by Shaif Hemraj

Published August 2025

Download full pdf of article here.

Abstract

This article presents a practice-based game design study that explores the topic of development crunch and how it can impact creative expression in the games industry. Drawing on the creation of a practical prototype developed under tight time constraints specifically for this research, titled Game Maker Mayhem (GMM), I reflect on how simulated crunch conditions can influence creative decision-making and project outcomes. This project was designed to mimic the kinds of compromises developers often face during crunch, including diminished polish, reduced functionality, and constrained artistic scope. Rather than offering a traditional empirical analysis, this study uses reflective practice as its core methodology, which is an approach that emphasizes learning through iterative self-evaluation during the act of making (Schön). By doing this, I believe it will help with positioning the prototype as both a pedagogical tool and a critical commentary on unsustainable labor practices. The production of Game Maker Mayhem under simulated crunch conditions revealed how the pressure of a tight deadline led to the compromise of creative decisions, as well as other artistic constraints often reported in real-world crunch scenarios. Insights from this design process are further supported by existing academic literature (e.g., O’Donnell, 2014; Weststar, 2015) and industry case studies (e.g., Schreier, 2018; GDC, 2019) that contextualize the broader effects of crunch on game production. While this study does not attempt to generalize its findings across sectors in the industry, the development of Game Maker Mayhem contributes to ongoing conversations about labor ethics in creative development and demonstrates how design practice can offer valuable perspectives on complex production issues. Additionally, it also embodies a reflective, practice-based approach by using the lived experiences of the developers as a means of critique and inquiry. Furthermore, it works to engage with debates around the sustainability of crunch, as well as highlight the trade-offs involving creativity and time constraints.

Keywords: game development, crunch, labour practices, creative expression, production, management

Introduction

Challenges related to planning, time management, and labor practices have become increasingly visible across different sectors of the games industry, particularly in large-scale AAA production (Brogan, 2021). In fact, this practice is so frequent that there is a term for it: “crunch.” Crunch is defined as intense periods of development in which developers are expected to work extended hours under pressure to meet deadlines that are often seen as unreasonable (Cote & Harris, 2021). As Brendan Keogh (2023) argues in The Videogame Industry Doesn’t Exist, the diversity of labor models, studio sizes, and production practices resist easy generalization; while this is true, this article focuses on several common crunch-related pressures across different contexts. Game development crunch has been explored in existing research, with discussions made on the impact of labor practices, economic pressures, and the technical deficiencies that can occur due to rushed development. While many have shed light on the harmful effects of crunch—such as burnout, health issues and reduced job satisfaction (e.g., Weststar, 2015; O’Donnell, 2014; Weststar et al., 2019)—how crunch can directly impact and negate creative expression in games has been mentioned only briefly and remains underemphasized in existing research. Yet creative expression can be a critical component of game development that can often drive innovation, storytelling, and player engagement (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004). Creativity is also often limited by audience expectations that essentially hold game developers hostage, causing developers to compromise creative visions and limit the artistic potential (Barroso, 2020). High standards can require extensive working conditions to meet them, reinforcing a market where crunch can become normalized to stay competitive (Weststar & Legault, 2018).

In fact, some developers argue that without these intense periods of overtime, games can’t maintain the expected level of quality from audiences. Famous games director Niel Druckmann, for instance, notably argued that there is “no one solution” to crunch, and that it’s often seen as a necessary evil to polish AAA titles to the standards expected by players (Notis, 2021). Furthermore, Cote and Harris (2021) note that developers often perceive the additional work completed during crunch as a key contributing factor to notable game elements that helped the success of their products, such as the Zombies mode introduced in Call of Duty: World at War (Treyarch & n-Space, 2008). This highlights the complex reality of crunch, where some may view it as necessary, even at the cost of long-term sustainability and worker health. In order to better understand the developer perspective, this project does not pursue a traditional empirical study but instead adopts a practice-based research approach to explore how development crunch can influence creative expression; to that end, my collaborators and I created Game Maker Mayhem (GMM), a serious game prototype built under time constraints that simulate the pressures of rushed production cycles through written scenarios meant to recreate the thought process of what encourages crunch. Additionally, players are required to make rapid creative and production decisions under pressure, choosing to do so at the expense of profits or morale.

While the idea of developing games for a living may seem ‘fun,’ ‘rewarding,’ or ‘easy'(Banks, 2013; Nieborg, 2015), players or fans alike may not realize how incredibly challenging working in certain sectors of the games industry can be (Cote & Harris, 2023a). This is reflected in a survey conducted by the International Game Developers Association, which notes that as many as 40% of game developers are expected to work overtime, with little to no financial compensation (Weststar et al., 2019). It’s evident that the creation of a complex digital media product such as a game can often require extensive preparation and effort to ensure a high-quality result, which is why short deadlines can lead to potential disasters. In addition to products failing to meet quality standards because of rushed development, crunch can also force developers to compromise creativity to ensure a complete product sooner (Josefsson, 2017).

The causes of crunch, such as unrealistic audience expectations, tight deadlines, and economic pressures, have been well-documented, but the topic of how crunch culture also stifles creativity has received far less attention. On top of using a practice-based approach in the form of Game Maker Mayhem, this paper will shed additional light on this topic by analyzing developer interviews, existing literature, and examples of games that have been directly impacted because of crunch. Games with crunched cycles that I will be using as case studies include E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Atari, Inc., 1982), Cyberpunk 2077 (CD Projekt Red, 2020), and The Quiet Man (Human Head Studios, 2018). These games in particular were chosen as case studies because they each exemplify how working with crunch conditions can negatively impact creativity in development, as rushing content and limiting polish are notable factors that can lead to critical and commercial failure. By combining theoretical analysis with praxis (the creation of GMM), this paper ultimately aims to provide an in-depth and effective exploration of how crunch can impact both developers and the creative process. In addition, this research advocates for a far more sustainable system, compared to crunch, in the industry moving forward.

Literature Review

An Introduction to Development Crunch in the Game Industry

Game development crunch has become an unfortunate hallmark of the industry, with employees often expected to work between 60 to 100 hours per week to meet tight deadlines (McCarty, 2019), despite the severe toll it takes on their physical health, mental well-being, and personal lives (Schreier, 2018). In addition, while game workers may be required to work under strict deadlines, research suggests that the industry has other ways of taking advantage of people. For instance, passionate workers may willingly disadvantage themselves by working for free “in order to follow their dream of one day being paid to make video games” (Keogh, 2021). Cases like this have become so common that workers who accept this treatment are often referred to as “passionate play-slaves” of the video game industry (de Peuter & Dyer-Witheford, 2005). The issue of crunch often gains a wide amount of attention from players and popular press outlets when players experience the downsides to crunch culture—such as when a game launches with significant bugs or performance issues. Game players can be quite divergent on this issue, with some claiming that it’s necessary practice to ensure products can meet their standards, while others argue that changes can be made to improve working conditions (Cote & Harris, 2023a). This is not just true of gamers, though; industry standards and mixed consumer expectations extends to other media in the entertainment industry, such as film, television, and music, where workers are expected to endure unreasonably long hours, unfair pay, and rough employment conditions because they should be passionate about their work, which employers exploit (Hesmondhalgh & Baker, 2011). For games, players can sometimes be quick to praise them when they enjoy them, even if a game was developed through means that can lead to unfair treatment of those who developed it, such as unpaid overtime and burnout.

