic position: speaking of the end of a human-led order is to speak on the conditions of human subjectivity. The Anthropocene, Haraway suggests, is more akin to a Capitalocene, the end of an order led by a specific political class of human, a privileged global North dominated by an often bourgeois intellectualism (p. 49). To everyone else, the end of what we might call the “Anthropocene” has begun long before, externalities of the decisions of the well-off and landed, who might only be speaking of alarm bells now. To Haraway, “we” (meaning people who have the time to read this) are witnessing a shift now that has long been witnessed by indigenous peoples (p. 49). Conversely, with many of us in the process of the “game-over” mentality, Haraway also warns us that the end of the Anthropocene is not necessarily a universalist proposition.

Humans are Haraway’s (2016) Capitalocene and Quinby’s (1994) hegemonic masculinist perspective (which I will return to shortly). The animals, on the other hand, are the tentacular subjects comprising what Haraway (2016) calls the Chthulucene, the subjects constituted by the performance of material meaning in cosmic processes (p. 2). Haraway uses “tentacular” to refer to a form of subjectivity defined separate from the reflective analysis of its subjectivization, a sort of subjectivity by virtue of its consequences. To Haraway, the role of tentacular thinking is an emphasis on lines in motion, with less focus on determinisms and more on processes defined by travel, honing in on Haraway’s insistence that such thinking is to move, navigate, and try (p. 31). This tentacular thinking suggests that animals do not register the apocalypse. This is at the heart of Haraway’s discussion on alliances: people and animals are entangled in the sense that relations are determined by a longstanding set of reproducing interactions where neither side is dominant nor inaccessible.

This focus on animals as constitutive of alliances between people, especially as a window into non-Anthropocentric visions of apocalypse, helps shed light on how even apocalypse behaves as a perspective machine. In other words, animals remind us to be skeptical of the end of the world, as what constitutes the end of the world is always bracketed by questions of whose world. This skepticism of apocalyptic scope is a form of anti-apocalypse, a perspective presented by Lee Quinby (1994), who argues that apocalypse is more of a regime of truth rather than a coherent, absolute belief (xv). Quinby was writing specifically after the wake of 1980s America, in the resurgence of the Pat Robertson fundamentalist movement and the explosion of the millenarian movements beginning in the 1970s. Core to Quinby’s thesis is that apocalypse is a site of enactment which specifically limits freedom and movement, and that the existence of political radicalism indicts pre-existing relations of power (xxii). To Quinby, apocalyptic visions frequently assail feminist work and women’s bodies in general; the division of feminist movements into epochal shifts (First, Second, Third, and Fourth Waves) has given ammunition to patriarchal structures that pronounce and employ an end of history rhetoric, that finally now (and always now) women and women’s bodies are finally able to do things (p. 35). Yet Quinby simultaneously stresses that apocalypse is also relational; feminist discourse employs apocalypticism (dismantling masculinism and patriarchy), but the ends it seeks are different (p. 36). In other words, apocalypse always comes with an asterisk: to whom?

Haraway (2016), in some instances, is similarly skeptical of apocalypse, but applies it to human-animal subjectivities. Haraway echoes Quinby in that apocalypse is perspectivalist, that certain groups are always speaking of apocalypse while simultaneously insisting on the universal totality of its effects. The force of Haraway’s alliance-oriented approach is a bulwark against what she deems the surrendering nature of apocalypse, that “we think we know enough to reach the conclusion that life on earth that includes human people in any tolerable way really is over, that the apocalypse is nigh” (p. 4). Yet in Haraway’s animal version of anti-apocalypse there lies another challenge, in that animals don’t speak with humans the way other humans can. It is here, Haraway would suggest, that the role of alliances—and how interimplicated relations of engagement lead to strategies of coherence—becomes vital.

I suggest that Tokyo Jungle is the stage upon which Haraway’s discussions of alliance is at its most striking.

What is Tokyo Jungle and What is it Doing Differently?

What differentiates Tokyo Jungle from many other post-apocalyptic games is that it does not depict humans in any direct capacity, yet simultaneously tackles a crucial issue at the heart of playing nonhumanity: depicting and engaging with nonhuman subjects in a way that is legible to a human audience. At the same time, the game enacts a play space where human influence remains deeply consequential. A sci-fi survival-action game, Tokyo Jungle has you play as animals, ranging from Pomeranians to Dilophosauruses. What differentiates Tokyo Jungle, and specifically its depiction of animals, from other forms of non-human apocalypse (such as androids and robots) is its explicit rejection of the role of human creators, specifically in that people are hardly the dramatic crux of the game. The game does not present said animals as byproducts of humans, but rather a seemingly sapient set of species whose relation is affected by—but not determined by—humanity.