When players are in fact vocal about the impacts of rushed development and sub-par products, this backlash can potentially pressure companies to make changes that can allow for better quality control and working conditions to appease fans, like a strike (Siuda et al., 2023). For example, many games developed by Electronic Arts (EA) are very notable for having rushed development cycles that lead to rough working periods, such as Mass Effect: Andromeda (BioWare, 2017) and Anthem (BioWare, 2019). While multiple factors—including engine challenges and management turnover—contributed to these troubled launches, reports from developers and investigative journalists suggest that rushed timelines and sustained crunch were key drivers in limiting both quality and creative execution. Jason Schreier, a veteran investigative journalist formerly at Kotaku and now with Bloomberg, is particularly well known for his in-depth reporting on the video game industry’s labor practices. Notably, he highlights how Anthem’s development was rife with internal dysfunction, shifting leadership, and a lack of clear direction which forced developers into prolonged periods of crunch, ultimately undermining the game’s vision (2019). Similarly, Patrick Klepek, a senior reporter at Waypoint (Vice’s gaming vertical) reported on Mass Effect: Andromeda‘s troubled production, arguing that it was hindered by an over-reliance on the Frostbite engine, poor planning, and late-stage cuts (2017). These conditions reflect larger systemic problems in the studio’s development culture, which have also been echoed in other critiques, such as the “EA Spouse” letter by Erin Hoffman (2004), which famously exposed the personal and mental toll of excessive overtime at Electronic Arts. This also helps explain why EA has frequently been criticized for its labor practices (Thier, 2012; O’Donnell, 2014). EA is not the only culprit, however. An investigative report by games news outlet Polygon has notably highlighted that this issue is common amongst many games studios, such as Rockstar Games, Naughty Dog, CD Projekt Red, and BioWare (Carpenter, 2021). The topic of unethical working conditions in the larger tech industry, including game development, has slowly become a more widely discussed topic, even being covered in television shows such as Silicon Valley (2014) and Mythic Quest (2020). This increase in public awareness—alongside workers and consumers questioning the downsides of crunch—is significant, as it puts pressure on the industry to re-evaluate whether profit and deadlines can continue to outweigh sustainability, creativity, and human dignity in game development.

How Companies Navigate Through Development Cycles

Crunch is often justified by companies as a way to release (unfinished) games early and meet a time-based window of opportunity that can be more profitable than releasing finished games at another point in the year. There are various examples of rushed games that were reviewed negatively by critics but still managed to sell more units than those that waited until the game was complete to launch; companies often believe that this difference is due to the timing of release, which unfinished, crunched games can release around. Several factors affect the success of crunch, such as whether the platform for release has a wide user base, the timing of the game’s release in relation to holiday periods, and the overall popularity of the franchise. For instance, Pokémon: Scarlet (Game Freak, 2022A) and Violet (Game Freak, 2022B) sold over double the number of units than Pokémon: Ultra Sun (Game Freak, 2017B) and Moon (Game Freak, 2017A), according to Nintendo’s financial sales data (2023). Ironically, this happened even though Pokémon: Scarlet/Violet was reviewed very negatively due to how they were released in an unfinished and rushed state. They were also criticized for performance issues, lack of new features, ugly visuals, and hilarious/tragic bugs because of its rushed release (Tassi, 2022). It’s worth noting, however, that Nintendo Switch has a larger number of users, which likely played a role in the game’s success, as other Pokémon games for the platform have achieved similar sales (Nintendo, 2023). This example shows that while rushing a game may harm its quality and reviews, strong brand loyalty, platform popularity, and well-timed releases can still drive high sales—highlighting a tension between commercial success and product quality.

In some studios, especially those operating under tight market pressures, accelerated development cycles are often used to increase release frequency and short-term profitability, sometimes at the expense of worker wellbeing (Peticca‐Harris et al., 2015). Sadly, companies may opt for conventional and simple ideas to expedite production. This can result in games that lack effort or fail to distinguish themselves, which can then stifle innovation and encourage poor practices. While profit may be one of the core reasons as to why rushed development can be frequent in the games industry, another notable source is poor planning and inadequate management (Politowski et al., 2021). Heather and Ryan Chandler, authors of Fundamentals of Game Development, define pre-production as the critical planning process in the first stage of a project, often spanning between “10 to 25 percent of the total development time of a game” (2010, p. 99). This phase can be essential to ensuring a smooth production process; when there is a lack of effort put into this area, crunch becomes more likely. Realistic budgets, timelines, and resource allocations are central to avoiding crunch later in development, because additional work can be needed to compensate. These common issues are described by Peticca-Harris et al. (2015) as the three parts of the ‘iron triangle’ in project management (scope, cost, and time) are clear causes of crunch across the larger tech industry. In an interview, Casper Field, an ex-studio head at Wish Studios, also argues that common problems in game development often occur due to “poor planning by (often inexperienced) managers; under-staffing of the team; over-specification of the product; and refusal or inability of middle management to push back on demands from above or outside” (Dring, 2018). This demonstrates how crunch is not just about profit—it’s also a result of internal mismanagement.

While many products in the industry have a rushed development cycle, some games successfully avoid issues. For example, the development team behind Hades (Supergiant Games, 2020) has made a strong effort to ensure employees work in reasonable conditions by supporting an environment where breaks are encouraged, with policies that go as far as to ensure that workers all take at least 20 vacation days minimum (Nesterenko, 2020). As a result, developers were able to work until the project was completely ready, ensuring that the game could reach its full potential. This example serves as a rare but important counterpoint to the culture of crunch. While Hades is often praised for its innovation and polish, its success should be understood in context: as a self-published indie game with creative autonomy, it operates under different constraints and freedoms than large-scale AAA productions. Some lower-budget titles may achieve impressive profitability relative to their cost, particularly when creative design, timing, and audience engagement align. This highlights the importance of creativity and thoughtful design over production scale, particularly relevant in the context of development crunch, which is often justified by the belief that it leads to better products. This matters because crunches are often justified by the idea that longer hours and bigger teams make better games, but sometimes smaller, more creative projects succeed and exceed the popularity of triple AAA games by simply being more innovative and efficient. For instance, Minecraft was notably made by a solo developer by the name of Markus Persson with a small initial budget and has since sold over 300 million copies worldwide (Richard, 2023).

However, this should not be taken to suggest that lower budgets inherently produce better results, or that creativity alone guarantees success. The commercial landscape for games is shaped by many variables—including platform saturation, marketing budgets, and player expectations—which differ widely between indie and AAA development models. For example, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (Rockstar North, 2002) sold 17.5 million copies (Bowen, 2023) despite a $5 million budget (Kushner, 2012). Adjusted for inflation, this would be about $9 million in 2025—still far below the $50–200 million budgets of modern AAA games (Competition and Markets Authority, 2023). In contrast, Mass Effect: Andromeda had a $100 million budget but sold only 5 million copies (Kent, 2017). Assuming an average retail price of $60 per game, this means Mass Effect: Andromeda may not have been profitable as it was expected to be, especially when factoring other areas such as marketing and ongoing costs. Vice City was also far better received on review sites like Metacritic and IGN, while Andromeda was heavily criticized for bugs and lack of polish—clear signs of a rushed development. While these games emerged in very different eras with distinct technological, economic, and consumer contexts, this comparison is illustrative of how higher production budgets and longer dev cycles do not guarantee success—particularly when poor planning or crunch disrupt development workflows.

Understanding Creative Expression in Games Development

Video games can be far more than just interactive and entertaining pieces of software; they are powerful forms of expression and language (De Lucena and da Mota, 2017). Games can express themselves creatively using a variety of methods, such as through storytelling, visual design, artistic messages and even sound design. In fact, there is a term for games that are produced for the sole purpose of creative expression rather than entertainment— “art games” (Parker, 2012). Renowned art games such as Limbo (Playdead, 2010) and Gris (Nomada Studio, 2018) are notable examples that demonstrate the potential of creative expression in games, as both are acclaimed for their capacity to elicit thought-provoking experiences among players through a combination of symbolism and visual elements (Rodrigues et al., 2022).

The medium of games allows artists and developers who wish to provide a unique avenue for creative expression to do so through direct interactivity, something that isn’t often possible in other mediums such as television and film. Unlike a video or painting, in which audiences can simply look at the art, games allow for agency. This can add layers of complexity to storytelling and allow individuals to play a role in how the overall experience is shaped. However, direct input can be both a weakness and a strength, as interactive elements in software can lead to unintended outcomes when players use it in ways not intended by the creators.

The process of developing games with rough working conditions can encourage the cutting corners and ignoring necessary quality assurance, which in turn leads to bugs and glitches. It’s for this reason that crunch can undermine the creative goals and artistic integrity of projects, particularly when artistic vision must be sacrificed due to rushed deadlines or unexpected compromises (Archontakis, 2019). The process of taking creative ideas and expressing them through the medium of games can require a delicate balance between artistic vision and technical restraints, as compromises in game development can lead to potential disasters when elements must be removed due to unexpected plans or rushed deadlines. Effective pre-production are especially relevant when making art games, as they often rely on critical acclaim and involve expressing a message through artistic and creative means. While some games may not be affected by vocal criticism as a result of crunch, games with this focus on creativity (be it art or narrative) may be additionally undermined by crunch practices because fine-tuning of creativity is difficult to achieve when rushing. Notable indie developer and programmer at Innersloth, Adriel Wallick, has spoken out on this issue, arguing that excessive work hours and constant pressure can stifle creativity as well as diminish overall game quality (2016). Reflecting on her own experience, she publicly reflected that “the lifestyle I was leading—working all the time—wasn’t sustainable or healthy, and it was actually hurting my creativity” (Wallick, 2016).

Successful Games Amidst Time Constraints

Not every game with a rushed development cycle leads to failure. A notable example comes from The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask (Nintendo EAD, 2000), which had a development period of less than two years, according to a 2015 interview conducted by the late Nintendo President and CEO, Satoru Iwata. Iwata clarified that completing the game on time was a task that was only achievable by reusing assets from The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo EAD, 1998). Shigeru Miyamoto, then Senior Managing Director and head of Nintendo’s Entertainment Analysis & Development Division, reflected on the development challenges, stating, “A lot of people ended up working overtime due to the sheer volume of work that had to be done… As long as it was finished, anything was acceptable” (Nintendo Dream (2000) as cited in Nightingale, 2023). His direct acknowledgement makes it clear that Majora’s Mask was indeed developed under conditions of crunch, challenging the assumption that asset reuse from Ocarina of Time necessarily reduced strain on developers. In fact, Zelda director Eiji Aonuma himself acknowledged that he had to pull at least one all-nighter and didn’t even get to play the game from start to finish before release (Stalberg, 2023).

It’s worth noting that the final product was a critical and commercial success, as it sold over 6 million copies across all platforms worldwide (Radić, 2020) and averaged high review scores above 90 on popular websites such as Metacritic and IGN. However, Miyamoto’s reflection underscores the toll that accelerated timelines, and high expectations can place on development teams. For these reasons, development practices for Zelda games at Nintendo have evolved, with future titles in the series receiving significantly longer development periods. Notably, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (Nintendo EAD, 2017) underwent a development cycle of approximately five years, reflecting a shift toward more expansive and polished production process (Shea, 2022). Additionally, it’s worth noting that this game went on to be the best selling in the series, if not one of the best-selling videogames of all time with 34.51 million copies sold as of March 2025 (Nintendo, 2025). The sequel, The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (Nintendo EAD, 2023) took roughly 6 years to make, and achieved similar success and critical acclaim (Nintendo, 2023; Metacritic, 2023).

Another reason as to why developers may be encouraged to rush is due to “perpetual update culture” (Mertens, 2022), in which they can simply just make fixes after release, because of how games can allow for automatic patches and updates to resolve complaints and issues. This is especially relevant for the cases of games that may be considered unsuccessful on release due to poor performance and unfinished elements, only to be more successful later due to updates. Cyberpunk 2077 and No Man’s Sky (Hello Games, 2016) are particularly notable examples of this, as both games experienced rough launches prior to their significant changes through continuous updates, allowing for more positive feedback amongst the player bases later on (Siuda et al., 2023). In addition, the gaming industry has since evolved to the point where addressing issues is far less of a challenge and can even be done with direct assistance from the consumers, who can now essentially work as voluntary testers through forums and customer support requests (Mertens, 2022). In a way, this can help developers find issues in their games faster, although doing so may demonstrate a lack of effort in quality assurance.

Normalization of rushed development in this regard may have also had an adverse effect, encouraging customers to avoid buying products until later down the line. By waiting, consumers may have a more refined and polished experience when playing for the first time because of various updates and changes made after release. In some parts of the industry, particularly where marketing timelines dominate, releasing games before they are fully polished has become increasingly normalized (Tomlinson & Anderson-Coto, 2020). In fact, According to Ben Gilbert (2019) of Business Insider, Fortnite (2017) and Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) were developed under the conditions of 70–100-hour work weeks. However, these cases do not suggest that rushed development and crunch are good practices. On the contrary, such models are harmful and unsustainable, and the industry should strive to find healthier, more sustainable ways to achieve success.

Case studies

When developing Game Maker Mayhem (GMM), my goal was to simulate the challenges of managing a game development project under difficult working conditions. I also aimed to learn from past failures to avoid common pitfalls like overambition and poor organization. To do this, I studied real-world examples of troubled development cycles, specifically E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (E.T.), The Quiet Man, and Cyberpunk 2077. These games in particular were chosen due to their shared history of rushed development and compromises. E.T. and Cyberpunk 2077 have been cited as cases where rushed timelines contributed to incomplete releases, while The Quiet Man has been criticized for lacking polish and narrative clarity, which may reflect compromised creative execution. These cases highlight the complex decisions developers and managers face under pressure and show how tight deadlines can compromise essential features and ideas. Game Maker Mayhem is a metagame about crunch; it emphasizes making tough choices and finding a balance between hitting deadlines and supporting a creative vision. Players must manage factors like morale, progress, budget, and audience support, all of which are impacted by their decisions. By incorporating these case studies, the game presents realistic scenarios that demonstrate the consequences of poor planning and resource management.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial: A Case Study in Rushed Development

Development crunch in the gaming industry is not a new practice. For instance, some games that were built and released under rushed pretenses go as far back as the era of the Atari 2600, with E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and its five-week development cycle being a notable example. Its unfortunate release in such a rushed, low-quality state led to it becoming a financial failure for Atari (Linton, 2022) as its poor reception also led to many copies being returned, causing excess inventory that resulted in millions of copies being discarded (Ruffino, 2016). In essence, the game faced significant artistic compromises, as the immense pressure to develop it quickly meant that this game lacked interesting features, on top of not functioning as reliably as intended. Providing this game had a longer development period, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial could have been an engaging experience that aligned more closely with the creative ideas of the film. By rushing the production process, the product itself lacked the depth and creativity expected from such a major cinematic adaptation. As a result, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial stands as a notable example that demonstrates how creative media can be compromised when unreasonable deadlines are set in place.