The game is split into two modes: a challenge-based Survival Mode, where players accomplish objectives as specific animals, and a Story Mode, a collection of intertwining stories focused on specific animals. The disappearance of humans is the guiding mystery: players must play both modes to completely unlock the story. To proceed in Story Mode, players must complete challenges in Survival Mode. Through this process, the animals of Tokyo Jungle never make contact with any humans, setting in motion an iterative process that propels the mystery of the game while ultimately emphasizing the consequences of human action.

Most game time occurs in Survival Mode, where players not only cycle through progressively challenging scenarios in open-world engagements with enemies but are also given the most freedom to engage in ways akin to animals. It is the game’s open-ended core: players tinker and experiment with groups, can engage in co-operative play, and are given few objectives. As players unlock more scenarios, they unlock more animals, and with more animals, they unlock even more scenarios. In Survival Mode, animal lifespan is reflected by a year counter, where each successive year increases the hunger requirement. As years go by, enemies will become increasingly dangerous and satiating hunger becomes less effective. Therefore, players are incentivized to reproduce their genes, creating maps of successive generations in Survival Mode. In Survival Mode, much of Tokyo is explorable from the beginning. Some exceptions include areas locked behind animal sizes and the underground laboratory locked behind a chapter in Story Mode. To unlock further chapters, players need to find “archives,” items with snippets left behind by humans. Tokyo Jungle’s gameplay loop consists of finding USB sticks, and doing so requires buying as much time as possible. In Survival Mode, time is the most important resource: if players wish to proceed further into Story Mode, they need to find objects, and that requires time. To get more time, they need to engage in specific actions: breeding offspring, taking over territory, and outcompeting the established fauna. In other words, success in Survival Mode—unlocking further stories—is achieved by learning how to behave like an animal.

The consequence (and irony) of Tokyo Jungle’s Survival Mode is that an animal’s goal to reproduce and survive is both reflected and problematized through similar discussions on human struggle through the game’s neoliberal rhetoric. As time goes on, players will eventually be outcompeted by tougher and tougher enemies, resulting in an inevitable loss in Survival Mode. In other words, humans (and human players) are not dissimilar from animals in that the stories players engage with in Survival Mode are alien, but at the same time, humans (both diegetically and player humans) cannot solve the problem of the mass disappearance of humans in the plot; the game is careful to avoid anthropocentric sutures of issues which have emerged in the post-Anthropocene. The inevitability of death in Survival Mode indicates how Tokyo Jungle employs its procedural rhetoric to present its entanglement, specifically by interlocking animal and human survival as it is perceived by players as similar dead ends. For the former, the inevitable loss in Survival Mode can be seen as a form of meta-critique, somewhat of an acknowledgment that as players progress, there is no anthropocentric “solving” which makes them any more equipped to tackle the post-apocalypse. For the latter, humanity’s role is written more directly, demonstrated when players unlock further Story Mode chapters.

Finding USB drives unlocks more chapters in Story Mode. Here, you play as tamed or domesticated animals finding themselves stuck in a new environment. Among them are a pampered Pomeranian compelled to produce offspring, a lost fawn who must avoid predators in search of their mother, and a lion, exiled from his pride, back for revenge. Most of the arcs are supplementary to the game’s core mystery; the back-and-forth turf warfare where animals jockey for power does not affect the outcomes in the story. While Survival Mode is very open-world, the story chapters have largely true-false mission criteria, with most adopting the level design of platformers; the only thing that matters is that the objectives are completed.

Story Mode concludes with the trek of an electronic dog, ERC-003, whose task is to activate an unexplained protocol to return the humans back to Earth. It turns out that in the indeterminate future, Earth has run out of resources and become polluted beyond repair. Future humans (whom the player never encounters) have devised a means of saving themselves: replacing their position within the timeline with past humans, effectivelyswapping positions with their predecessors. However, something goes awry with the displacement, and ERC-003 is tasked to fix the error. In the final mission, which is also the only mission that affects whether players receive a “good” or “bad” ending, the player (as ERC-003) is given a choice to either bring humans back or leave them stranded in the future. Should the player comply with the request to bring back the humans, ERC-003 goes into cryostasis and the game resolves unsatisfactorily, specifically in that the game directly goes to credits. If the player refuses, they must then defeat the other robot dogs, trigger a self-detonation sequence, and escape. The “good” ending concludes with a deactivated ERC-003 overgrown by plant life, and the player is rewarded with a cutscene which elucidates the continued prosperity of the animals.