It’s worth noting that the sole developer who produced the game, Howard Scott Warshaw, also resigned from working in the gaming industry due to his experiences and has since transitioned to being an officially licensed psychotherapist. His story highlights how the effects of crunch and burnout can cause long-term consequences that can lead to the loss of valuable talent and institutional knowledge in such fields.

E. T. the Extra-Terrestrial was also a contributor to the North American video game crisis of 1983 (Bogost, 2011), in which market saturation and poor-quality game releases led to a recession and the bankruptcy of multiple game companies. According to Ernkvist (2008), a combination of overproduction, mismanagement, competitive pricing, negative PR for Atari, and the pressure of adapting to frequent changes are attributed to causing the crash. As companies could charge the same prices despite the quality of the product, some were encouraged to release games as frequently as possible, ruining consumers’ confidence due to products becoming rushed, underdeveloped, and outdated quickly (Gallager & Park, 2002). According to notable Activision and Atari game developer David Crane (2016), prices of lower-quality games were reduced due to a lack of demand to compete with more reputable development teams that charged a higher price for better-quality games. As a result, quality titles were often ignored in favor of low-quality titles that drew sales away because of poorly informed customers. This case illustrates the major consequences that rushing the development of a game can have, affecting the product itself, as well as the individual creators, finances and reputations of popular game companies.

Navigating the Fallout: Lessons Learned from Cyberpunk 2077

The success of many games that were developed under strict schedules is a reason as to why crunch time is still so common today. One of the most notorious and controversial cases of a game with rushed development was Cyberpunk 2077 because the game was released in a very unfinished state. For example, Tassi (2023) argues that the holidays played a role, as selling games near Christmas could allow for more sales due to a potentially higher demand from consumers. As a result of the game’s rushed release, it was widely scrutinized by players on social media and players left negative reviews across various gaming platforms including Steam in a coordinated effort to demonstrate their dissatisfaction (Siuda et al., 2023, p. 653). The game’s failure to meet standards caused Sony to remove it from the PlayStation store for a period, while Microsoft decided to give users who purchased it digital refunds as a form of compensation. Another outcome of the fallout from Cyberpunk 2077 was how its overwhelmingly negative response caused the studio behind the game, CD Projekt RED, to decline in valuation by 75% (Francis, 2022). As a result of the controversies, the company eventually did create an apology video—titled “Cyberpunk 2077 — Our Commitment to Quality” (Cyberpunk 2077, 2021)—in which they expressed to consumers how they failed to meet expectations and how they would make up for it, promising to make internal changes as well. Despite the overwhelming critique, the game still managed to sell over 13 million copies on its release day, according to a financial report by CD Projekt Red (2021).

Despite the game’s initial profits, Cyberpunk 2077 still suffered from negative effects of crunch, like compromised artistic vision, unfinished mechanics, and technical issues. A strong public outcry, which was an extreme reaction to delays, contributed to the pressure to rush production (Thier, 2020). After release, CD Projekt Red did express a commitment to improving internal development processes, as well as addressing the issues in the game to regain customer trust (Nowicki, 2021), because of the flood of negative reviews. While public sentiment can create reason for crunch, public opinion can also prevent or address the negative effects of crunch. Some reviews for Cyberpunk 2077 have since been updated with more positive comments and scores to reflect the overall improvements; particularly notable are IGN and Metacritic’s revised reviews which highlight the many enhancements made to gameplay mechanics, enemy artificial intelligence, and performance optimizations to ensure the game runs at a far more reliable framerate (Marks, 2024; Metacritic, 2023). These updates have also made it easier for people to appreciate what was done right, such as how the game did creatively express a dystopian vision of the future, blending creative new ideas and urban aesthetics to craft a compelling story (Sun & Zhou, 2022, p. 643).

The Quiet Man: An Underdeveloped Creative Idea

While Cyberpunk 2077 salvaged its creative vision after release, not all games created under crunch can. A notable example comes from The Quiet Man, an action-adventure video game published by Square Enix. This game was unique in that it featured a deaf protagonist and incorporated gameplay elements and cutscenes from the perspective of someone with that condition, allowing for a very different experience from the default player in games. The game aligns very closely with what game scholars refer to as an “empathy game”, where a focus is placed on fostering understanding and emotional connection through gameplay (Ruberg, 2020).

Unfortunately, The Quiet Man was a commercial failure, as it was critically panned by a wide variety of journalists and reviewers to the extent that it was ranked as Metacritic’s lowest scoring game of 2018 with an average score of 29/100 (Henry, 2019). The lack of audio and poor writing throughout the game’s story made it unnecessarily confusing, inadvertently portraying deaf people as incapable of understanding the world around them (Sterling, 2018). The idea of intentionally diminished audio for gameplay can be viable and interesting if done correctly. For example, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 (Insomniac Games, 2023) implemented a similar strategy during the sections when playing as Hailey (a hearing-impaired character) in side-missions, which was well-received (Kennedy, 2023). According to Gordon (2018), The Quiet Man starts with an artistic premise that demands an amount of creative ingenuity, which is then unfortunately undermined by frequent glitches, repetitive gameplay, and a disjointed narrative experience. As a result, its gameplay came off as underdeveloped in comparison to other Square Enix games, such as Kingdom Hearts II (Square Enix Product & Development Division 1, 2005) and Final Fantasy VII Remake (Square Enix Business & Division 1, 2020). The game had a unique concept that audiences could have found interesting, but like Cyberpunk 2077, this was overshadowed by a lack of required effort placed in other essential areas; unlike Cyberpunk 2077, The Quiet Man did not recover after release. This game is a stark reminder as to why a lack of quality assurance and polish to get a product out to market sooner can often lead to its failure as well as undermine its artistic and creative elements.

Methodology

This project not only reflects on the creation of Game Maker Mayhem as a case study but also serves as practice-based research on the development process. Through its mechanics, narrative, and decision-making systems, the game also showcases how crunch impacts creativity and project outcomes. During all three stages of production, I worked with three other group members who were fellow classmates with me at the time: Sipeng Wang, Jialiang Xu, and Pang Yunhao. Sipeng was the character artist, background designer, and playtesting/QA lead for the project but also assisted in other areas such as designing artistic components for the backgrounds as well as games testing and quality assurance. Jialiang helped design icons for the user-interface elements and played a role in writing various scenes and scenarios for the story throughout the game’s development. Pang demonstrated his expertise in audio design by producing sound effects for the game, primarily the reaction sound effects for the characters. To align with the project’s thematic focus, our team of four members including myself had to work with a tight, three-month deadline as this project was for a group assessment, which tied in well as a design constraint. While Game Maker Mayhem reflects our team’s own development process and is not generalizable across the industry at a AAA or indie scale, the project offers experiential insight into the kinds of creative compromises developers may encounter under similar constraints. Our intention with this game is not to prove a universal relationship between crunch and creativity, but to offer situated, experiential insight that can inform broader conversations about development practices.

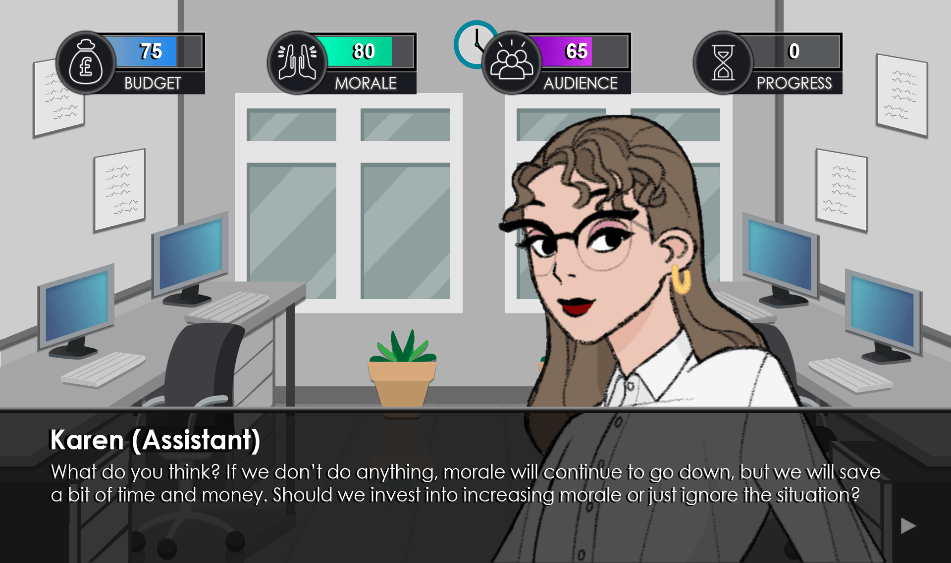

Reflective design methods can uncover tacit insights into decision-making, trade-offs, and emergent constraints within creative production. As Skains (2018) and Candy (2006) argue, creative artefacts can serve as both research output and analytic tool—offering a deeper understanding of the lived processes behind complex design problems like development crunch. We planned out GMM with this in mind, and used a system that places an emphasis on decision making with four key variables—employee morale, budget, audience interest, and project progress—each rated on a 1–100 scale. These variables are interconnected with poor performance in one area (such as morale) potentially causing setbacks in others (like progress). The game is designed to show how cutting corners to meet deadlines can undermine creativity and long-term success. By making these trade-offs visible, the project aims to raise consumer awareness of what goes on behind the scenes. This awareness is crucial, as it can shift player expectations and foster a culture that values sustainable and ethical development practices over rushed releases.

Introduction and Pre-Production

This section outlines the methodological approach taken in the development of Game Maker Mayhem, framed through the lens of practice-based research. Skains (2018) defines practice-based research as a process where the “creative artefact is the basis of the contribution to knowledge” (p. 1). This project follows such methodology, by discussing the overall production process as portrayed in the gaming industry through a reflective design analysis based on our own development experience. To ensure our practical prototype could be developed within a reasonable timeframe while also retaining our key ideas, general functionality and the intended visual quality, our team went through an extensive pre-production process so that we could remain on track and work without exerting ourselves. We used what we learned from studying existing companies and their failures to avoid making the same mistakes, such as spending too much time on planning, as well as organizing our work with functional and non-functional requirements to ensure we stay focused on the essentials. We also made a strong commitment to ensuring we would stay organized throughout the course of this project’s overall development cycle through frequent meetings, shared documentation and group chat discussions, as we were aware that crunch can be a result of poor project management. Dedicating time beforehand to determine essential factors proved to be effective, as we were able to ensure an efficient process that also gave us time to add additional polish, making the game look far more professional than we had initially expected. Asking potential questions such as how long our game should be, as well as how we could simplify the development process to avoid wasting our effort, proved to be an effective strategy that helped us prevent issues.

| Phase | Dates | Key Activities |

| Planning & Prep | Oct 28–31, 2021 | • Topic selection • Proposal and action plan • Research & brainstorming |

| Proposal & Early Production | Nov 1–30, 2021 | • Draft proposal & initial research • Teacher feedback & revisions • Storyboard/outline & citation logging |

| Production & Research | Dec 1–30, 2021 | • Finalize research questions • Record audio / collect visuals • Refine storyboard • Begin editing |

| Post-Production & Writing | Jan 1–13, 2022 | • Final fixing & effects • Match narration with visuals • Add citations • Peer review & written reflection |

| Main Category | Description |

| Strategies for Obtaining Information | This research approach includes learning from industry insiders through books, academic papers, and video conferences. It also involves studying pre-production strategies by watching interviews and professional discussions, which provide real-world insights into the planning processes of game design. |

| Researching Pre-Production | Research focuses on behind-the-scenes examinations of how popular digital media products manage their planning stages. It includes comparing how different companies handle pre-production tasks, offering valuable benchmarks and methods for structuring creative workflows effectively. |

| Viewing Popular Titles Among the Genre | This involves analyzing notable titles such as Doki Doki Literature Club (2017), Reigns (2016), Silicon Valley (2014), and Mythic Quest (2020). These examples help explore how genre conventions are applied and sometimes subverted, and they also provide inspiration from both gaming and non-gaming media. |

| Data Analysis Methods | The project uses both qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative methods include watching interviews and learning pre-production strategies from developers. Quantitative analysis involves comparing sales data across the genre and measuring development versus pre-production stage durations. |

Production and Post-production

Throughout the production of this prototype, I primarily worked in programming and asset creation while assisting in other aspects of the development process, such as planning, writing, optimization, and testing with the rest of my group. We had frequent meetings to track progress as well as discuss who would do what and when, although I learned after the fact that this process could have been far more efficient if we had used tools such as Trello to track progression. For this project, I used Clickteam Fusion and its visual event-editing features as I was already familiar with the engine at the time of the game’s production. Thanks to this decision, I was able to create the necessary mechanics involved in the visual novel genre without too much difficulty. As I was also dependent on team members to make the character assets, I also used temporary placeholder art I found online before replacing them with our official artwork. After I had completed the programming process, I then focused on making both environmental art and user-interface designs with my team members, both of which were done with Adobe Photoshop. We first had to research online to find references that would inspire us before settling on a perspective, art-style, and color scheme. After this process, we decided on sticking with a simple visual style, which emphasized a mostly grey and white color scheme. This artistic decision was made as we felt that these were the colors people would often associate most with offices and equipment. This also helped make the user-interface style and in-game environmental assets look consistent throughout gameplay. It was important that certain elements stuck out, such as the counter bars, which introduced different colors to make a contrasting effect. Once we finished production, we all collaborated to test the issues.

Practical Review

Our game illustrates how the management processes behind game development can encourage behavior that compromises creative expression in favor of delivering titles quickly for reliable profit. This became evident during our own development process, when some of my creative story ideas had to be cut to meet the self-imposed deadline—for example, pre-written storylines involving workers protesting and developers reacting to harsh player feedback. Working within a compressed timeline also led to decision fatigue, which in turn caused us to prioritize functionality and core mechanics over more experimental or expressive design elements. For instance, many of us had wanted to spend more time on improving the visuals, adding additional polish and writing more scenarios, a lot of our focus had to be spent on fixing bugs and assuring everything was both functional and reliable. These trade-offs reflected a core tension in development under pressure: while tight deadlines can increase focus, they often constrain creative scope and reduce opportunities for innovation. I was still particularly surprised with how fast and effective we all were when it came to the planning progress and overall pre-production stage, as we were able to come up with interesting ideas very quickly. I would argue that we did get a little ambitious here, as we were determined to push ourselves by making multiple scenarios for the protagonist to solve, when we most likely could have made the same points with less.