Tokyo Jungle is both a compelling and mystifying case study on the post-Anthropocene specifically because it rejects the return of human actors but still employs idiosyncratically human drama as the core of its characters. The animals are hardly presented as distinct alien objects, but as animal-like humans, up to and including dressing and behaving like humans. This halfway identity is important considering that the game is a simulation. Here, by simulation I refer to Ian Bogost’s (2006) definition, a gap between rules-based representation and what Bogost calls a “source system,” which can be many things: a phenomenon, a concept, or an object (p. 107). The game contends with two source systems. One is crafting a simulation of a world beyond human dominion, especially the exploration of what that might entail. The second is a meta-challenge, specifically in terms of how to relay animal motivations and behaviours in a way that connects to human players without simply becoming humans dressed up as animals.

In this sense, Tokyo Jungle employs a somewhat archaeological imagination of apocalypse by inverting the core challenge of nonhuman engagement: access to the subject outside of human language. Understanding nonhumanity requires grappling with subjects with limited ways to speak back. In many post-apocalyptic games, these take on what Andrew Reinhard (2018) describes as the process of accumulating and understanding trace material to make a specific period and location intelligible (p. 3). To be fair, Reinhard’s definition of archaeogaming extends beyond digital environments and objects, but into a game’s metadata and extra-digital substrate, including the platforms on which these games thrive. However, archaeogaming can also describe a reinforcing loop in player engagement with the post-Anthropocene: an acquisition of times long past. A selling point of post-apocalyptic games is their traces, the remnants left behind from previous eras. Access, in this context, refers to access across time; there was “another” time that players make sense of through navigating the post-Anthropocene.

Indeed, Tokyo Jungle’s most notable contemporary (in terms of publishing date, subject matter, and publisher)—Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us (2013), in which a mutated fungus has destabilized human society—bears a mid-level archaeogaming substrate. In The Last of Us, players play as Joel, a survivor from before the apocalypse, and during their travels Joel recounts preapocalyptic America to Ellie, who was born after the apocalypse and has no personal experience with most of the institutions Joel recounts. In comparison, Tokyo Jungle attempts to situate archaeogaming practices more closely to its core. It is not only concerned with understanding a world beyond apocalypse, but also through subjects that, in many ways, have neither the access nor language to understand the conditions of that apocalyptic event. In many post-Anthropocene games, traces are intelligible specifically through the explanatory language of the game: items, characters, and monuments act as totems that clarify the process of the post-Anthropocene. In Tokyo Jungle, the animals have no capacity to even learn of post-Anthropocentric apocalypse: they do not suddenly learn to read, write, or interpret human language. Though players can read said USBs, the player interaction with these USBs and the animals’ seeming drive to collect marks a point of irreconciliation between the human player’s need to make the drama intelligible and the animal’s distanced relationship to these logs. In other words, collecting USBs connotes apocalypse as a tunnel of continuation between Anthropocene and post-Anthropocene, and despite its name, the post-Anthropocene remains interimplicated by the Anthropocene.

The issue at hand in Tokyo Jungle which sets it apart from many of its contemporaries is an issue of access. Tokyo Jungle is an inversion of the human relation to animals: just as animals are inaccessible to humans through language, humans become inaccessible to animals through spacetime. Access, both Bogost and Meillassoux note, informs the means in which we engage with nonhumanity specifically by reason of what Meillassoux (2008) considers its originary logic, specifically that something exists because it is tied to questions of coherence (p. 7). Along these lines, Tokyo Jungle can seem correlationist in that the animals undertake the trappings of anthropocentric behaviours and clothing as a form of access (even though they never interact with humans): for players to feel for these animals in these ways, they must act like us. In fact, the game equates the “animal order” as not entirely dissimilar to a human one: the concrete labyrinth of Tokyo is described as a jungle, both figuratively (as winding and difficult to navigate) and literally (as covered in overgrowth). Hierarchical stratification bears a resemblance to a sort of neoliberalism, which Anne Allison (2013), referencing David Harvey (2011), typifies as deregulated relations of increasing precarity, competitive navigation of the socioeconomic order, and an upholding of the market over the security of the people (p. 53-54). In reference to fictional survival games, Motoko Tanaka (2014) argues such visions are couched in real economic precarity: the “neo-liberal structural reforms…led by Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi,” led to an aggravation between rich and poor, of life-threatening games where society is “either totally unreliable, [or] amoral, dystopian, and irrational, a place where virtue and ethics have no meaning.” Tokyo Jungle reflects these sentiments: the ending of the tutorial describes the world as neither pleasant nor harmonious, but as a “struggle for survival,” that “the fight to survive is never easy, but only victors live to see where the future lives.” Animals can thus be seen as a sort of visual scaffolding, by which I mean the game seems to present a combat-oriented survival game, but one where the characters are animals. Here is the first line of tension: Tokyo Jungle focuses on animals after humans have disappeared, but the game was written, developed, and published by humans. This can seem like a trite observation, but it’s an important factor: if the representation of nonhuman subjects is embedded in a culture dictated by humans, then playing as nonhuman is always ideological, in the sense that assumptions on relations inform the relations of the subjects we play as. The conclusion of this argument is of the Anthropocene as a totalizing structure: even in a world without humans, animals are left to the devices of humans.

However, I argue that Tokyo Jungle is less focused on carving out an explicit pathway of envisioning the post-Anthropocene, but rather relays visions of relations between human and nonhuman subjects. Here is where Haraway’s (2016) conception of alliances, referring to relations between knots of relations, comes into play (p. 207). The game does not present simply humanlike animals or an anthropocentric ideology in its depiction of subjects still existing in the post-Anthropocene, but rather focuses on subjects constantly in transition between poles of engagement, between Anthropocene and post-Anthropocene. In Tokyo Jungle, animal struggle is dramatized through the lens of human struggle: the brave new order (which the game directly states) and scrounging of USB sticks foregrounds the human player’s perspective, even as the game takes great pains to distance its animals from any in-game human interactions.

Is Tokyo Jungle an Ecocritical Game?

Though Tokyo Jungle is sometimes associated with the ecocritical subgenre (Backe, 2017, p. 48), the game’s anthropomorphizing of animals as well as limited overall set of pedagogical conclusions on nonmaterial phenomenology place it somewhat within the genre’s borders. Ecocritical games tend to be defined by a focus on nonhuman materiality and “bringing in” nonhumanity into frameworks of analytical clarity (Chang, 2019, p. 134) through systemic reactivity (Condis, 2020). In other words, ecocritical games tend to make nonhumanity accessible, to craft lanes of empathy with the aim of decentering human subjectivity (Chang, 2019, p. 134). However, these ecocritical discussions have a somewhat pedagogical focus: through engaging with the system, players develop strategies to make sense of relations of existence with their environments, which are oftentimes natural (Thibault et al., 2022). Hans-Joachim Backe (2017), in a meta-analysis of ecocritical games, typifies them as machines with avenues for potential discourse, specifically by virtue of engaging with environments as a critical viewpoint, especially concerning questions of the Anthropocene. More specifically, he notes that “formalized games of strongly ludic character…tend towards a mechanistic treatment of their subject matter,” and since these games “are characterized by the construction of complex, yet calculable systems with many discreet [sic], unequivocally defined elements,” players have often ended up seeing them as planes of mastery (p. 43). In other words, the inherent digitization of conceptual rules in the medium of the digital game always bears a tension played out in discussions of the Anthropocene: all of nature is subsumed into the mastery of the (human) player. Through this lens, the strength of the ecocritical game genre can be a form of hijacking, to use such systems to shape new, alternative pathways of empathy with nonhuman subjects through systemic representations. Furthermore, the end goals are usually didactic: players realise such strategies through play and learn how they relate to natural environments through virtual engagements.

In comparison, Tokyo Jungle stands at the margins due to two distinct differences. One, the game is limited in its pedagogical capacity. The game does not depict its animals as freed from humans, but rather as successors. It does not demonstrate much about the role of humans nor give any solutions on how to fix the world compared to more orthodox ecocritical games like Thatgamecompany’s Flower (2009). In Flower, the player plays a flurry of petals gliding through dull grey environments. As they hit specific markers, these spaces become more colorful. Later, certain spaces—that of twisted industrial infrastructure—become nearly impossible to colorize. Flower’s gameplay suggests the effect of human industrial engagement in that returning to a verdant natural environment becomes much more difficult the more embedded structures there are. In Tokyo Jungle, these critiques are largely missing: outside of the USB archives, which give context on the world before the apocalypse, humans have functionally little active voice. While human systems exist (after all, the entire game takes place in Tokyo), the animals engage with them as extensions of a presupposed natural order. It is only at the end with ERC-003, a robotic dog built specifically to bring humans back, that the game’s animals acknowledge human structures as distinctly human constructs.

The second difference is that Tokyo Jungle’s characters are not natural, distancing the game from reclamation and more towards lanes of interimplicated subjectivity. Aside from a few exceptions, most of Tokyo Jungle revolves around either domesticated animals or animals alien to its environment. The first Story Mode animal, and the animal that it most heavily advertised in its marketing, is the Pomeranian, a “toy breed” that must learn to be feral. In fact, almost all of Tokyo Jungle’s Story Mode animals are either non-native or domesticated: players play as hyenas, lions, beagles, and Tosas, all of whom have escaped human confines of apartments or zoos. These two differences, the non-natural condition of its animals and the lack of clear ecocriticism in its gameplay, set it apart as a game of alliances.