There were times when our team had to discuss and commit to scrapping some non-essential elements to ensure the deadline we set could be met, such as my plan to have additional background images for offices representing different professions, including HR, programming, and art. Production of the game went smoothly for the most part, as the concept was simple. My method of programming for the project, however, was inefficient because I rushed, and I could have optimized the game further providing we had more development time. Due to insufficient research into efficient programming strategies, I made the mistake of opting to hardcode a lot of necessary text into Clickteam’s event editor, as opposed to taking the time to learn how to store it externally, which would have been far more ideal from a scalability and maintainability standpoint. This experience reinforced how important research during the pre-production stage can be, as well as why many rushed games may not run as smoothly as intended, as although the game works, it could have worked better.

Our post-production stage was mostly dedicated to bug fixing as opposed to polishing, but we managed to solve any problems we encountered through a meticulous testing process in which we would all test the game frequently and take notes. I am pleased with the result of the prototype, as I believe that our group successfully managed to produce a game that achieved the goals that we had initially set out to complete. Game Maker Mayhem accurately depicts the kinds of decisions and behaviors often exhibited by management as well as the variety of issues that often occur in the industry, such as strict deadlines, poor communication, and a lack of care for employees. For instance, we used our game to discuss the topic of how it’s common for the preferences of workers to be ignored in favor of focusing on making a larger profit, as well as how management may manipulate passionate workers to their advantage (see Figure 8). These topics were inspired by real scenarios from existing games and development situations, such as the troubled production of BioWare’s Anthem, which suffered from a rushed and disorganized pre-production phase, and Cyberpunk 2077, where passionate developers were pushed into extensive crunch under management pressure to meet commercial deadlines. Players can learn from this game, and it can work to raise awareness of the harsh working conditions often present in game development.

Upon completion of the first section of the game, our group asked a lecturer in the field of game development to try the experiment for themselves and see how they would navigate through the scenarios we provided. We were excited to see that they found the game straightforward and easy to understand. Interestingly, we observed a nuanced decision-making process: in some situations, they chose to play it safe, prioritizing cautious strategies, while in others, they took more significant risks, demonstrating a thoughtful balance between risk and reward that reflected real-world managerial dilemmas. Although we did not conduct a more extensive or formal playtesting phase beyond this point, the development process itself offered valuable insight into how decision-making pressures can influence managerial strategies and lead to creative compromises. Real-world examples reveal how the games industry can sometimes be exploitative, which we incorporated into our game’s narrative. We drew inspiration from reports about companies like Electronic Arts, where employees have described prolonged work hours and poor work-life balance, leading to significant mental health challenges (Gilbert, 2019). One notable instance of how we incorporated a scenario like this in our game was when we came up with a dialogue where the player was given the choice to not remind workers to take breaks, mirroring the common issue of how some employees can forget to use their PTO hours. In other instances, we tried to emphasize the mindset keeping narrative and aesthetic choices safe and simple to avoid extending the budget and audience criticism, as shown in Figure 8.

As discussed earlier, Game Maker Mayhem was rushed in various areas to meet the deadline, limiting its potential. Providing this project was revisited, I believe it could be improved, as well as expanded on. For instance, it could also be adapted as a pedagogical tool in game design courses, helping students and aspiring developers explore how production decisions, time pressure, and management trade-offs affect team morale, project quality, and creative expression. Additional elements could be added to the experience to enhance learning, such as a requirement to integrate reflection and feedback, as well as potentially having students experiment with scheduling, team roles, communication challenges, and shifting priorities. Teamwork is an essential part of games development and helping students understand the importance of how to effectively work with others can make for a powerful learning experience. Reinforcing critical thinking and iterative learning through having learners analyze their decision-making processes and evaluate the outcomes of their choices could also prove to be very useful, as it could promote self-improvement. The issue of exploitation of interns is also one that could be worth addressing, especially as a method of guiding those with no or little work experience. Research shows that in some cases, young developers are subjected to little, or no pay paired with intense working conditions, often with the promise of a future full-time position that never materializes (MacDonald, 2021).

Conclusion

Central to our inquiry around the ethics of crunch was a practice-led approach, where knowledge was generated through the process of making a playable prototype, Game Maker Mayhem. Rather than focusing solely on player reception or gameplay analysis, the act of designing and developing the game itself served as a form of critical reflection. Through this hands-on creation process, I examined how systems and mechanics can embody and critique exploitative labor models, including crunch and predatory monetization. The project demonstrates how game development can function as a mode of research, using creative practice to interrogate and respond to the ethical and artistic challenges facing the industry today. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this approach, as Game Maker Mayhem is a game produced by a team of four that didn’t use financial resources for its production. Instead of reflecting studio or industry standards, our contribution lies in demonstrating, through practice, how labor constraints can influence design outcomes. That being said, it came as no surprise that the rushed development of our project essentially stifled our overall potential, just as how crunch in the games industry can stifle innovation, downplay creative or artistic messages expressed through the medium of games and lead to lower-quality products that fail to meet their full potential. Despite this, we feel that along with providing insight in the form of a practical component, the overall game works as an educational experience, making it a valuable tool that can highlight the challenges that come with managing the process of developing a game.

While crunch is a persistent issue in many sectors of the gaming industry, particularly in AAA studios, crunch is often meaningfully remediated when consumers vocalize their concerns. For instance, calling out the ethical issues, protesting by refusing to purchase or even contributing to the conversation about it has proven to be an effective tactic that can sometimes pressure companies to improve working conditions, thereby ensuring their reputation and support is secure (Cote & Harris, 2023A). By examining case studies such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, The Quiet Man, and Cyberpunk 2077, this paper illustrates how the drawbacks of crunch can often outweigh the benefits. For instance, rushed development can lead to major financial losses, negative consumer reception, and damage to company reputation. In some cases, studios have achieved high-frequency, high-profit releases even at the cost of employee wellbeing, raising concerns about the ethical sustainability of such models. There are games that have succeeded despite a rushed development cycle, and the issue unfortunately mainly only becomes more noticed by audiences when poor working conditions lead to the failure of a product that raised excitement and expectations.

My goal for this research was to effectively emphasize the need for greater awareness and action on this topic so that the issue of development crunch is more widely discussed throughout the gaming industry. In addition, I tried to develop a practical prototype with a team to learn more about the challenges that come with developing games, and the process taught me that effective organization and the willingness to sacrifice either time or game content is important. It’s also evident that the frequent practice of crunch can have harmful effects on employees, the products they are working on, as well as the potential creativity and artistic messages of those products. I believe contributing towards the dialogue regarding the issue of development crunch, as well as its overall impact on the gaming industry, can lead to necessary changes. By promoting awareness and advocating for changes that can allow for more ethical and sustainable practices in the field of game development, it may be possible for a future to exist in which games are created with passion without sacrificing the well-being of the people who make them.

Acknowledgements

I would like to first extend my appreciation to Dr. Bruno De Paula and Dr. Christopher Rhodes from University College London. Your work and guidance have been invaluable resources while I was developing this piece; thank you so much. I would also like to extend my thanks to Sipeng Wang, Jialiang Xu, and Pang Yunhao, who each played a contributing role towards the production of the practical prototype of Game Maker Mayhem. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the passionate industry professionals and journalists who discussed with me the topic of ethical practices in the gaming industry and how changes can be made to accommodate a more sustainable environment for games workers. Their dedication and interest towards the field of games development played a notable role in inspiring this work.

Author Biography

Shaif Hemraj is a lecturer in Games Development at the University of Westminster who has a strong interest in digital media production and game development. His work addresses an array of topics, such as creative expression in games, visual aesthetics in digital media, and the impact of artificial intelligence in the entertainment industry. Hemraj believes that creativity often plays a notable role in a game’s overall appeal and success and hopes to deepen both academic and industry understandings of how artistic choices and styles influence games.