Tokyo Jungle as an Interimplicated Apocalypse

Tokyo Jungle’s survival and Story Mode work in tandem to express its worldview that nonhuman subjects help humans understand apocalypse through nonhuman relations with us, not as objects, but as other subjects. Yet more specifically, these other subjects are not those in tension with human societies but formed directly from the human-nonhuman relation. The vision of a “reclaimed” space after the Anthropocene is one suggested by Kathryn Hemmann (2018), who frames their analysis of Tokyo Jungle through Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us (p. 81). Game director Yohei Kataoka (2013) expressed similar intentions: he was influenced by Nakano Masaaki’s Tokyo Nobody (2000), a collection of photographs of Tokyo without people. The premise of a world without humans, therefore, suggested a world of reclamation, of new animal semiotics (Kataoka, 2013). Indeed, the development team took great strides to avoid overt human influences. For instance, music producer TaQ (Sakakibara Taku) stated that, despite the jungle-like atmosphere of drums, they avoided using them since they were made from the hides of animals (Hemmann, 2018, p. 81). A drama without humans, Hemmann and Kataoka note, is core to Tokyo Jungle.

This relationship forms the game’s core loop: players cannot proceed through one mode without playing through the other. Players collect artifacts in Survival Mode, with each artifact explaining snippets of humans before their disappearance. In effect, Survival Mode—and therefore its human element—forms its investigative core. In comparison, Story Mode and its nonhuman element form the game’s emotional core. These investigative and emotional cores are crucial to Tokyo Jungle since the game cannot be explained in one mode alone. Players must explore Tokyo in Survival Mode to find USB archives, which are mandatory to unlocking more Story Mode chapters. Progressing in Story Mode lets players explore more of Tokyo Jungle with different animals, changing how they can explore the city. The information in the archives is also not arbitrary: information in Survival Mode elaborates on Story Mode in that USB data provides context on the events of the Story Mode chapter players just played. For example, one of the first archives players come across is the “Zookeeper Record,” which concludes by noting that the Zookeeper’s Pomeranian is agitated:

Zookeeper Record 1:

The zoo animals have been restless recently. The fierce predators are particularly on edge, and fights are often breaking out between them. Feeding time has become quite frightening.

I think I’ll talk to our vet about administering some tranquilizers…

Zookeeper Record 2:

We’ve adjusted their diet, but the condition of the animals has yet to change. Even our Pomeranian at home seems agitated and unable to sleep.

I wonder if all animals in the area are suffering similar symptoms.

Since the Pomeranian is the first animal the player controls, it behaves like a tutorial character and is thus meant to explain the game’s basic mechanics. During the Pomeranian’s story, it kills, breeds, and forms a family unit by necessity. However, when players then go to the Survival Mode to unlock the next story chapter, they find archives which reference the Pomeranian through the perspectives of its human owners. Here, the Pomeranian is not just a dog freed from human control, but a dog informed by humans around it. Its actions are seen as simultaneously natural (breeding, killing, eating) and unnatural (the sudden success of its natural habits made mysterious by the note commenting on its agitation—can a Pomeranian be that vicious?). Playing as the Pomeranian makes the player uncertain of the animals’ “natural” behaviour, as they are so entangled by both human influence and the game’s mysterious science fiction premise.