References

Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), 2023. Microsoft/Activision: Final report. [online] GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/microsoft-slash-activision-blizzard-merger-inquiry

Cote, A.C. & Harris, B.C. (2021). ‘Weekends became something other people did’: Understanding and intervening in the habitus of video game crunch. Convergence, 27(1), 161-176.

Cote, A.C. & Harris, B.C. (2023a). Inevitable or Exploitative? A Case Study of Consumers’ Divergent Attitudes towards Video Game Crunch. Media Industries, 10(1).

Cote, A.C. & Harris, B.C. (2023b). The cruel optimism of “good crunch”: How game industry discourses perpetuate unsustainable labour practices. New Media & Society, 25(3), 609-627. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211014213

Crane, D. (2016). Interview with David Crane. Arcade Attack. Retrieved from https://www.arcadeattack.co.uk/interview-david-crane

Cyberpunk 2077. (2021). Cyberpunk 2077 — Our Commitment to Quality. Cyberpunk 2077 Official Website. Available at: https://www.cyberpunk.net/en/news/37298/our-commitment

Day, C., Ganz, M., Hornsby, D., McElhenney, R., Green, D.G., Frenkel, N. Rotenberg, M., Altman, J., Kreinik, D., & Guillemot, G. (2020-2025). Mythic Quest. 3 Arts Entertainment; Ubisoft Film & Television; Lionsgate Television.

De Lucena, D. P., & da Mota, R. R. (2017). Games as expression: On the artistic nature of games. Proceedings of SBGames 2017, 812–821.

de Peuter, G. & Dyer-Witheford, N. (2005). A Playful Multitude? Mobilising and Counter-Mobilising Immaterial Game Labour. The Fibreculture Journal. Available at: https://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-024-a-playful-multitude-mobilising-and-counter-mobilising-immaterial-game-labour/

Dring, C. (2018). How to avoid video game development crunch. GamesIndustry.biz. Available at: https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2018-10-19-how-to-avoid-video-game-development-crunch

Epic Games. (2017-2024). Fortnite. Epic Games.

Ernkvist, M. (2008). Down Many Times, but Still Playing the Game Creative Destruction and Industry Crashes in the Early Video Game Industry 1971-19861. History of Insolvency and Bankruptcy.

Francis, B. (2022). CD Projekt full-year 2021 financials marred by slow ‘Cyberpunk’ sales. Game Developer. Available at: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/cd-projekt-full-year-2021-financials-marred-by-slow-i-cyberpunk-i-sales

Gallagher, S., & Park, S. H. (2002). Innovation and competition in standard‑based industries: A historical analysis of the U.S. home video game market. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 49(1), 67–82.

Game Freak. (2017A). Pokémon Ultra Moon. Nintendo; The Pokémon Company.

Game Freak. (2017B). Pokémon Ultra Sun. Nintendo; The Pokémon Company.

Game Freak. (2022A). Pokémon Scarlet. Nintendo; The Pokémon Company.

Game Freak. (2022B). Pokémon Violet. Nintendo; The Pokémon Company.

GDC. (2019). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2019. Game Developers Conference. https://reg.gdconf.com/gdc-state-of-game-industry-2019

Gilbert, B. (2019). Video game development problems explained: Crunch culture at EA, Rockstar, Epic, and more. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/video-game-development-problems-crunch-culture-ea-rockstar-epic-explained-2019-5

Gordon, R. (2018). The Quiet Man Review. Screenrant. https://screenrant.com/the-quiet-man-review/

Henry, J. (2019). 15 Worst Video Games Of 2018, According To Metacritic. Gamerant. Available at: https://gamerant.com/worst-games-2018-metacritic/

Hesmondhalgh, D., & Baker, S. (2011). Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. Routledge.

Hoffman, E. (2004). EA: The Human Story. LiveJournal. https://ea-spouse.livejournal.com/274.html

Human Head Studios. (2018, November 1). The Quiet Man. PC: Square Enix.

Insomniac Games. (2023). Marvel’s Spider-Man 2. Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Josefsson, I. (2017). Navigating Creative Work. Doctoral Thesis. University of Bath.

Judge, M., Berg, A., Altschuler, J., Krinsky, D., Rotenberg, M., Lassally, T., Tarver, C., Kleverweis, J., Babbit, J., & Morton, L. (Executive Producers). (2014-2019). Silicon Valley [TV series]. Altschuler Krinsky Works; Alec Berg Inc.; 3 Arts Entertainment; HBO Entertainment.

Kennedy, V. (2023). Becoming Hailey: Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, Actress Natasha Ofili, and Insomniac on Deaf Representation and More. Eurogamer.

Kent, G. (2017). Edmonton’s BioWare uses upcoming release of Mass Effect: Andromeda to push for industry tax credits. Edmonton Journal. https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/edmontons-bioware-uses-upcoming-release-of-mass-effect-andromeda-to-push-for-industry-tax-credits

Keogh, B. (2023). The videogame industry does not exist: Why we should think beyond commercial game production. MIT Press.

Klepek, P. (2017). What went wrong with Mass Effect: Andromeda? Waypoint. https://www.vice.com/en/article/9kqq97/what-went-wrong-with-mass-effect-andromeda

Kushner, D. (2012). Jacked: The Outlaw Story of Grand Theft Auto. John Wiley & Sons.

Legault, M.-J., & Weststar, J. (2015). Working time among video game developers: Trends over 2004–2014. Management and Organizational Studies. Retrieved from https://r-libre.teluq.ca/697/1/WorkingTimeSummaryReport-Final-15.pdf

Linton, G. (2022). An introduction to failure. IEEE Potentials, 41(4), pp. 8-10.

MacDonald, K. (2021). Video game internships can be exploitative, but they don’t have to be. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2021/01/05/video-game-internships/

Marks, T. (2024). Cyberpunk 2077 review. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/cyberpunk-2077-review

McCarty, J. (2019). Crunch culture consequences. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/crunch-culture-consequences

Mertens, J. (2022). Broken Games and the Perpetual Update Culture: Revising Failure With Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed Unity. Games and Culture, 17(1), 70-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211017044

Metacritic. (2017). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. https://www.metacritic.com/game/switch/the-legend-of-zelda-breath-of-the-wild

Metacritic. (2023). The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. https://www.metacritic.com/game/switch/the-legend-of-zelda-tears-of-the-kingdom

National Museum of American History. (2014). Landfill: Smithsonian Collections: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial Atari 2600 Game. American History. Available at: https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/landfill-smithsonian-collections-et-extra-terrestrial-atari-2600-game

Nesterenko, O. (2020). Supergiant employees required to take at least 20 days off per year. Game World Observer. https://gameworldobserver.com/2020/12/07/supergiant-employees-required-take-least-20-days-off-per-year

Nieborg, D. B. (2015). Crushing Candy: The Free-to-Play Game in Its Connective Commodity Form. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1-12.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2056305115621932

Nightingale, E. (2023). Majora’s Mask’s most infamous line is actually all about crunch. Eurogamer. https://www.eurogamer.net/majoras-masks-most-infamous-line-is-actually-all-about-crunch

Nintendo Dream. (2000, July). [Interview with Shigeru Miyamoto on Majora’s Mask development]. Nintendo Dream Magazine Supplement. (In Japanese).

Nintendo EAD. (1998). The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Nintendo.