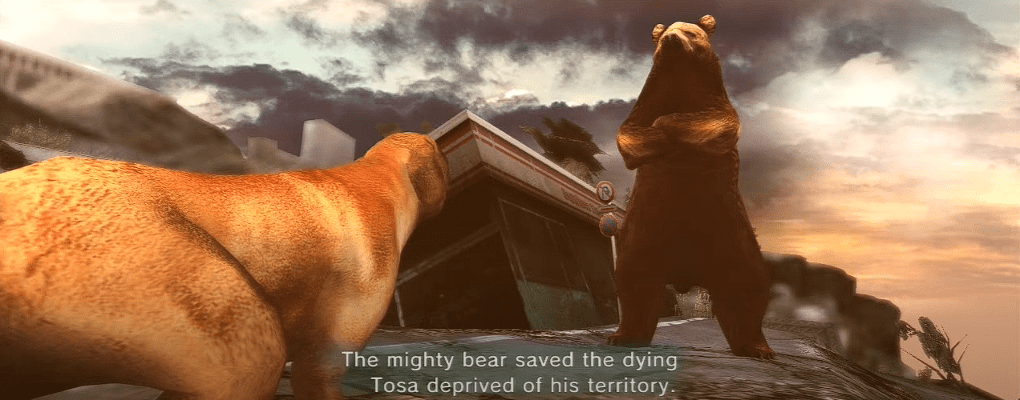

The connection intensifies as the Story Mode progresses and animal drama becomes more humanlike, reflecting the intelligibility of worlding. The game is aware that a critique of anthropocentrism cannot present a wholly new imagination but needs to negotiate pre-existing cues into new ones. The first notable transition happens in the multi-chapter dog war, an ongoing feud between clans of dog breeds, the Tosas and Beagles. The player controls both breeds and sees both vantage points: they initially play as the Beagles, who mount an offensive against the ruling Tosas. Afterwards, they play as the Tosas and must reclaim their dominion over Tokyo by destroying the Beagles. Notably, the Tosa storyline develops over the course of several chapters where the player needs to pilot the Tosa back to the position of, quite literally, top dog. At the Tosa leader’s nadir, when all his clan is scattered or killed, he comes across a bear who stands on its hind legs and who, instead of attacking him, offers an alliance. Should the Tosa kill the leader of three groups (crocodiles, tigers, and chimpanzees), the bear will give the Tosa the tools he needs to revive his clan.

To aid the Tosa in this mission, the bear gives him a pair of gloves with claws attached. This is one of the rare breaks in the game’s categorization of animal classes and their respective mechanical associations. Up until now, the game categorizes animals into attack groups: herbivores are stealth classes, dogs use lunge attacks, and cats use swipe attacks. The Tosa wearing clawed gloves is a way for the player to employ a more lethal moveset, especially as enemies become more difficult. At the same time, the dog’s use of what are ostensibly animal-made tools transforms the game’s depiction of the animals from naive inheritors of a humanless order to regenerators. They are not passively adapting to a post-human world, but in some ways becoming new humans themselves. However, they are not becoming humanlike because circumstance or environment has made them humans, but because human drama is how the game negotiates nonhuman subjectivity to human players.

The distinction between animals becoming humans versus presenting animal drama through anthropocentric narrative structures (as Tokyo Jungle is doing) is demonstrated by the fact that Tokyo Jungle’s story explicitly rejects the return of humans. Human-like qualities no longer remain the domain of humans but become presented as chthonic to nonhuman subjects. The apocalypse of Tokyo Jungle allows new means of imagining entanglement while simultaneously expressing methods in ways understandable to human players. Tokyo Jungle does not demonstrate a humanless apocalypse as an alien space, specifically because the animals are not others; they are interimplicated subjects who still bear the tracings of human intervention, but what makes new subjectivities possible is how old messages and narratives are repurposed through the lens of extant beings. Consider how the Tosa story unfurls: in the process of dramatizing what might have been natural animal territorial disputes, Tokyo Jungle leans heavily on human theatrics to dramatize its narrative. Up until this chapter, the game has wed its mechanics to relevant subject matter: the animals fought for territory specifically for survival, they survived despite the harsh new environment, and the desire to breed forms the fulcrum of the nascent animal clans. In other words, even anthropomorphized, chapters in Tokyo Jungle’s Story Mode are issues that can be reasonably understood to double as animal concerns. Chapter 10 builds upon a previous story of a Tosa who has its lost territory, setting up a revenge plot that takes a dramatically different route in that it focuses on honor, and as a result takes a sharp turn away from the struggle of animals to animals who are becoming human-like in their dramatic arcs. The Tosa’s relationship with Bear (who constantly presents themselves as the “Chief”) is not presented in any sense as animal-like. Instead, it adopts a mentor and student relationship.

The Tosa arc and the animals’ adoption of human characteristics demonstrates that despite a focus around worlding, we can still see how ideology shapes subjects, specifically through ideology in the Althusserian (1970) sense: a reproducing structure of social relations with regards to material modes of existence. In this context, an anthropocentric narrative undergirds the Tosa’s drama, that the apotheosis of the Tosa is presented (and rewarded) with the mawashi, an ornate silk garment used in sumo wrestling, itself a highly ritualized combat sport. The Tosa arc is where the game makes its most distinct transition from animal instincts to ritual. This attire marks him as a yokozuna, wrestler of the highest rank. The Tosa attains its rank not through a battle between enemies, but through a turf war enacted by a desire to reclaim its honor. The animals adopt very similar habits, not just because of repressive mechanisms, but because even consideration of interimplication can be seen as interpellative. Envisioning a new space means being able to express that order to subjects of an old one in an intelligible way. The Tosas must adopt the semiotics of sumo wrestlers to capture the sentiment the developers were aiming for, and they must use the claw tools in a way commensurate with the way the game’s narrative was set out. This human-like drama in Tokyo Jungle comes off as a form of ludic worlding, what Kathleen Stewart (2013) calls a composition of generative forces, a collision of interimplicated matter and matters (119). Simply put, Tokyo Jungle plays the worlded relation of its animal characters: players are not playing an animal (with X characteristics), but playing as animals affected by humans, both diegetically (domestication) and literally (as controlled by human players). Like the pigeons in Haraway’s recounting, animals in Tokyo Jungle are not animals, but animals after humans.

Tokyo Jungle as Anti-Apocalypse

The Tosa arc is also emblematic of another tension emerging out of a setting revolving around post-human apocalypticism: the anthropomorphizing of the nonhuman subject. Core to Crispy’s initial design document is the use of animals—especially domesticated and cute animals—juxtaposed with unfamiliar environments. In an initial pitch of the game, Kataoka (2013) relied on photoshopped images of animals in brutal engagements with each other using Nakano’s photographs. More specifically, in demonstrating the game’s attractive elements, he stressed the Pomeranian as the initial protagonist. The Pomeranian represented an animal that was seen in Tokyo as more of an accessory than a subject, a living being which largely existed in relation to another. Additionally, the value in the Pomeranian as the initial protagonist also allowed Crispy’s to levy its cuteness as a selling factor to get players engaged and excited by the game. At the core of Crispy’s pitch is what Hemmann (2018) notes is an affective appeal, utilising the cute aesthetics of many of the animals juxtaposed with their environment (91). It’s important to note that animals acting like humans are not unique to Tokyo Jungle. Hemmann makes a similar observation, noting that Japan’s cute culture interlocks with an ongoing practice of giving extremely humanlike behaviours to otherwise nonhuman entities (93). Media properties such as Pokémon, for instance, depict animals with human-like personalities and qualities (including the ability to parse and understand human languages).

What sets Tokyo Jungle apart is how it specifically uses these same cute strategies in its setting: the use of cute is how tension between animal and human subjectivities not only collide, but also commingle. Cute, in this sense, is always in tension between the human player (who sees these animals as cute) and the dangerous environments these cute animals find themselves in. We can see the logic play out in the Tosa arc: the anthropomorphizing of Bear (“Chief”) and the Tosa makes their engagement not only intelligible, but also “cute.” The anthropomorphizing of animals generates a crucial corollary which is played out by the game’s focus on animals: who isexperiencing the apocalypse? Throughout the game, the player’s affection for the animals is enabled mechanically; players play as domesticated animals who start off weak, but become stronger, and the game rewards players for it with congratulatory messages and snippets of storytelling. When the Pomeranian succeeds in finding a mate and starting a clan, the game doesn’t congratulate the player for surviving, but for their ascension into a patriarch of a clan. While the player might find the Pomeranian’s story cute and thus its arc endearing, they are effectively playing a violent battle for supremacy. The game leans on a core action gameplay progression system (kill enemies, achieve objectives, become stronger) to empower animal proxies, suggesting in the post-apocalyptic world of Tokyo Jungle, animals are not the ones experiencing post-apocalypse.

Tokyo Jungle’s depiction of animals in the environment not only stresses a tentacular vision of human-animal relations, but also demonstrates that the apocalypse is not a universalist engagement but a contextual one. More importantly, the perspective of apocalypse extends not just into questions of communities, demographics, or religions, but into deep axioms like ontologies. Tokyo Jungle presents these questions along similar lines, and it is unsurprising that its only plot choice revolves around this issue: the animals do not, and never have, seen the incident in the game as apocalyptic. The game never once speaks of the situation in Tokyo Jungle as apocalyptic. It often uses the idea of a “brave new order,” but rarely does the game speak of a fundamental revelatory shift in the same way we think of as apocalypse. In fact, we, as humans, see Tokyo Jungle as a post-apocalyptic game, but there are no humans in-game to situate that perspective.

At the same time, the game employs and depicts human-influenced spaces as challenges without solutions. Nowhere is this more visible than in garbage bags, which demonstrate how players engage as animals as interimplicated subjects through basic procedural engagements. This is accomplished through the game’s environmental hazard, toxicity. Toxicity is a value that, when players hit a threshold, begins to consume player health. Polluted water and weather increase the player’s toxicity. Players cannot reduce toxicity in an area; rather, they can only reduce the toxicity of their own animal characters. Players have several options to reduce pollution, such as consuming clean food (to reduce toxicity) or wearing gas masks to avoid ambient toxicity. However, players can also wear garbage bags, protecting them from food-related toxicity, but increases the ambient toxicity levels unless they take off the bag. The tension between human and animal subjectivity is reflected in the mechanics of the garbage bag: players weigh the long-term cost of the bag compared to the immediate cost of toxic food consumption. In other words, the game not only plays with a deferred sense of long-term engagement with pollution, but also reflects the animal relationship to the traces of human action, setting up a subject neither wholly human nor animal. Though small, the garbage bag mechanic reflects broader, more higher-level relations mapped out in the game.