Nintendo EAD. (2000). The Legend of Zela: Majora’s Mask. Nintendo.

Nintendo EAD. (2017, March 3). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Nintendo Switch: Nintendo.

Nintendo EAD. (2023, May 12). The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. Nintendo Switch: Nintendo.

Nintendo. (2015). Iwata Asks: Majora’s Mask 3D [Interview]. Available at: https://iwataasks.nintendo.com/interviews/3ds/majoras-mask-3d/0/0/

Nintendo. (2023). Financial Results Briefing for Fiscal Year Ended March 2023. https://www.nintendo.co.jp/ir/en/finance/software/index.html

Nintendo. (2025). Nintendo financial results briefing, fiscal year ending March 2025. https://www.nintendo.co.jp/ir/en/finance/hard_soft/index.html

Nomada Studio. (2018, December 13). Gris. PC: Devolver Digital.

Notis, A. (2021). Naughty Dog’s bosses still don’t get it. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/naughty-dog-s-bosses-still-don-t-get-it-1847583766

Nowicki, Michał. (2021). “Is it time for a crisis of trust? Case of CD PROJEKT RED game development studio and their ‘masterpiece’–Cyberpunk 2077 premiere.” Proceedings of the 38th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA). ISBN: 978-0-9998551-7-1, ISSN: 2767-9640.

O’Donnell, C. (2014). Developer’s Dilemma. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Otero, J. (2017). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild Review. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/2017/03/02/the-legend-of-zelda-breath-of-the-wild-review

Parker, F. (2012). An art world for artgames. Loading…, 7(11). https://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/119

Peticca-Harris, A., Weststar, J., & McKenna, S. (2015). The perils of project-based work: Attempting resistance to extreme work practices in video game development. Organization, 22(4), 570-587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572509

Petite, S. (2018). ‘You’re better off setting 15 bucks ablaze than playing The Quiet Man’. Digital Trends. Available at: https://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/the-quiet-man-game-review/

Playdead. (2010, July 21). Limbo. PC: Playdead.

Politowski, C., Petrillo, F., Ullmann, G. C., & Guéhéneuc, Y.-G. (2021). Game industry problems: An extensive analysis of the gray literature. Information and Software Technology, 136, 106538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2021.106538

Radić, V. (2020). The Highest-Selling Legend Of Zelda Games Ranked (& How Much They Sold). Gamerant. https://gamerant.com/highest-selling-legend-of-zelda-games-ranked-by-amount-sold-phantom-hourglass-majoras-mask-wind-waker/

Richard, I. (2023). Minecraft sells 300 million copies, still the best-selling game of all time. TechTimes. https://www.techtimes.com/articles/297564/20231016/minecraft-sells-300-million-copies-still-best-selling-game-time.html

Rockstar Games. (2018). Red Dead Redemption 2. Rockstar Games.

Rockstar North. (2002). Grand Theft Auto: Vice City. Rockstar Games.

Rodrigues, M.A.F, de Oliveira, T.R.C., de Figueiredo, D.L., Maia Neto, E.O., Akao, A.A.A., & de Lima, G.H.M. (2022). An Interactive Story Decision-Making Game for Mental Health Awareness. In 2022 IEEE 10th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), pp. 1-8. doi: 10.1109/SEGAH54908.2022.9978592.

Ruberg, B. (2020). Empathy and its alternatives: Deconstructing the rhetoric of “empathy” in video games. Communication, Culture & Critique, 13(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz044

Ruffino, P. (2016). Burying ET the Extra-Terrestrial: Undoing Game Archaeology. In First Joint International Conference of DiGRA and FDG. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/818/818

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press.

Schreier, J. (2018). Inside Rockstar Games’ culture of crunch. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/inside-rockstar-games-culture-of-crunch-1829936466

Schreier, J. (2019). How BioWare’s Anthem went wrong. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/how-biowares-anthem-went-wrong-1833731964

Shea, C. (2022). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild – Five-year development anniversary: Fascinating facts. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/zelda-breath-of-the-wild-development-five-year-anniversary-fascinating-facts

Siuda, P., Reguła, D., Majewski, J., & Kwapiszewska, A. (2023). Broken Promises Marketing. Relations, Communication Strategies, and Ethics of Video Game Journalists and Developers: The Case of Cyberpunk 2077. Games and Culture, 19(5), 650-669. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231173479 (Original work published 2024)

Skains, R. (2018). Media Practice and Education. Tandfonline. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682753.2017.1362175

Sotamaa, O., Švelch, J. & Keogh, B. (2021). Hobbyist Game Making Between Self-Exploitation and Self-Emancipation. In: O. Sotamaa & J. Švelch (Eds.), Game Production Studies. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 29.

Square Enix Business & Division 1. (2020). Final Fantasy VII Remake. Square Enix.

Square Enix Product & Development Division 1. (2005). Kingdom Hearts II. Square Enix.

Stalberg, M. (2023). Zelda: Majora’s Mask’s director didn’t have time to play the game start to finish before release. SVG. https://www.svg.com/1162026/zelda-majoras-masks-director-didnt-have-time-to-play-the-game-start-to-finish-before-release/

Sterling, J. (2018). The Quiet Man – The Jimquisition [Video file]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hugh_V_VWrQ&ab_channel=JimSterling

Sun, J. & Zhou, Z. (2022). Impact of the game Cyberpunk 2077 on cyberpunk culture. In 2021 International Conference on Education, Language and Art (ICELA 2021) (pp. 640-643). Atlantis Press.

Supergiant Games. (2020). Hades. Supergiant Games.

Tassi, P. (2022). Pokémon Scarlet and Violet’s 10 Million Copies Sold In Three Days Breaks Every Nintendo Record. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2022/11/24/pokemon-scarlet-and-violets-10-million-copies-sold-in-three-days-breaks-every-nintendo-record/?sh=130564b36f38

Tassi, P. (2023). CDPR can’t rewrite history about the ‘Cyberpunk 2077’ launch. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2023/06/28/cdpr-cant-rewrite-history-about-the-cyberpunk-2077-launch/?sh=7f17798e3f3c

Thier, D. (2012). EA responds to being voted the most evil company in America. Forbes. Consumerist. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidthier/2012/04/04/ea-responds-to-being-voted-the-most-evil-company-in-america/

Thier, D. (2020). CD Projekt Red developers are getting death threats after ‘Cyberpunk 2077’ delay. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidthier/2020/10/28/cd-projekt-red-developers-are-getting-death-threats-after-cyberpunk-2077-delay/

Tomlinson, C. & Anderson-Coto, M.J. (2020). Sowing seeds of distrust: Video game player perceptions of companies in online forums. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2020i0.11350

Treyarch & n-Space. (2008). Call of Duty: World at War. Activision.

Wallick, A. (2016). No wrong way to make a game [Conference presentation]. Game Developers Conference (GDC), San Francisco, CA. https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1023384/No-Wrong-Way-to-Make

Weststar, J. (2015). Understanding video game developers as an occupational community. Information, Communication & Society, 18(10), 1238–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1036094

Weststar, J., & Legault, M.-J. (2018). Women’s experiences on the path to a career in game development. In K. Gray, G. Voorhees, & E. Vossen (Eds.), Feminism in Play (pp. 105–123). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90539-6_7

Weststar, J., Kwan, E., & Kumar, S. (2019). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2019: Summary Report. International Game Developers Association.

https://s3-us-east-2.amazonaws.com/igda-website/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/29093706/IGDA-DSS-2019_Summary-Report_Nov-20-2019.pdf