Conclusion

This is not to suggest post-apocalyptic games solely seek to uphold the socioeconomic status quo, but rather that visions of post-apocalypse tend to situate specific subjects—namely, humans—and how they may survive in these new environments. Tokyo Jungle, in comparison, aims to focus on a different subject entirely, but also demonstrates a deep awareness of the correlationist warning, in that oftentimes access and connection are one and the same. Its solution is engaging with its subjects by presenting them as transitional objects in that they are not wholly animal nor human, but both. It does not just suggest some human element to its drama, but instead outwardly employs idiosyncratically human dramas, up to and including the trappings of human society, to present an uninterrupted vision of subjectivity in the post-Anthropocene.

Games can map out relations of experiences, even if the experience here, one of the post-Anthropocene, is purely spectral. In other words, the vision of humanity without humanity is something that is only discussed. In this case, the source system of the post-Anthropocene is always bracketed in relation to assumptions of the nonhuman. Tokyo Jungle makes very few conclusions on the nature of the posthuman subject but maps out the means in which humans and nonhumans relate to each other. The goal, I suggest, is not simply pedagogy or didacticism, but to navigate and express relations of subjectivity when one side has effectively been removed from the equation. In some ways, Tokyo Jungle is at home in the medium of the digital game more than any other media; a device made by us about animals who perhaps never needed us.

Author Biography/Biographies

Yaochong Joe Yang is a PhD Candidate from Trent University. His research concerns apocalypse and ideology in gaming, specifically on a structural level. His latest research concerns the deployment of game logics in noninteractive narratives.

References

Algee. (2012). Tokyo Jungle walkthrough: Act 10 – A fateful meeting [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHw1TncW5Zw

Allison, A. (2013). Precarious Japan. Duke University Press.

Althusser, L. (1970). “Lenin and philosophy” and other essays. Monthly Review Press 1971. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm

Backe, H.-J. (2017). Within the mainstream: An ecocritical framework for digital game history. Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature Culture and Environment, 8(2), 39-55. https://doi.org/10.37536/ECOZONA.2017.8.2.1362

Bogost, I. (2006). Unit operations: an approach to videogame criticism. MIT Press.

Chang, A. (2019). Playing nature: Ecology in video games. University of Minnesota Press.

Condis, M. (2020). Sorry, wrong apocalypse: Horizon Zero Dawn, Heaven’s Vault, and the ecocritical videogame. Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 20(3). https://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/condis

Crispy’s! (2012). Tokyo jungle. PlayStation 3: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Hemmann, K. (2018). The cute shall inherit the earth: Post-apocalyptic posthumanity in Tokyo Jungle. In A. Freedman & T. Slade (Eds.), Introducing Japanese Popular Culture. Routledge.

Kataoka, Y. (2013). Tokyo Jungle and Japan’s gaming potential [Video]. GDCVault. https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1018095/Tokyo-Jungle-and-Japan-s

Lloyd Perry, R. (2017). Ghosts of the tsunami: Death and life in Japan’s disaster zone. MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Main, D. (2021, March 10). Photos: A decade after disaster, wildlife abounds in Fukushima. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-abounds-in-fukushima-nuclear-exclusion-zone

Meillassoux, Q. (2008). After finitude: An essay on the necessity of contingency. Continuum.

Naughty Dog. (2013). The last of us. PlayStation 3: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Priyadharshini, E. (2021). Pedagogies for the post-Anthropocene: Lessons from apocalypse, revolution, & utopia. Springer Nature.

Quinby, L. (1994). Anti-apocalypse: exercises in genealogical criticism. University of Minnesota Press.

Reinhard, A. (2018). Archaeogaming: An introduction to archaeology in and of video games. Berghahn.

Sekine, Manabu. (2021, March 11). Genpatsujiko-kara jyuunen, Iitatemura no takumashii yasei. National Geographic Japan. https://natgeo.nikkeibp.co.jp/atcl/photo/stories/21/030300012/

Stewart, K. (2013). Tactile compositions. In Harvey, P., Casella, E. C., Evans, G., Knox, H., McLean, C., Silva, E. B., Thoburn, N., & Woodward, K. (Eds.), Objects and Materials (119-127). Routledge.

Tanaka, M. (2014). Trends of fiction in 2000s Japanese pop culture. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 14(2). https://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol14/iss2/tanaka.html

Thatgamecompany. (2009). Flower. Multi-Platform: Sony Computer Entertainment.

Thibault, M., Fernández Galeote, D., Macey, J., & Jylhä, H. (2022, September 5-8). Forests in digital games – An ecocritical framework. FDG ’22: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Athens, Greece. https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3555858.3555941

Tosa. (2015). Fandom. https://tokyojungle.fandom.com/wiki/Tosa